By Henrylito D. Tacio

Photos courtesy of WHO

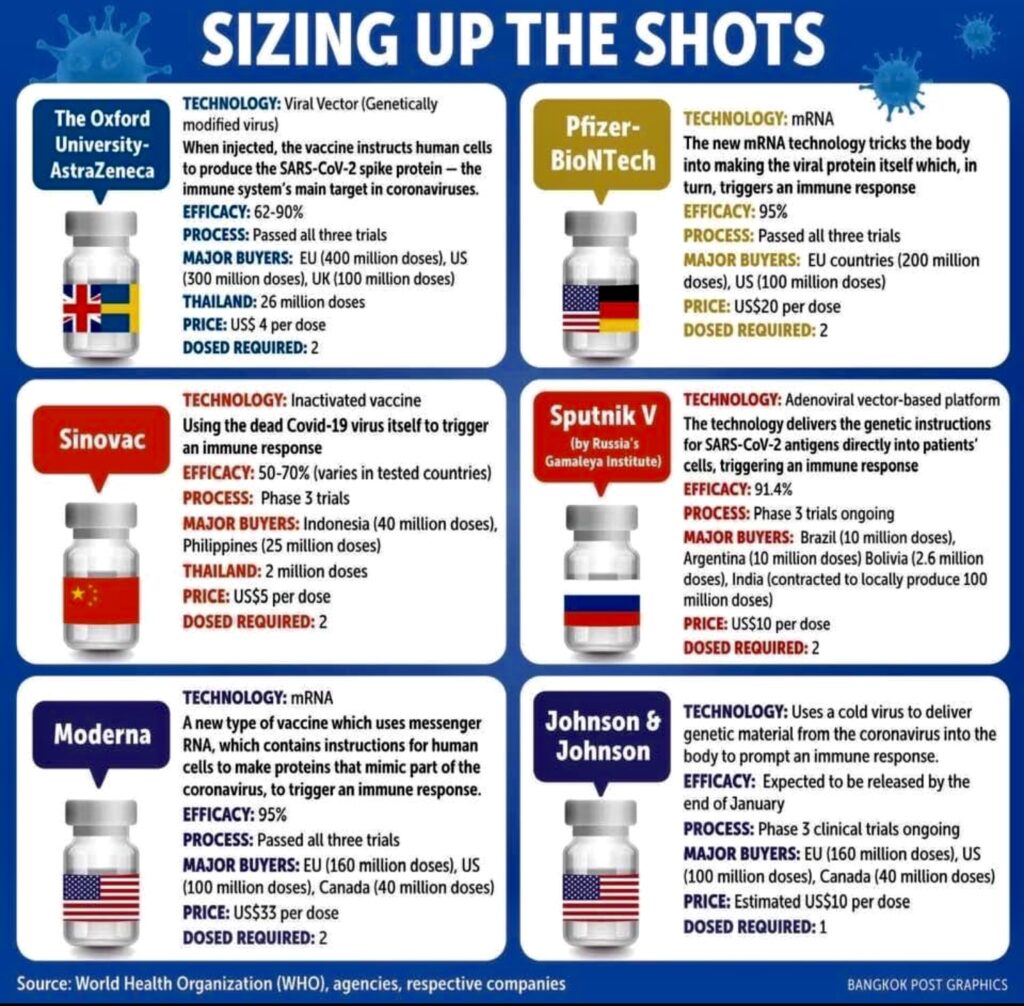

Infographic from Bangkok Post

If we want to return to the time when we don’t wear face masks and face shields, hug each other, and talk with freedom and laughter, then the world’s population needs to be immune to Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the microorganism that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Although that might be unthinkable and may not happen immediately, we can return to “normal” only if most of the world’s population are already vaccinated. “Though vaccination is a choice, don’t forget that vaccines have been around a long time and have saved more lives than any other medicine,” Dr. Tracy Hussell, professor of inflammatory disease at the University of Manchester, reminds.

“One year ago, a new virus emerged and sparked a pandemic. Life-saving vaccines have been developed. What happens next is up to us,” said Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO), in his opening remarks at the 148th session of the executive board last January 19.

“We have an opportunity to beat history; to write a different story; to avoid the mistakes of the HIV and H1N1 pandemics,” he added. “The development and approval of safe and effective vaccines less than a year after the emergence of a new virus is a stunning scientific achievement, and a much-needed source of hope.”

Vaccines, he pointed out, “are the shot in the arm we all need – literally and figuratively.”

Vaccination is one of the most effective practices in protecting yourself from infectious diseases as it improves your immune system. “Immunization results in an individual possessing antibodies that recognize and remember the specific infectious organism and learn to respond more strongly to a succeeding exposure,” explains Dr. Angeles Tan Alora, former president, now adviser, for Philippine Society for Microbiology and Infectious Disease.

Once vaccinated, a person can now resist the specific infection, have less chance of getting sick, or get severe or complicated disease. If the whole community has been immunized, there is a chance that the specific infectious diseases are reduced or even eradicated.

But not all people can be vaccinated; some might be allergic to the vaccine or have some health problems so much that they should not receive the vaccine. This is where herd immunity comes into the picture.

“Herd immunity refers to the condition wherein immunizing a proportion of the population is sufficient to protect the community and achieve control of the disease,” Dr. Alora explains. For instance, a house with 10 members and only the two old folks and a pregnant woman have not been immunized; then, the three are still protected since all seven have been vaccinated.

“Before COVID-19, it often took a decade or longer to develop and make a vaccine widely available to the public, although the first polio vaccine developed by Jonas Salik took only six years, and more recently, a vaccine against the Zika virus took only 6.5 months from its inception to human testing,” Dr. Hussell writes.

The reason why it takes years is because the vaccine has to undergo a preclinical phase and 4 clinical phases. However, the development of the COVID-19 vaccine was accelerated. “During the COVID-19 pandemic, institutions around the world raced to meet the demand for effective measures to combat and control the disease,” Dr. Alora notes.

The COVID-19 vaccine development process accelerated building on knowledge from the epidemic caused by two previous coronavirus strains: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS).

There are currently four categories of vaccines in clinical trials: whole virus, protein subunit, viral vector, and nucleic acid (RNA and DNA). Some try to smuggle the antigen into the body, and others use the body’s own cells to make the viral antigen.

In addition, countries like the United States and Great Britain approved specific vaccines despite the lack of the usual complete development cycle, particularly phase 4 of the clinical trial, where the vaccine is tested on a large population to ensure long term safety and efficacy. The urgency of the situation justified their action.

The Philippines does not produce a vaccine. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is the country’s regulatory authority; it has the “responsibility to ensure that these vaccines are safe and efficacious.”

Right now, 9 COVID-19 vaccines can be imported by the Philippines. These are Pfizer-BioNTech (a collaboration of US and Germany), AstraZeneca-Oxford (made in the United Kingdom), Sputnik V (Russia), Moderna (US), Janssen (Belgium-US), Sinovac and Sinopharm (both from China), Clover (China-Australia), and Novavax (US).

“Inasmuch as vaccines are imported, stored, and delivered to the place of vaccination, it is essential that transport, storage, and handling facilities and processes keep the vaccine viable and stable,” Dr. Alora explains. “The match between what is needed for these and what can and will be done is extremely important in decisions regarding which vaccines to purchase and where people should be vaccinated.”

The following vaccines require normal fridge temperature for their storage: Janssen, Sinovac, Sinopharm, Clover, and Novavax. AstraZeneca-Oxford also needs normal fridge temperature (2°C to 8°C), while Sputnik V likewise needs a dry form of normal fridge temperature. Moderna has a storage requirement of -25°C to -15°C. Pfizer-BioNTech is even lower: -70°C.

“No vaccine is absolutely and completely safe or perfectly effective,” Dr. Alora reminds. “But the risks of most vaccines are outweighed by the risks of getting the disease.”

Filipinos have four options in getting the vaccine:

- A vaccine approved by the FDA for public use.

- A vaccine approved by the FDA for clinical trials.

- From vaccines available from the black market.

- To go abroad for the vaccination.

“Whichever option you choose, be aware of the vaccine limitations,” Dr. Alora stresses and adds that before allowing yourself to be vaccinated, you need to ask yourself if the vaccination is right for you.

Among the questions, you need to answer yourself are the following:

1) Are you exposed to the disease, likely to get it, and therefore in need of protection? Chances are, if you are the average sociable Filipino, you are definitely exposed to the disease.

2) Is your immune system robust enough to mount a favorable response to the vaccine? Are you on immunosuppressive treatment, in an immunocompromised condition, or elderly? These may impair your immune system.

3) Are you presently sick, especially with a fever? If yes, vaccination is also not advised. You don’t want to confuse your immune system, and you don’t want adverse reactions to add to your discomfort.

4) Are you likely to develop an adverse reaction? Side effects are mostly transient and mild: the vaccine site’s redness and soreness are easy to tolerate. Reported serious adverse reactions are few and usually relate to allergy. If you have had previous allergic reactions to vaccination, think twice.

Now, will Dr. Alora allow herself to be vaccinated? “Certainly, once a vaccine is approved by the FDA for public use, it is available from a reliable institution, and will be administered by a competent healthcare giver,” she replies.

In the meantime, she urges the public to follow the effective public health measure to prevent the spread of the COVID-19 virus. These are: staying one meter away from others, choosing well-ventilated spaces, wearing a mask and face shield, washing hands and disinfecting, covering the nose and mouth when coughing or sneezing, and isolating the sick.