Text and Photos by Henrylito D. Tacio Additional Photo by DENR

A group of fisherfolk based in barangay Adecor in Kaputian District of Island Garden City of Samal (IGACOS) are trying to save some of the country’s remaining endangered species of giant clams, locally known as taklobo.

The Adecor United Fisherfolk Organization, with more than a dozen members, are the caretakers of the giant clams that was transplanted by the Giant Clam Stock Enhancement Program of the University of the Philippines-Marine Science Institute (UP-MSI).

The Marine Reserve Park and Multipurpose Hatchery, as it is called, is under the supervision of the local government unit of IGACOS and is a project of the Davao del Norte State College.

Aside from preventing the disappearance of giant clams in the country’s waters, the organization also helps in raising awareness of the importance of giant clams and providing livelihood to members.

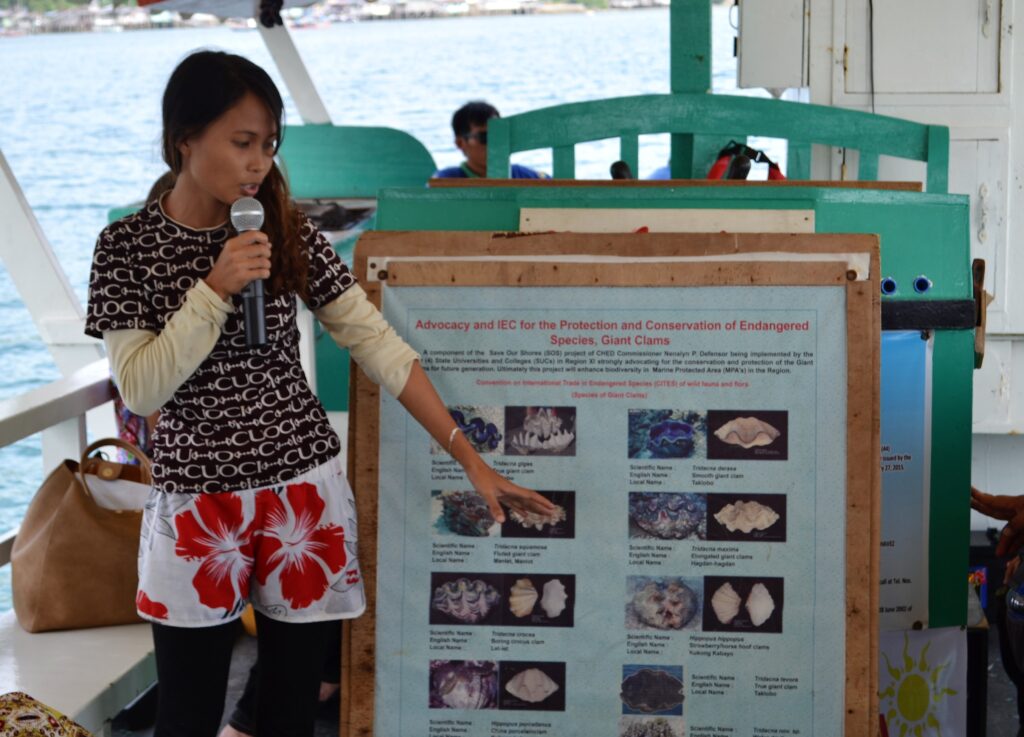

They do this through the Taklobo Tours which includes an hour of snorkeling. Visitors are brought by means of a motorized banca from the seashore to the floating cottage, where they are educated about the giant clams.

After giving some instructions, the visitors are told to wear a life jacket and given a snorkel and a mask. Then, they swim to the area where the giant clams are being raised. As the water is clear, they can see the endangered species up close.

Taklobo Tours started in 2013 and today is one of Samal’s tourist activities.

“Awesome and inspiring marine sanctuary that protects several species of giant clams,” one tourist commented. “With our snorkel masks on, we were led underwater by a certified guide to witness firsthand these amazing sea creatures. We also learned about their habitat, life cycle and feeding. A definite must-see.”

Actually, the 14-hectare giant clam sanctuary is a community-based Ecotourism Project whose aim is to promote biodiversity preservation, education, tourism, and livelihood.

“We raise awareness by informing the people who come how endangered these giant clams are and that there are now laws regarding its preservation,” said Joel Gonzaga, one of the members of the organization. “It is now prohibited to harvest them and there are some consequences if they do so – with fines up to three million.”

According to Gonzaga, there are four species of giant clams introduced in Samal waters; these are Tridacna gigas (true giant clam), T. deresa (smooth giant clam), T. squamosa (fluted giant clam), and T. hippopus (strawberry clam or bear claw clam).

All in all, about 3,500 giant clams were brought by the UP-MSI for possible stock enhancement in the area. Marine scientists have considered farming giant clams as a means of promoting biological sustainability and maintaining biodiversity of the species.

Unfortunately, only 2,196 remain of the original numbers of giant clams brought into Samal in 2001. But the good news is that the group was able to raise 800 juveniles thriving in the clean waters.

The giant clams are raised along with the coral reefs. In fact, they are key to the country’s endangered coral reefs, according to Dr. Cecilia Conaco, of the Marine Science Institute (MSI) of the University of the Philippines Diliman.

Dr. Conaco, who is MSI’s deputy director of the Bolinao Marine Laboratory, said giant clams build and shape reefs aside from filtering water and recycling nutrients. They also serve as food factories.

More importantly, they provide shelter for different organisms. Serving as substrates of corals and sponges, marine biologists say giant clams – which can live in the wild reportedly up to over 100 years – help increase the residence of fishes and act as hiding places for other marine organisms.

“Like most corals, some anemones, and other reef organisms, giant clams utilize a combination of methods to obtain food,” explains Oceana, an international organization focused solely on protecting the world’s oceans. “The majority of their energy is derived from symbiotic algae living within their cells, providing the clams with excess energy that they make via photosynthesis.”

In return, “the algae have a safe to live and receive the nutrients necessary to photosynthesize. The giant clams provide those nutrients by filtering feeding small prey from the water above the reef surface, which it siphons through its body. The beautiful, bright colors characteristic of individual giant clams are actually a result of the symbiotic algae.”

As giant clams cannot literally move due to their heavy weight (as much as 250 kilograms), they reproduce via external fertilization, where eggs and sperm are released into the water column at the same time. Although they are hermaphrodites, they cannot self-fertilize. “They are able to reproduce with other individuals that are close by,” Oceana explains.

Most Filipinos don’t know this and in fact, they have no idea about the real status of giant clams thriving in the country’s waters. Recently, these marine creatures made headlines when Chinese fishermen were caught poaching giant clams from the West Philippine Sea.

“(The extraction of giant clams) is an affront to our territory and our sovereignty,” then Presidential Spokesperson Salvador Panelo was quoted as saying by Manila-based reporters. “As far as we are concerned, that is our so we will be objecting to those intrusions.”

Giant claims may not be endemic to the country, but the Philippines is one of the few countries where they can be found. These bivalve mollusks reportedly live in the shallow coral reefs of the South China Sea, West Philippine Sea, Sulu Sea, Red Sea, but mainly in the Indian and South Pacific Oceans.

If the Philippines doesn’t watch out, giant clams may soon disappear from its waters. Dr. Conaco said the challenges to giant clam conservation in the country are overharvesting, habitat degradation, inefficient enforcement of national regulations, and unsustained support for conservation programs.

“We need to do something now before giant clams become extinct,” urges Dr. Rafael D. Guerrero III, former executive director of the Philippine Council for Aquatic and Marine Research and Development and now an academician with the National Academy of Science and Technology.

Giant clams may have existed even during the time when dinosaurs roamed around this planet. “They have been around for over 38 million years,” wrote Vicky Viray-Mendoza, the executive editor of Maritime Review Magazine. “Antonio Pigafetta, the Italian navigator who joined Ferdinand Magellan in his sea travels around the world, documented these giant clam species as early as 1521 in his journal.”

Of the 12 species of giant clams known to man, eight of them can be found in the coral reefs of the Philippines. Aside from the four species mentioned above, the other species were Tridacna crocea (boring clam), T. maxima (elongated giant clam), T. hippopus porcellanus (China clam), and T. noae ningaloo (Noah’s giant clam or teardrop clam).

The Switzerland-based International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has listed all eight giant clams as endangered species. In its IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, two species – T. gigas and T. deresa – as “vulnerable.” Considered rare to find is T. hippopus porcellanus. The rest are just as endangered but are misclassified as “lower risk/conservation dependent.”

According to Viray-Mendoza, who retired as World Bank group operations analyst and has special interest in marine environment, these various species of giant clams live in Palawan, Eastern Samar, Maricaban Island, Silaqui Island (in Bolinao, Pangasinan), Batangas (particularly Anilao), Samal Island (in Davao), Negros, and Tawi-Tawi.

With the help of some non-government organizations, giant clams have been restocked at the following sites: Anda, Pangasinan; Masinloc, Zambales; Calape, Bohol; Camotes Island, Cebu; Ilocos Norte; and Hundred Islands National Park.

Giant clams are described as “solar marine species,” which means they need the sun to grow, survive and thrive. According to Viray-Mendoza, giant clams live in flat coral sand or broken corals, and can be found in shallow warm waters and depths up to 20 meters.

“The giant clam gets only one chance to find a nice home,” according to a report released by the National Geographic. “Once it fastens itself to a spot on a reef, there it sits for the rest of its life.”

In her in-depth report, Viray-Mendoza noticed that most of the giant clams that used to be abundant in the Philippine waters have dwindled. “Its populations are diminishing quickly, and the giant clams have become extinct in areas where they were once abundant,” she deplored.

Giant clams are also listed in the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES), an international agreement between governments whose aim is to ensure that international trade in specimens of wild animals and plants does not threaten their survival.

Giant clams are harvested for food. “Though the soft body parts account for about 10% of the body weight, it is nearly pure, healthy protein,” Oceana says.

The meat of giant clams reportedly fetches P6,000 to P8,000 ($120 to $160) per kilogram. In Japan, where it is known as “himejako,” the meat is considered a delicacy. Some Asian foods include the meat from the muscles of clams. In China, large amounts of money are offered for the adductor muscle, which the Chinese think to be an aphrodisiac.

There’s some truth to the claim of being an aphrodisiac. “American and Italian researchers teamed up to analyze the bivalves, and found that clams rich in amino acids that trigger an increase in sex hormone levels,” Viray-Mendoza wrote. “Also, the giant clam’s high zinc content can aid in the production of testosterone.”

These days, giant clams are valued for their shells. Touted as “jade of the sea,” the shells are seen as an alternative to ivory from elephant tusks. A Science feature reported these shells are sold from P150,000 ($3,000) to P600,000 ($12,000). In China, where it is a hit, they are made into carvings, jewelry and other ornaments – “as status symbols for the wealthy and as protective charms in Chinese Buddhism.”

To save the giant clams, the government included the species in the Philippine Fisheries Code (Republic Act 8550). The Code prohibits the act of collecting, selling and exporting giant clams. Should anyone caught violating the law, the person will be fined administratively, “three times the value of the species,or P300,000 to P3 million.”

In addition, the person committing the unlawful act will be imprisoned from five to eight years and a fine equivalent to twice the administrative fine, and forfeiture of species.

“Giant clams are being protected through the Marine Protected Areas (MPAs),” said Dr. Guerrero. MPAs restrict human activity for a conservation purpose, typically to protect natural resources.

Dr. Guerrero believes there’s still hope for giant clams. “To save our giant clams, we should protect them in the wild from poachers (particularly foreigners) and promote their sea farming,” he suggested. – ###