By Henrylito D. Tacio

Photos courtesy of PEF and AboitizPower

Her name literally means “daydream” in English, but it’s now a reality that Pangarap has finally reached her debut – if she were a human being. Last February 23, the eagle bred in captivity turned 22.

Thanks to the Aboitiz Power Corporation, the holding company for the Aboitiz Group’s investments in power generation, distribution, and retail electricity services, which adopted the eagle since 2010.

“That was the year when we were looking for a conservation effort done by the Philippine Eagle Foundation (PEF) to support,” Wilfredo Rodolfo III, then the corporation’s manager of the branding and communication division, told this author.

The Aboitiz Group of Companies decided to adopt an eagle as a symbol of their support. “We then held a contest within the company for the best name of our eagle,” he recalled. “The name Pangarap won.”

On why the endangered Philippine eagle, Rodolfo explained: “She symbolizes the hopes and dreams of the company and its members not only in wildlife conservation but also our dreams for our country to take flight like the majestic eagle.”

AboitizPower is the holding company for the Aboitiz Group’s investments in power generation, distribution, and retail electricity services. It advances business and communities by providing reliable and ample power supply at a reasonable and competitive price and with the least adverse effects on the environment and host communities.

The company is one of the largest power producers in the Philippines, with a balanced portfolio of assets located across the country. It is a major producer of Cleanergy, its brand for clean and renewable energy with several hydroelectric, geothermal, and solar power generation facilities. It also has thermal power plants in its generation portfolio to support the baseload and peak energy demands of the country.

The power company was one of the first to respond to the call of PEF for help, financially or otherwise.

“Our partnership with Aboitiz Power Corporation does not only sustain Pangarap but also our initiative to breed the species in captivity. Pangarap symbolizes our dream to one day produce enough suitably reared Philippine eagles to repopulate the wild. This dream can only be realized with the generosity and support of our partners like AboitizPower.”

Every year, the power company provide financial support for the eagle’s upkeep, research and conservation actions to guarantee the survival of the endangered bird. We are grateful for the company’s growing support to save our national bird.”

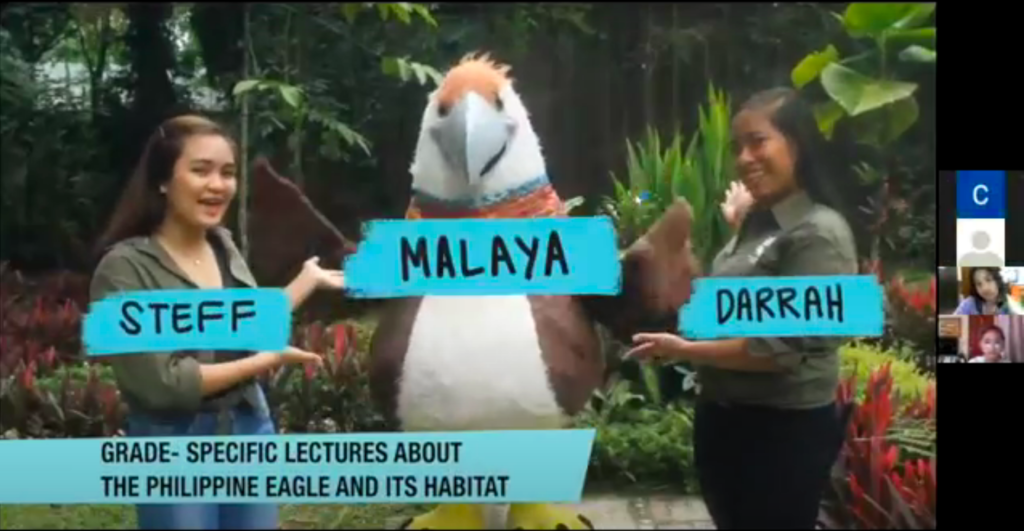

During the 22nd hatch day celebration, AboitizPower teamed up with the PEF to spread positive energy by hosting a fun and lively celebration via Zoom along with a week-long blast on Facebook, highlighting Pangarap and what she means to the country’s wildlife.

Grade school students and teachers from the Ateneo de Davao University were able to watch and learn more about the exotic bird of prey through games and activities with Malaya, PEF’s beloved mascot.

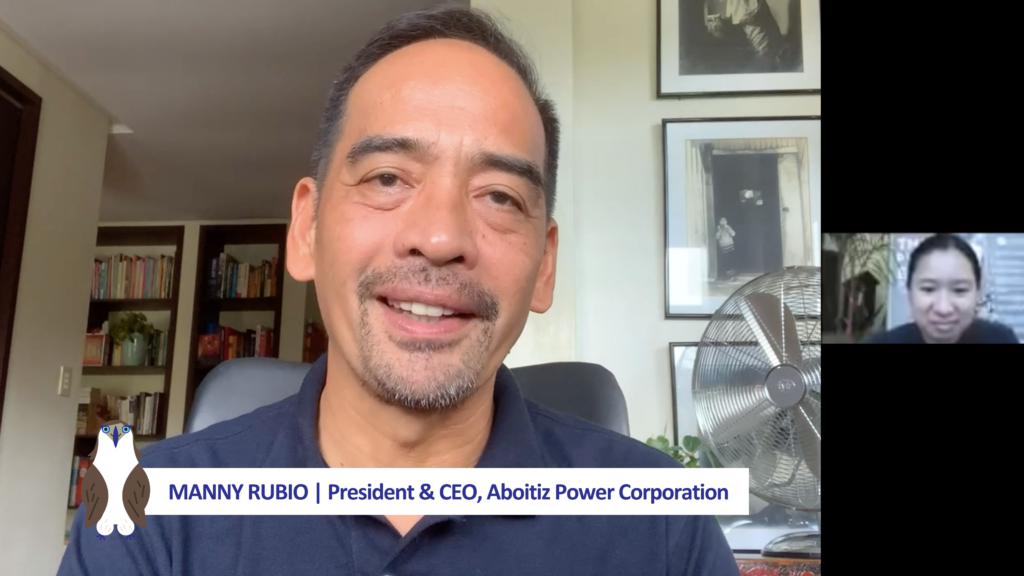

“To us, Pangarap is a national treasure and a symbol of hope for our country’s unique wildlife, and I want to give a big thank you to the Philippine Eagle Foundation for taking such good care of her over the years, even with all the challenges brought about by the pandemic,” said Emmanuel V. Rubio, AboitizPower president, and chief executive officer in a special hatch day message for Pangarap.

“We at AboitizPower are happy to be a partner in her upbringing. As we aim to spread positive energy all over the country and in all aspects of life, we look to drive towards our goal of sustainability and foster a healthy environment for generations to come,” Rubio added.

Pangarap is a product of the center’s captive-breeding conservation program through natural pairing. She is the offspring of the pair Biomate and Robinhood. While growing up, she was reared by a combination of hand and puppet rearing.

A few years back, she was transferred to her own enclosure, so she won’t be able to see other people in the adjacent lot. “Pangarap has now adjusted to her enclosure,” said a PEF statement. “The disturbance from the adjacent lot has now been addressed by covering the side of her enclosure.”

Studies have shown that a Philippine eagle can already produce an egg by the time she’s five years old. When Pangarap was already 13 years old, she was able to produce an egg but unfertilized since she didn’t have a male partner when it was conceived.

There are two ways of breeding an eagle at the center: natural pairing and artificial insemination. Pangarap is among the eagles at the center in Malagos, Calinan District in Davao City, to be artificially inseminated. “Once semen is collected, she will be stimulated for the production of fertile egg,” the press statement said.

In the past, many pioneering efforts to breed certain endangered species in captivity failed. According to Salvador, breeders of a captive eagle and other birds find it a Herculean task to induce captive birds to reproduce. Many factors like food, protection, and nesting needs have to be considered.

Salvador, who was named as one of The Outstanding Young Men in 2000 for “his contributions to the country’s wildlife conservation efforts,” cited five reasons why the eagle center resorted to the artificial insemination method.

These are: (1) while the male gets into all stages of the breeding cycle, he still fails to copulate; (2) most eagles at the center are already “sexually imprinted” on humans, meaning the eagle has already accepted a human as its sexual partner; (3) there is a shortage of unrelated sexually mature male eagles; (4) crippled or disabled eagles cannot have natural sex; and (5) some pairs of eagles of opposite sexes would rather kill one another than have sex.

Now fully matured, Pangarap is one of the few eagles who is still eligible to reproduce and regrow her species’ population.

The Philippine eagle is listed by the International Union of Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources as among the country’s threatened birds. In July 1995, then-President Fidel V. Ramos signed Proclamation No. 615, naming the Philippine eagle as the country’s national bird.

Ramos said that the bird is found only in the Philippines, and as such, it should be a source of national pride. If the national bird dies, the former president said, “so will all the country’s efforts at conserving its natural resources and treasures.”

It was English naturalist John Whitehead who discovered the bird in Samar in 1896. He called it a “monkey-eating eagle” based on the reports that the bird fed primarily on monkeys. So much so that the scientific name, Pithcophaga jefferyi, came out of that belief.

The word Pithocophaga was derived from two Greek words: “pitekos,” meaning “monkey,” and “phagien,” meaning “to eat.” The specific name jefferyi was Whitehead’s tribute to his father Jeffrey, who financed his expedition.

The bird was later renamed Philippine eagle under the administration of Ferdinand E. Marcos when it was learned that monkeys comprise “an insignificant portion of its diet,” which consists mainly of flying lemurs, civet cats, bats, rodents, and snakes.

Efforts to save the Philippine eagle was started in 1965 by Jesus A. Alvarez, then director of the Autonomous Parks and Wildlife Office, and Dr. Dioscoro S. Rabor, another founding father of Philippine conservation efforts.

General Charles Lindberg, an aviator, spearheaded a drive to save the bird (which he called as “the air’s noblest flier”) from 1969 to 1972. His vigorous campaign eventually led to the establishment of the eagle conservation program, which Congress supported by enacting Republic Act No. 6147 to protect the bird.

Today, PEF is trying to save the endangered bird from extinction. A non-government organization, it is funded almost entirely by private voluntary contributions. It was not until in 1987 that it started to invest in the work.

“The eagle center is probably the biggest tool we have in educating the people,” Salvador said. “The facility enables us to bring the Philippine eagle and other wildlife closer to our people.”

But the captive breeding is the center’s top program as its main objective is to augment wild populations of the endangered bird while serving as a “genetic insurance” for the species.

Studies conducted by the center indicate that more than 90% of fledglings and juveniles do not reach breeding age or adulthood primarily because of human persecution (mainly shooting followed by trapping-capture incidents). A Philippine eagle is considered an adult when it reaches the age of six to seven years.

If the old breeding pairs in the wild are not being replaced, Salvador said, it is more likely that the whole Philippine eagle population could suddenly collapse. “Before we know it, we’d probably lose the Philippine eagle. We’ll have a national bird that doesn’t exist,” Salvador warned.

Deforestation has been blamed for the fast disappearance of the world’s second-largest eagle. “The Philippine eagle has become a critically endangered species because the loss of the forest had made it lose its natural habitat,” he pointed out.

In the 1920s, the forest still covered 18 million hectares of 60% of the country’s total land area of 30 million hectares. It went down to 50% (15 million hectares) in the 1950s. In 1963, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization published data that placed forest cover of the country at 40% (12 million hectares).

By the 1970s, the forest cover shrunk to 34% (10.2 million hectares). From 1977 to 1980, deforestation reached an all-time high – over 300,000 hectares a year, according to a booklet published by Environmental Science for Social Change.

Between 2000 and 2005, the country lost about 270,000 hectares of forest a year, according to a study made by the regional office of FAO in Bangkok. A pair of Philippine eagles needs at least 7,000 to 13,000 hectares of forest as a nesting territory.

“Without the forest, the species cannot survive over the long term,” Salvador said. “Without the forest, not only the Philippine eagle will go extinct, but so will the dreams and aspirations of millions of marginal income families who rely on the forest to survive.”