Text and Photos by Henrylito D. Tacio

While some schools in provinces have already started face-to-face (F2F) classes, they will still resume in November in Davao City. By the time five-day F2F classes start again, the anti-bullying ordinance will hopefully also be out, according to Councilor Lorenzo Benjamin “Enzo” Villafuerte.

Villafuerte, chair of the Committee on Civil, Political and Human Rights for the 20th City Council, proposed the anti-bullying ordinance last July. It has already passed on the first reading.

“With the collaboration of the Philippine National Police and other agencies, we can make this ordinance the best it can be and address the specific needs of Davao City as a whole,” the councilor said in a privileged speech quoted by Edge Davao’s Maya Padillo.

Even though it is common, bullying has received little attention, possibly due to the belief that fighting among children is part of school culture. “Away bata” is the common excuse for it – it’s “normal” or “a rite of passage” for children.

But that should not be the case. Bullying is bullying, and school should be a place where children should learn about life and living and not violence. “A school is a student’s second home, and assumed to be one of the safest places for children. Unfortunately, for some this is where they experience abuse,” says a statement from the United Nations Children Fund (UNICEF).

Schools these days have become settings that expose children to violence not just from their classmates and peers but also from their teachers and even school personnel. So much so that in 2012, the Department of Education (DepEd) issued its Child Protection Policy.

Fourteen years ago, a baseline survey involving 2,442 children from 58 public schools in the country was conducted by the Plan Philippines, an organization whose mission is to promote and protect the rights of children.

“Results of the survey show that peers perpetrate most forms of violence experienced by children,” commented Plan Philippines country director Michael Diamond. “Ridicule and teasing by peers are the most common experiences. Across three age ranges surveyed, the incidence of ridicule and teasing was reported to have been experienced by 50 percent among children in Grades 1 to 3; 67 percent among children in Grades 4 to 6; and 65 percent among children in high school.”

But when does bullying happen? “Bullying occurs when the target has no opportunity or way to balance the equation,” Regina Sevilla-Sibal, an experienced school administrator and educator, told Philippines Graphic.

Sibal cited an example: “There’s a group of kids teasing one child because they think he’s too smart for his own good. But when they’re in class, these kids ask for the smart one’s notes. However, the smart child refused to deal with these kids. Is this bullying? No, because that child has a way to balance the equation.”

While bullying gets a lot of attention from parents and teachers in industrialized countries (like those being depicted in Hollywood movies), such is not the case in our country. Dr. Honey Carandang, a noted Filipino psychologist and author, has often expressed her disappointment over the seeming lack of concern that school authorities have shown towards bullying incidents that take place right under their noses.

“It’s really sad how, instead of being helped, the bullied child is sometimes even blamed for the bullying that has taken place,” Dr. Carandang deplored, adding that there should be more programs put in place to further educate teachers and administrators about the dangers of bullying and to teach them to be more sensitive.

“There are three persons who need to be helped and empowered here – the bully, the bullied, and the bystander,” Dr. Carandang. She further said that everyone needs to be part of the solution and that if a teacher or student is in a class or is a witness to a bullying incident elsewhere on campus and does nothing, then that person is as much a part of the problem as the bully.

You may be wondering, “what turns these children into bullies?” There is no data the Philippines can speak of. But in the United States, but researchers led by Kris Bosworth of the University of Arizona collected information from 558 students in grades 6 to 8, then divided the students into three groups: 228 students rarely or never bullied anyone; 243 reported a moderate level of bullying; and 87 reported excessive amounts of bullying.

“Those who reported the most bullying behavior had received more forceful, physical discipline from their parents, had viewed more TV violence and showed more misconduct at home,” wrote Dr. Richard B. Goldbloom in an article that appeared in Reader’s Digest.

“Thirty-two percent lived with a stepparent, and 36 percent lived in a single-parent household. Bullies generally had fewer adult role models, more exposure to gang activity and easier access to guns. This partly explains why bullies need help as much as victims: Many learn their behavior by example.”

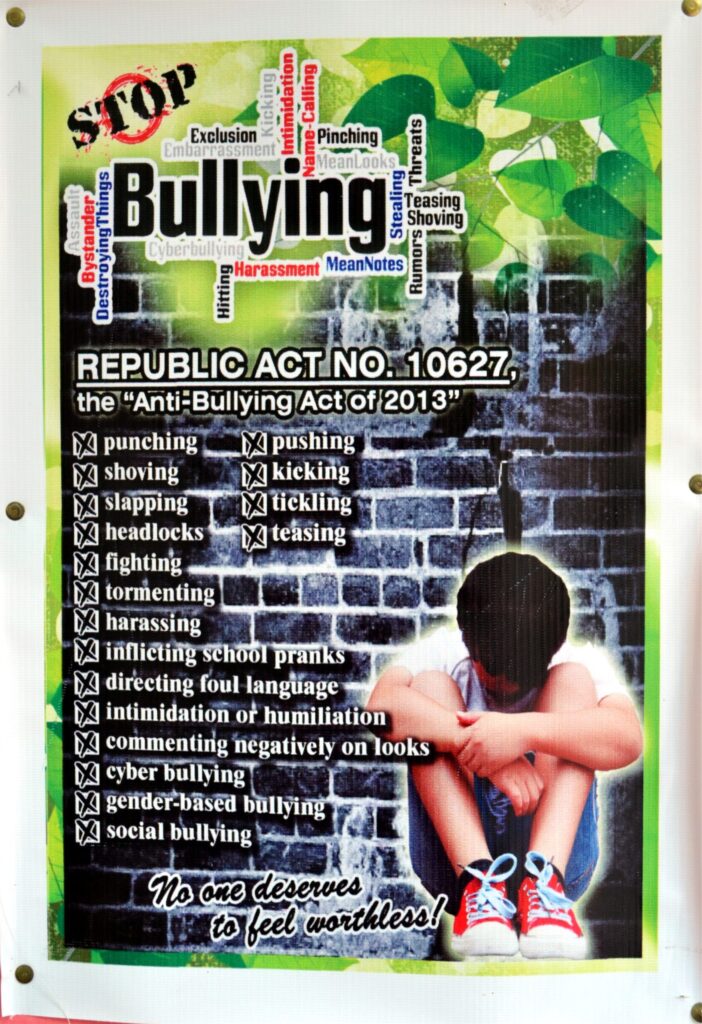

In 2013, then President Benigno S. Aquino III signed the anti-bullying bill into law, Republic Act 10627. Senator Juan Edgardo “Sonny” Angara, one of the principal authors of the bill, called it “a huge step in protecting our children from the earliest forms of violence.”

The Anti-Bullying Act of 2013 requires elementary and secondary schools to adopt policies to prevent and address bullying.

In the measure proposed by Villafuerte in Davao City, he wanted to include “colleges, vocational schools, graduate schools, workplaces, and other workplaces and cyberbullying.”

“The spirit of this ordinance,” Villafuerte stressed, “is to punish the sin not the sinner.”