By Henrylito D. Tacio

Featured image courtesy of SCP

Can a 12-year-old girl help fund a pioneering effort of restoring degraded coral reefs in the country’s second-smallest province?

Yes, if your name happens to be Sofia R. Pardo and you live in Camiguin, an island province that follows Batanes in terms of population and land area. She is involved in the reef regeneration, which the Sangkalikasan Producers Cooperative (SPC) is initiating.

SPC is a non-government organization at the forefront of reviving corals damaged by pollution and other destructive human activities.

Pardo’s interest in coral reefs started when she was 10 years and a graduating student of the International Baccalaureate Primary Years Program. “What I needed to do to finish off grade school was a project that was something I was passionate about,” she recalled.

After finishing the project, the students would have to present their results at the PYP Exhibition and based the project on one of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) of the United Nations.

“I always loved the sea and the beach,” she admitted, and so she chose the 17th goal, which is “life under water.”

Padro then collaborated with the SPC through Jose Rodriguez and became the youngest member of the organization. Thanks to the generous donations from various organizations like the Discovery Leisure company and several kind-hearted individuals, the funding raised by Pardo has contributed to the funding requirements needed by the SPC.

Two years ago, SPC directors couple Bunne Gamboa-Santos and Michael Santos traveled to the United States to learn the quick-growth fragmenting approach pioneered by Dr. David E. Vaughan, of the Mote Marine Laboratory in Florida.

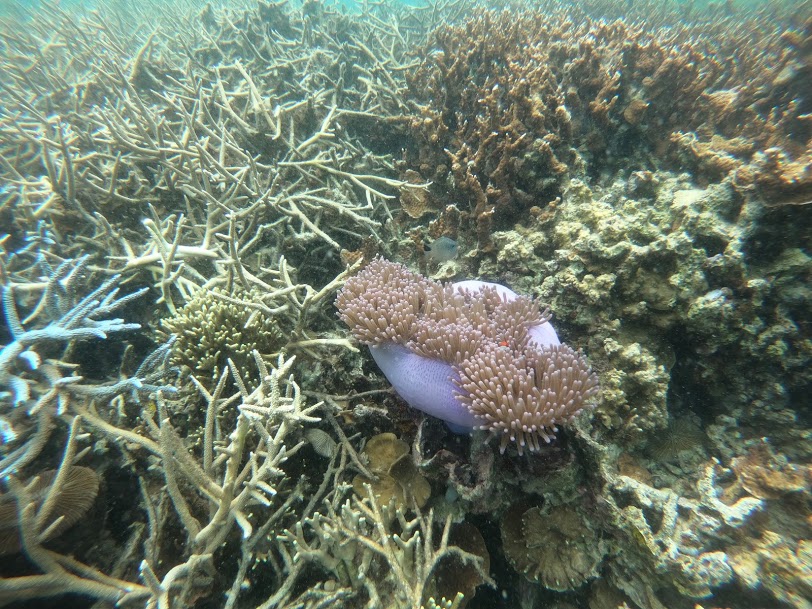

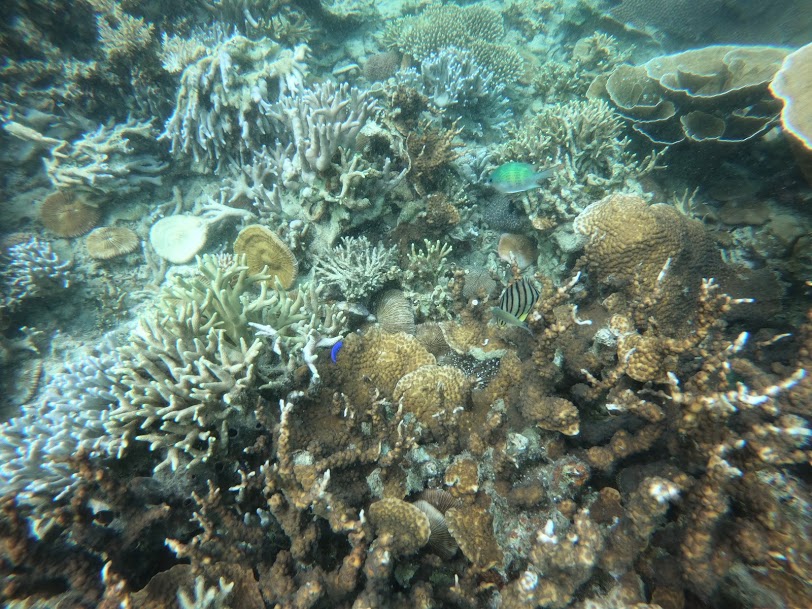

When they returned, they introduced the technology in Camiguin. It involves the process of micro-fragmentation and colony fusion of coral fragments. This differs significantly from the more common coral restoration methods that usually focus on branching species.

“In this technique, the massive corals – which normally have a slow growth rate – are fragmented or broken up using special equipment,” explained Alexandra Hill, a British marine biologist who headed the project, “and the corals exhibit a faster growth rate when fragmented.”

“Furthermore,” she added, “fragments from the same donor colony have the ability to fuse together when physically joined which increases their overall surface area and their chances of survival.”

With budget constraints, SPC innovated the protocols to fit local conditions.

Camiguin, located in the Bohol Sea and about 10 kilometers off the northern coast of Mindanao, was chosen as the project’s site since its reefs were degraded due partly due to a strong typhoon, which hit the island in 2014.

As a matter of fact, two government agencies, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) and the Department of Science and Technology (DOST), looked at conducting coral propagation and reef rehabilitation programs on the site, and the area became the home base and a model site for several coastal management programs.

“The site where we ran the (coral fragmentation) experiment has a relatively good condition due to previous restoration,” Hill noted. “Due to the small scale of the experiment, the team mostly consisted of members of the local SPC and volunteers from Camiguin Polytechnic State College.”

The initial findings of the study showed that it’s working. “Although our study is still far from complete, we were able to (totally) restore a portion of coral reefs within the bay area,” Hill reported.

The Philippines is home to over 400 local corals species, which is more than what is found in Australia’s famous Great Barrier Reef. Unfortunately, most of these species are now gone, and others are facing extinction.

The decline is thought to be due primarily to destructive human activities. “Many areas are in really bad shape due largely to unwise coastal land use, deforestation and the increasing number of fishermen resorting to destructive fishing methods,” said Dr. Porfirio M. Alino, a marine scientist and academician of the National Academy of Science and Technology.

Destructive fishing methods – ranging from dynamite blasts to cyanide poisons – are destroying vast reef areas—Fishermen blast reefs with dynamite to stun the fish. When fish float to the surface, fishers scoop up large quantities at once.

Another equally destructive fishing method is the “muro-ami,” a drive-in net used to fish in coral reefs.

Coral mining has also depleted the country’s reefs. Also contributing to the destruction of coral reefs in the Philippines are sedimentation from soil erosion due to deforestation in the uplands.

Other causes of the deterioration of coral reefs in the country: the quarrying of coral reefs for construction purposes; pollution from industry, mining, municipalities; and coastal population growth.

Aside from human activities, natural causes of destruction among coral reefs also occur. These include shallow tide, high temperature of surface water, predation, and currents and waves’ mechanical action.

Shallow tides usually expose corals to sunlight and to freshwater runoff, both of which are said to be lethal over several hours of exposure.

The high temperature of surface water is exacerbated by abnormal low tides, which leave shallow reefs exposed to sunlight, rainfall, and freshwater flows.

Then, there’s coral bleaching. This occurs when corals turn chalky white and begin to die. Coral bleaching happens when corals are under stress because of extreme sea temperatures or pollution. Corals evict their algal tenants and turn white as a result, explains Worldwatch Institute’s John C. Ryan.

The Philippine government is doing its best to save the country’s remaining coral reefs bypassing several laws. PD 1198, for instance, amends PD 1219 and limits permits to gather in limited quantities of corals for scientific or educational purposes only. FAO 163, Series of 1986, prohibits the use of “muro ami” and “kayaks” in all Philippine waters.