Text by Henrylito D. Tacio

Photos: Wikipedia and Mayo Clinic

In December 2019, Davao del Sur was one of the ten provinces in the Philippines to be declared as “malaria-free provinces” by the Malaria Technical Working Group of the National Malaria Control and Elimination Program (NMCEP).

Four other provinces in Mindanao made it to the list: Zamboanga Sibugay, Zamboanga del Norte, Agusan del Norte and Saranggani. The remaining provinces were Antique, Negros Oriental, Tarlac, Laguna and Quezon.

The declaration of the ten provinces has raised the number of malaria-free provinces in the country to 60 out of 81. It is on its way to being declared a malaria-free country. To achieve such status, the World Health Organization (WHO) said it should have achieved at least three consecutive years of “zero indigenous cases.”

Although Davao City is part of Davao del Sur, it has not been declared malaria-free yet. In May 2019, a news report from Sunstar Davao said: “Davao City has not yet been declared as malaria free despite not having any reported malaria cases in the last two years. If the city does not have any malaria cases reported in another three years, then that will be the time they will declare it as malaria free.”

The source of information was Engineer Antonietta Ebola, the manager of the Davao Regional Dengue Control and Prevention Program of the Department of Health (DOH).

The last time Davao City reported a malaria outbreak was in 2010. This occurred when 183 of the 645 suspected cases were tested positive for malaria in barangay Gumitan in Marilog District. Malaria was reported to be prevalent in the Paquibato district.

By 2030, the NMCEP wants to see the Philippines already a malaria-free country. “The Philippines has significantly reduced the incidence of malaria by 87% from 48,569 in 2003 to 6,120 cases in 2020, and has also reported a 98% reduction in the number of mortality due to malaria, from 162 deaths in 2003 to 3 deaths in 2020,” the DOH states.

Before that happens, however, the health department aims to reduce first the malaria incidence rate by 90% by 2022. To realize this goal, the strategies include early diagnosis and complete treatment, use of insecticide-treated nets, and indoor residual spraying of insecticide.

Between 2000 and 2019, the number of countries with fewer than 100 indigenous malaria cases increased from six to 27, according to the WHO, calling it “a strong indicator” that malaria elimination is within reach.

The UN health agency lauded those countries that have already done so, saying: “They provide inspiration for all nations that are working to stamp out this deadly disease and improve the health and livelihoods of their populations.”

Malaria amidst pandemic

The elimination of malaria was at its business-as-usual program when the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) entered into the picture in 2020. In many countries, lockdowns and restrictions on the movement of people and goods have led to delays in the delivery of insecticide-treated mosquito nets or indoor insecticide spraying campaigns.

Malaria diagnosis and treatment services were interrupted as many people were unable – or unwilling – to seek care in health facilities. Filipinos feared going to the hospitals as fever, a common symptom of malaria, is also one of the common symptoms of COVID-19.

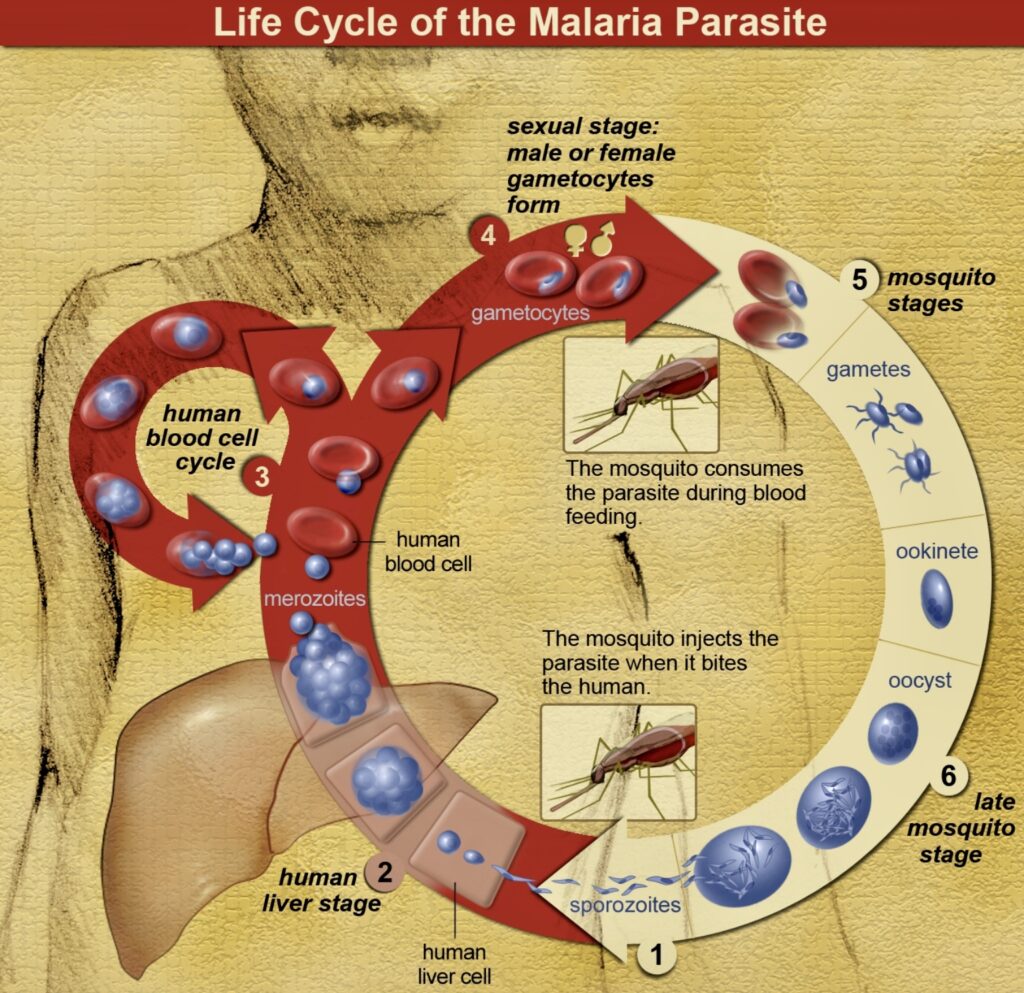

Life cycle of malaria parasite

Malaria-carrying mosquito

“The pandemic struck at a point when global progress against malaria had already plateaued,” the WHO deplored. “By around 2017, there were signs that the phenomenal gains made since 2000 – including a 27% reduction in global malaria case incidence and a nearly 51% reduction in the malaria mortality rate – were stalling.”

What most health experts think will happen come true. A just-released WHO data reveal that the pandemic indeed has disrupted malaria services, leading to a marked increase in cases and deaths.

According to WHO’s latest World malaria report, there were an estimated 241 million malaria cases and 627,000 malaria deaths worldwide in 2020. This represents about 14 million more cases in 2020 compared to 2019 and 69,000 more deaths.

Approximately two-thirds of these additional deaths – 47,000 – were linked to disruptions in the provision of malaria prevention, diagnosis, and treatment during the pandemic. These deaths could have been avoided if there was no pandemic.

“The COVID-19 pandemic may have impacted the delivery of services under our malaria elimination program, but this will not deter us from our vision of a malaria-free country,” said Health Secretary Francisco Duque III in a statement.

Most important tropical disease

The Geneva-based United Nations health agency calls malaria “the world’s most important tropical parasitic disease” as it “kills more people than any other communicable disease except tuberculosis.”

Like dengue fever, malaria is caused by a bite of a mosquito, which has about 2,000 species. The species that transmit malaria are classified in the genus Anopheles. There are some 400 species of Anopheles mosquitoes, but only about 70 species are known to be responsible for transmitting malaria.

About 30 are of major importance, responsible for a significant amount of all malaria cases around the world. Almost all Anopheles mosquitoes feed between sunset and sunrise. After feeding, they usually rest on the walls or ceiling while they digest the blood.

If bites could kill

To beat your enemy, you need to know your enemy well, health experts say. “Anopheles mosquitoes lay their eggs in water, which hatch into larvae, eventually emerging as adult mosquitoes,” the WHO says.

Male mosquitoes don’t bite; only females do. “The female mosquitoes seek a blood meal to nurture their eggs,” the WHO says. “Each species of Anopheles mosquito has its own preferred aquatic habitat; for example, some prefer small, shallow collections of fresh water, such as puddles and hoof prints, which are abundant during the rainy season in tropical countries.”

As a disease, malaria is caused by five types of plasmodium, a single-cell parasite transmitted by the bite of the female Anopheles. Most deaths, however, are caused by P. falciparum, whereas P. vivax, P. ovale, and P. malariae generally cause a milder form of malaria. The species P. knowlesis rarely causes disease in humans.

In the Philippines, the majority (72%) of malaria cases are due to P. falciparum and 26% to P. vivax, while 1.3% are due to other unspecified species, and 0.7% are mixed infections. “There has not been a systematic decline in the percentage of cases due to P. falciparum,” the WHO said.

Aside from mosquito bites, health experts say malaria can also be transmitted accidentally by blood transfusion or through contaminated needles or syringes. During pregnancy, fetuses can become infected with parasites from the blood of the mother.

Circle of life

According to a WHO publication, Rural Health, the malaria parasite is not simply transferred from one person to another but must live part of its life in the mosquito. It is for this reason that malaria is such a threat to health in the tropics but not in cooler countries or at high altitudes (where the temperature is lower).

“The cycle of malarial infection begins when a female mosquito bites a person with malaria,” explains The Merck Manual of Medical Information. “The mosquito ingests blood that contains malarial parasites. Once inside the mosquito, the parasite multiplies and migrates to the mosquito’s salivary gland.

“When the mosquito bites another person, the parasites are injected along with the mosquito’s saliva. Inside the person, the parasites move to the liver and multiply again. They typically mature over an average of one to three weeks, then leave the liver and invade the person’s red blood cells.”

It is at this point that the bitten person begins to feel the symptoms. “In a non-immune individual, symptoms usually appear 10–15 days after the infective mosquito bite,” the WHO says. “The first symptoms – fever, headache, and chills – may be mild and difficult to recognize as malaria. If not treated within 24 hours, P. falciparum malaria can progress to severe illness, often leading to death.”

Signs and symptoms

Children with severe malaria frequently develop one or more of the following symptoms: severe anemia, respiratory distress in relation to metabolic acidosis, or cerebral malaria. In adults, multi-organ failure is also frequent. In malaria-endemic areas, people may develop partial immunity, allowing asymptomatic infections to occur.

According to health experts, the symptoms are caused by the destruction of the red cells, causing anemia, the release of toxins into the bloodstream as the parasite bursts out of the red cells, and the blocking of small blood vessels throughout the body.

The patient becomes weaker. Danger signs include persistent vomiting, becoming confused, increasing difficulty in breathing, or having an epileptic fit. The patient may become unconscious through a condition known as “cerebral malaria.”

Any of these symptoms is a sign of a serious problem, and the patient needs urgent admission to a hospital or health center with the facilities for good inpatient care.

Treatment

Malaria is curable, and treatment is free, the health department says. On its website, the DOH says preventive and treatment services are being delivered by 3,166 public health facilities throughout the country.

The WHO says vector control is the main way to prevent and reduce malaria transmission. If coverage of vector control interventions within a specific area is high enough, then a measure of protection will be conferred across the community.

The WHO recommends protection for all people at risk of malaria with effective malaria vector control. Two forms of vector control – insecticide-treated mosquito nets and indoor residual spraying – are effective in a wide range of circumstances.

Sleeping under an insecticide-treated net (ITN) can reduce contact between mosquitoes and humans by providing both a physical barrier and an insecticidal effect. Population-wide protection can result from the killing of mosquitoes on a large scale where there is high access and usage of such nets within a community.

Antimalarial medicines can also be used to prevent malaria. For travelers, malaria can be prevented through chemoprophylaxis, which suppresses the blood stage of malaria infections, thereby preventing malaria disease.

For pregnant women living in moderate-to-high transmission areas, the WHO recommends at least three doses of intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine at each scheduled antenatal visit after the first trimester.

“Although there are only a limited number of drugs, if these are used properly and targeted to those at greatest risk, malaria disease and deaths can be reduced, as has been shown in many countries,” the WHO says.