By Henrylito D. Tacio

Photos courtesy of Gregory C. Ira

Dr. Lourdes Cruz was among the more than 1,000 nominees worldwide for the award given annually to women scientists from five different regions of the world for their outstanding scientific contributions and commitment. Fortunately, she was chosen by a jury composed of 18 eminent members of the scientific community headed by the 1999 recipient of the Nobel Prize in medicine, Dr. Gunter Blobel.

Dr. Cruz was given the 2008 L’Oreal-Unesco Award for Women in Science “for her pioneering research on the venomous toxins of the cone snail, called conotoxin, which can produce a medication that is more powerful than morphine and can serve as powerful tools to study brain function.”

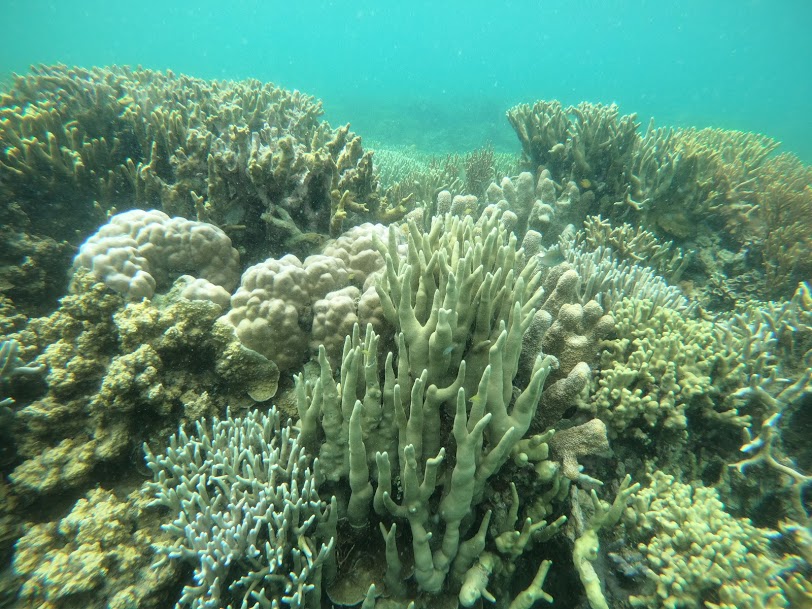

Conotoxin is just one of the chemicals found from the species inhabiting the coastal waters. Unknowingly, the ecologically-fragile coral reefs hold considerable untapped potential in medical science. So much that the US State Department said that half the potential pharmaceuticals being explored today come from the oceans, many from coral reef ecosystems.

“The sky’s the limit,” Dr. Deborah Gochfeld, a senior research scientist at the National Center for Natural Products Research of the University of Mississippi, told this author. “The oceans have a much broader diversity of chemical structures than are found in plants – which include uses for cancer, heart disease, and infections, among others – so it is likely that marine animals will include all of these options and more.”

Dr. William Fenical, director for marine biotechnology and biomedicine at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, California, echoes the same idea. “Marine resources could be the major source of drugs in the coming years,” he pointed out.

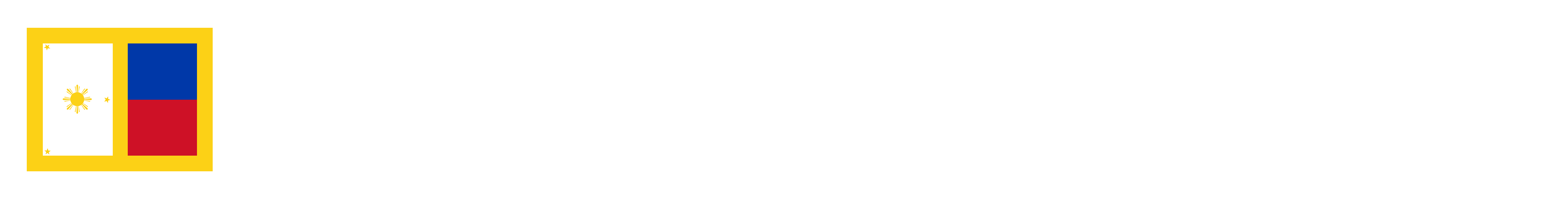

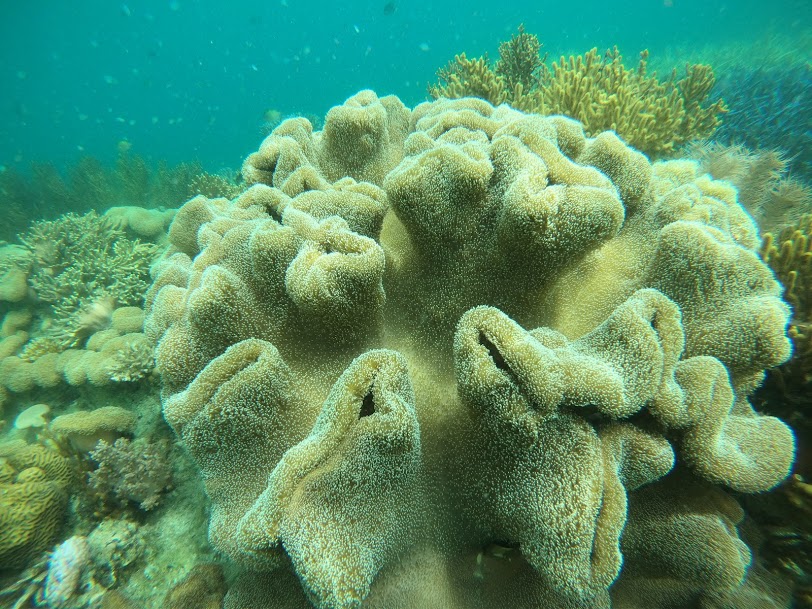

Most of these marine resources thrive in coral reefs. “Many coral reef species produce chemicals like histamines and antibiotics used in medicine and science,” reports The Nature Conservancy, an organization whose mission is to preserve plants, animals, and natural communities by protecting the lands and waters needed for their survival.

“Coral reefs are sometimes considered the medicine cabinets of the 21st century,” says the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). “Coral reef plants and animals are important sources of new medicines being developed to treat cancer, arthritis, human bacterial infections, Alzheimer’s disease, heart disease, viruses, and other diseases.

“Some coral reef organisms produce powerful chemicals to fend off attackers, and scientists continue to research the medicinal potential of these substances,” it adds.

Touted to be the rainforests of the sea, Coral reefs are one of the most productive and biologically rich ecosystems on earth. They extend across about 250,000 square kilometers of the ocean – less than one-tenth of one percent of the marine environment – yet they may be home to 25 percent of all known marine species.

“About 4,000 coral reef-associated fish species and 800 species of reef-building corals have been described to date, though these numbers are dwarfed by the great diversity of other marine species associated with coral reefs, including sponges, urchins, crustaceans, mollusks, and many more,” Reefs at Risk Revisited in the Coral Triangle reported.

For centuries, coastal communities have used reef plants and animals for their medicinal properties. In the Philippines, for instance, giant clams are eaten as a malaria treatment.

“Unique medicinal properties of coral reef organisms were recognized by Eastern cultures as early as the 14th century, and some species continue to be in high demand for traditional medicines,” observes Dr. Andrew Bruckner, a coral reef ecologist in the US National Marine Fisheries Service’s Office of Protected Resources in Silver Spring, Maryland.

In China and Taiwan, tonics and medicines derived from seahorse extracts are used to treat a wide range of ailments, including sexual disorders, respiratory and circulatory problems, kidney and liver diseases, throat infections, skin ailments, and pain.

In Japan’s reefs – one of the most studied coral coasts in the world – there is a chemical called kainic acid, which is used as a diagnostic chemical to investigate Huntington’s chorea, a rare but fatal disease of the nervous system. Sea whips, a type of soft coral found throughout the Caribbean, may hold the key to promising new painkillers.

Other coral chemicals have proved useful in research on arthritis and asthma. In Australia, researchers have developed a sun cream for a coral chemical that contains a natural “factor 50” sunblock.

In addition, the porous limestone skeleton of coral is now being tested as bone grafts in humans. “If used properly, the reefs of the entire world can better serve humans with medicine rather than with food,” some researchers claim.

In an article that appeared in Reef Research, Dr. Patrick Colin, a marine biologist, clearly described the hopes that had led him to spend the 1990s collecting marine samples in the Pacific for the US National Cancer Institute (NCI).

“Over the years, the NCI has been screening terrestrial plants and marine organisms worldwide for bioactivity against cancer and Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS), and has come up with a number of hot prospects, a number of which are in clinical trials,” Dr. Colin wrote.

Already, the NCI has been screening each year about 1,000 species of oceanic invertebrates and plants, including sea slugs, sea squirts, sponges, and several other denizens of coral gardens.

“The marine environment became a focus of natural products drug discovery research because of its relatively unexplored biodiversity,” says the book, From Monsoons to Microbes.

According to the book, marine sponges are among the most prolific sources of diverse chemical compounds with therapeutic potential. More than 5,000 chemical compounds derived from marine organisms and more than 30 percent have so far been isolated from sponges.

Chemicals with therapeutic potential can also be extracted from bryozoans, ascidians, mollusks, cnidarians, and algae. Several strains of phytoplankton have been discovered to be exhibiting antibacterial and antifungal properties.

Since the mid-1970s, private and government-funded institutions from the United States and other industrialized countries have devoted varying levels of effort to discovering marine-derived pharmaceuticals.

Meanwhile, the use of corals in bone grafts is spreading rapidly—pieces of coral set into a fracture act as a scaffold around which the healing can occur. The implant eventually disappears, absorbed by the new growth of bone. Rates of rejection are much lower than with artificial grafting materials.