Text and Photos by Henrylito D. Tacio

Additional Photo from DOST

Unlike those of politicians, movie stars, and basketball players, the name Ramon C. Barba may not ring a familiar bell. But among scientists, he is the man behind the year-round availability of fresh mangoes.

Last October 10, the scientist known for his distinguished achievements in the field of plant physiology passed away at the age of 82.

“His pioneering work on the induction of flowering and fruiting mango resulted in the change from seasonal supply of fresh fruits to year-round availability of abundant fresh mangoes,” the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) said in a statement.

The mango induction technology was patented not only in the Philippines but also in other countries like the United States, England, Australia, and New Zealand. “He did not collect any royalty from the patent so that ordinary farmers can freely use the technology,” the DOST said.

As a result of such generosity, many mango-producing countries in Latin America, Africa, Asia, and Australia have adopted the technology for their mango production.

Before 1974, mangoes were available for a short period of time only, specifically during the summer months. “Despite the superior taste of mangoes, and despite being around since six centuries ago, they remained virtually a commercially neglected fruit that raised little revenue,” observed Dr. Barba. “This lowly status was largely because mango has unreliable fruiting habits.”

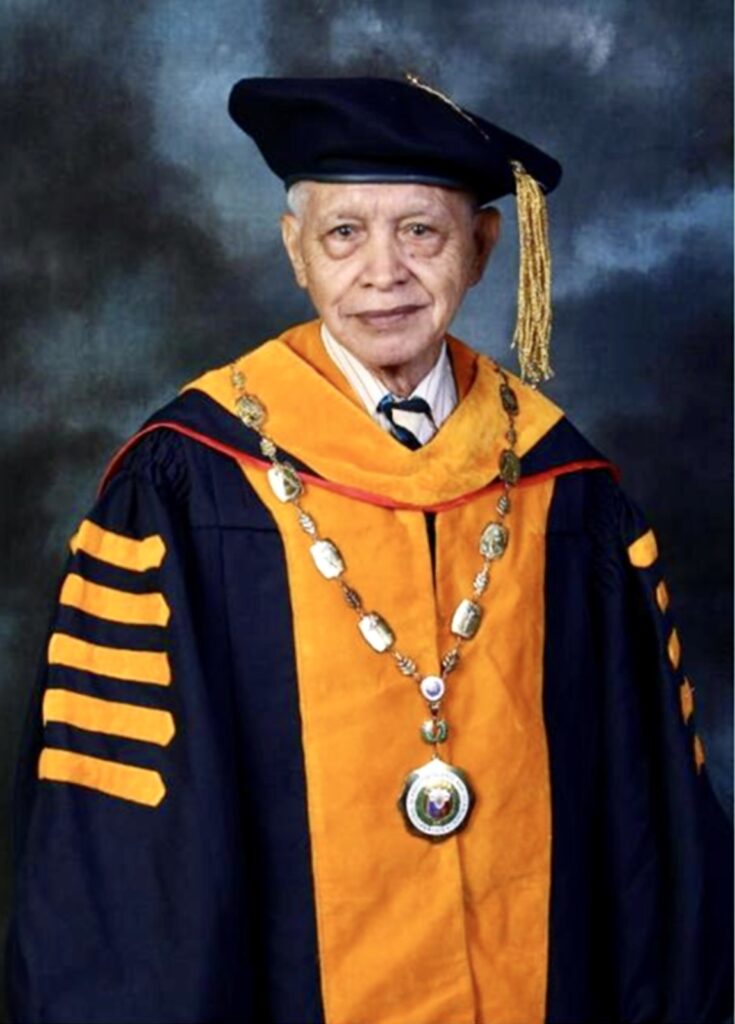

Dr Ramon C Barba

Mangoes for sale

In those years, the fruit habits of mangoes were seasonal, biennial, and erratic. “If (mangoes) bear fruit one year, they may not do so the next year,” said Dr. Barba, whose academic background was agronomy and fruit production. “Usually, mango trees bear fruit for only one month in a year. Yield may vary from year to year, from tree to tree in a grove, and even from branch to branch in a tree.”

These unreliable fruit habits of mangoes were the reason why investors were not so keen on engaging in mango production. “A requirement for economic stability of any fruit industry is regular production, which means active control of flowering and fruiting,” Dr. Barba recalled in his Dr. D.L. Umali Lecture, “Revolutionizing Agricultural Science and Farming Technology: Chemical Flower Induction of Mango.”

“Controlled flowering,” he continued, “is ideal to produce out of season crop, to increase production during the normal flowering season, or to offset its biennial, erratic, and sparse fruit bearing habits.”

To solve the problem, farmers at that time resorted to the ancient and unique practice of smudging. It is the process of building a smoky fire beneath the tree and then allowing the dense smoke to pass through the foliage continuously for 20 days. This process helped advance the bearing of fruit in about a month.

“Smudging is cumbersome, slow, costly, and unreliable,” Dr. Barba remarked of the folk practice. “Overall, smudging as a technology did not propel the mango fruit crop to commercial prominence.”

However, he observed that the ethylene in smoke produces the flowering effect; since ethylene is a gas, the mango tree would then have to be covered in order to get the best results from smudging. This gave him the idea of believing there was a better, more efficient, and economical way than smudging to induce flowering in mangoes.

That was what he did. As Assistant Professor at the Fruit Crops Section Department of Agronomy at the University of the Philippines College of Agriculture, he considered the possible use of Ethrel on mango.

But the research was already conducted on it. When he reviewed the result of the study, he found out that using high concentrations of Ethrel in mango causes defoliation. In low concentration, however, the success rate of flower induction was reduced.

When his request to further conduct experiments on it, he was turned down. So, he decided to conduct private experiments at the Quimara Farms in San Jose del Monte in Bulacan, where he served as a farm consultant. He was asked to rehabilitate the 500 mango trees planted, which were ten years old, not over 15 feet high, and had not yet attained the flowering stage.

“(The mango trees) appeared stunted and with no sign of flowering at an age when flowering should have started,” he recalled. “The owners allowed me free use of their farm for experimentation.”

Dr. Barba tried some chemicals until he settled for potassium nitrate (KNO3), which, without his knowledge, was already used as a direct agent to induce the flowering of any plant.

“I found out that KNO3 at 1% aqueous solution was effective as a spray to induce flowering in mango,” he recalled. “Lower concentrations were not as effective, while higher concentrations were wasteful and may injure the shoots. Bulging of normal shoots was observed after one week, and flowers appeared during the second week.”

He was ecstatic with the result. “In early January 1970, I sprayed one hundred trees with the same solution used in the first experiment I conducted barely two weeks earlier in order to verify the initial results,” he said. “I dissolved one kilogram of KNO3 in 100 liters of water and sprayed the solution as a drenching spray on the mango trees. In one week. Buds began to form; in two weeks, the buds were developing into flowers; and after four months, fruits reached maturity and were ready for harvesting.”

It was just a matter of time that mango production would become a money-making venture. “Mango is now on its way to becoming a major tropical and subtropical high-value fruit commodity,” Dr. Barba predicted. “This would not have been conceivable if the KNO3 flower induction technology was not in place to provide a regular and steady supply of mango for the local and international market.”

When the technology was made public in 1974, it was held as a breakthrough. In A Guide to Mangoes in Florida, author R.J. Campbell noted: “Sometimes ago, researchers discovered that they could induce good mango flowering in areas where it normally was poor by spraying the leaves with a solution of potassium nitrate. This discovery stimulated investigators in many countries on flower induction of mango… Control of flowering is a topic of great interest and an area receiving considerable research attention throughout the world.”

In 1978, the prestigious Reader’s Digest also hailed the discovery: “One of the pioneers is the Philippines… Scientists at the Los Baños College of Agriculture have found that potassium nitrate sprayed in mangoes at 1 percent concentration induces the trees to flower early and profusely… Mango, until recently, was for most an exotic name in travel books. Now, the mango is enjoyed all over the world, and is likely to become the king of tropical fruit.”

Dr. Barba’s discovery went unnoticed. In 2008, the Switzerland-based World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) recognized the mango flower induction technology through a short documentary film that promotes intellectual property. It was the first time that a country from Asia and the Pacific Region was included in the WIPO documentaries.

In 2014, he was named national scientist “for his distinguished achievements in the field of plant physiology, focusing on induction of flowering of mango and on micropropagation of important crop species that have earned him national and international accolades.”

In 2011, he was given the D.L. Umali Award. The citation reads in part: “As a scientist, Dr. Barba’s philosophy hinges on the continuous search for new frontiers. He uses his imagination to discover a possible new direction, and to take the bold and untried steps to discovery by relying on the rich store of knowledge that has come his way.”

Although mango is the country’s fruit icon, it is not endemic in the Philippines. History records showed that mangoes originated from the Myanmar region, where it was known to have been cultivated 4,000 years ago. Buddhist monks took mango to Malaya and eastern Asia in the 5th century B.C.

Later in the 18th century, Portuguese explorers would introduce mango in Brazil. From there, mango cultivation would reach Florida, United States in 1833 and eventually in Africa and in other lowland tropical and sub-tropical areas. Today, there are about 83 mango-producing countries in the world.

When it comes to mango, Philippine mangoes are number one. In fact, former Agriculture Secretary Leonardo Q. Montemayor said the variety has found its way in the Guinness Book of World Records as “the sweetest of its kind in the world.”