Text by Henrylito D. Tacio

Photos courtesy of DOST

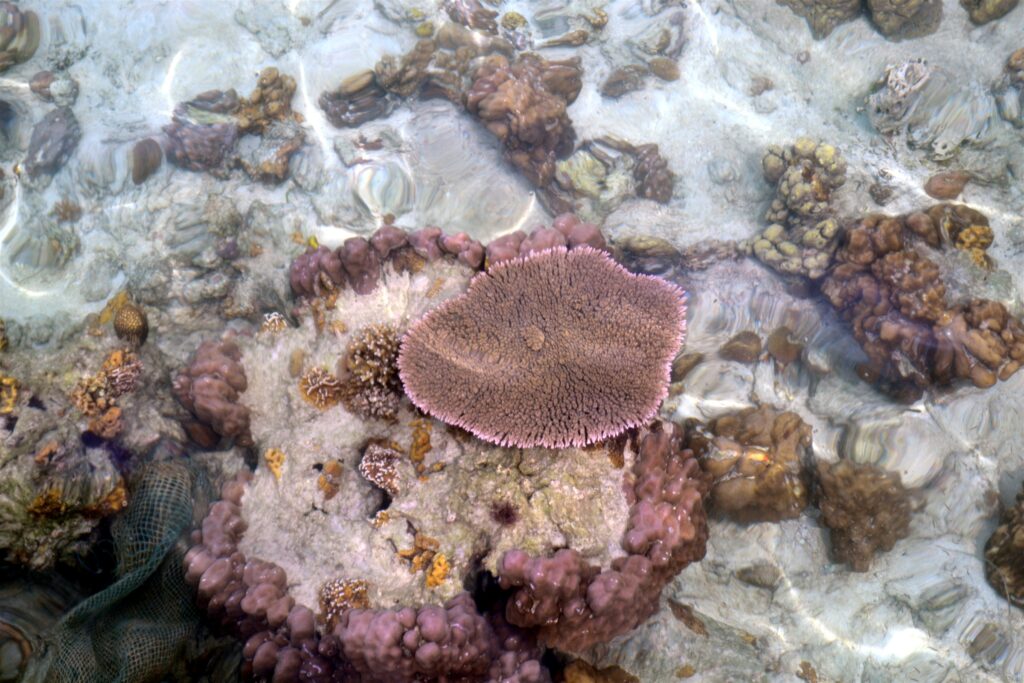

Marinduque is an island province located in Southwestern Tagalog Region or Mimaropa (Mindoro, Marinduque, Romblon, and Palawan). Some parts of the Verde Island Passage, the center of the center of the world’s marine biodiversity and a protected marine area, are within the Marinduque’s provincial waters.

In 2018, the regional office of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) initiated the assessment of coral reef areas in Marinduque through the adoption of the automated rapid reef assessment system (ARRAS) that successfully generated a comprehensive report and maps of the coral reef and seagrasses. ARRAS is a program for coral reef monitoring developed by the University of the Philippines-Diliman and funded by the DOST.

About ten coral sites along the main coastline and along the Tres Reyes Islands were surveyed. Of the sites assessed for coral cover, four were in “fair condition” (25-49% hard coral cover), and six were in “poor condition” (0-24% hard coral cover).

“Hard corals provide the reef structure that provides habitat to the rest of the organisms on the reef,” the study said.

To rejuvenate marine life in the waters of the province, a coral restoration project was launched by DOST in collaboration with the provincial government office, the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR), local government units (LGUs), and local fishermen groups.

Together, they have deployed coral transplantation technology off the coast of Buenavista and in Torrijos in what was described as “the first large-scale restoration effort” of the Mimaropa region.

Coral reef restoration

Coral reefs not in good condition

The technology being employed was the one developed by the University of San Carlos (USC) under the Filipinnovation on Coral Reef Restoration Program of the Philippine Council for Agriculture, Aquatic and Natural Resources Research and Development (PCAARRD).

Started in 2012, the Filipinnovation-initiated program seeks to roll out coral transplantation using asexually reproduced corals to improve the productivity of coral resources for sustainable fisheries.

DOST, in a news release, explained that corals asexual reproduction technology for reef restoration involves the collected of dislodged live coral fragments or “corals of opportunity” (COPs) and attaching them to coral nursery unit (CNUs) for quick recovery and regeneration to increase survival rates upon transplantation in degraded coral reef sites.

According to a press release, the CNU design and the coral transplantation technique, which uses marine epoxy clay, nails, and cable tie, are outputs of the PCAARRD-funded Filipinnovation program.

The technique has been pilot-tested in major tourism and diving sites in the country, including Batangas, Bohol, and Boracay.

In Marinduque, ten CNUs were established in the Marine Protected Areas of Tungib-Lipata in Buenavista last June 10-11 and another 10 CNUs in Poctoy, Torrijos on June 22-23. CNUs are set up 25 feet underwater, and each is designed to hold 500 COPs per batch several times a year.

By the end of July 2021, the technology will be deployed in four other municipalities of Marinduque: Boac, Gasan, Mogpog, and Santa Cruz.

The Philippines is home to over 400 local species of corals, which is more than what is found in the famous Great Barrier Reef of Australia. Unfortunately, most of these species are now gone, and others are facing extinction.

“Nowhere else in the world are coral reefs abused as much as the reefs in the Philippines,” deplores Don E. McAllister of the Ocean Voice International.

The decline is thought to be due primarily to destructive human activities. “Many areas are in really bad shape due largely to unwise coastal land use, deforestation and the increasing number of fishermen resorting to destructive fishing methods,” said marine biologist Porfirio M. Alino of the University of the Philippines Marine Science Institute (MSI).

Destructive fishing methods – ranging from dynamite blasts to cyanide poisons – are destroying vast areas of the reef. Fishermen blast reefs with dynamite to stun the fish. When fish float to the surface, fishers scoop up large quantities at once.

Another equally destructive fishing method is the “muro-ami,” a drive-in net used for fishing in coral reefs. While he admitted that “muro-ami” is effective fishing gear, Dr. Rafael D. Guerrero III cited some disadvantages.

Coral transplanting

CNU

“The problems related to “muro-ami” fishing are its employment of minors (young boys) for fishing, their exposure to health hazards (like the “bends” or narcosis) and the destruction of coral reefs because of the weighted scarelines,” explained Dr. Guerrero, former executive director of Philippine Council for Marine and Aquatic Resources Research and Development.

Coral mining has also depleted the country’s reefs. In fact, an estimated 1.5 million kilograms of corals are harvested annually as part of the international trade in reef products.

Also contributing to the destruction of coral reefs in the Philippines is sedimentation from soil erosion as a result of deforestation in the uplands. “Sedimentation of waters in reef areas is the number one cause of damage,” said Dr. Edgardo G. Gomez, former MSI director. “This happens when rain water washes off sediment or silt from eroded land and carries it to the sea.”

Other causes of the deterioration of coral reefs in the country: the quarrying of coral reefs for construction purposes; pollution from industry, mining, and municipalities; and coastal population growth.

Aside from human activities, natural causes of destruction among coral reefs also occur. These include extremely low tide, high temperature of surface water, predation, and the mechanical action of currents and waves.

Extremely low tides usually expose corals to sunlight and to freshwater runoff, both of which are said to be lethal over several hours of exposure.

High temperature of surface water is exacerbated by abnormal low tides, which leave shallow reefs exposed to sunlight, rainfall, and freshwater flowing.

Then, there’s coral bleaching. This occurs when corals turn chalky white and begin to die. Coral bleaching happens when corals are under stress because of extreme sea temperatures or pollution. Corals evict their algal tenants and turn white as a result, explains Worldwatch Institute’s, John C. Ryan.

As early as the 1970s, the East-West Center in Hawaii reported that more than half of the country’s reefs were “in advanced states of destruction.” It added that only about 25% were considered to be “in good condition” while only 5% were “in excellent condition.”

Though several laws were passed, the deterioration continues unabated. For instance, a survey conducted in 1991-1992 by the Regional Fishermen’s Training Center in Panabo City at Sarangani Bay and Davao Gulf had shown that most of the shallow or inshore coral reefs “were totally damaged because they are exposed to greater pressure.”

Another study, done in the early 2000s by researchers from the Mindanao State University’s School of Marine Fisheries and Technology, showed dead corals accounted for 50% of the town’s coastline in Naawan, Misamis Oriental.

This is bad news for Filipinos whose main source of protein is fish. Touted to be “the rainforests of the ocean,” coral reefs are one of the greatest natural treasures. “A single reef may contain 3,000 species of corals, fish, and shellfish,” says Dr. Miguel D. Fortes, a marine biologist, and the first Filipino to receive the International Biwako Prize for Ecology.

An estimated 10% to 15% of the total fisheries in the Philippines come from coral reefs. About 80% to 90% of the income of small island communities come from fisheries. “Coral reef fish yields range from 20-25 metric tons per square kilometer per year for healthy reefs,” says Dr. Angel C. Alcala, the former environment secretary.

“Wild fish are the world’s most cost-efficient protein source,” points out Atty. Gloria Estenzo Ramos, head of Oceana Philippines. “They are renewable, low-carbon, and much cheaper to produce than chicken, pork, or beef.”

But as coral reefs continue to deteriorate, fish and other marine life cannot be as productive as they were before. “This will have a domino effect,” the International Marinelife Alliance-Philippines warned. “Fishermen will have fewer catches and lower income and there will be less fish and marine products for everyone.”

“We are running out of fish and running out of time. For a country known for its marine biodiversity, there are very few fish left to catch,” deplored Vince Cinches, oceans and political campaigner for Greenpeace Southeast Asia.