Coral bleaching: Turning colorful undersea garden into white graveyard

By Henrylito D. Tacio

Not too many Filipinos have seen coral reefs underwater, those described as Eden beneath the seas. Much less they hear of coral bleaching, the phenomenon which turned the colorful sea garden into white graveyard.

Early this year, the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) predicted the world will experience the fourth and worst mass coral bleaching event in history. And Last April 15, during the International Coral Reef Initiative, NOAA finally sounded the alarm.

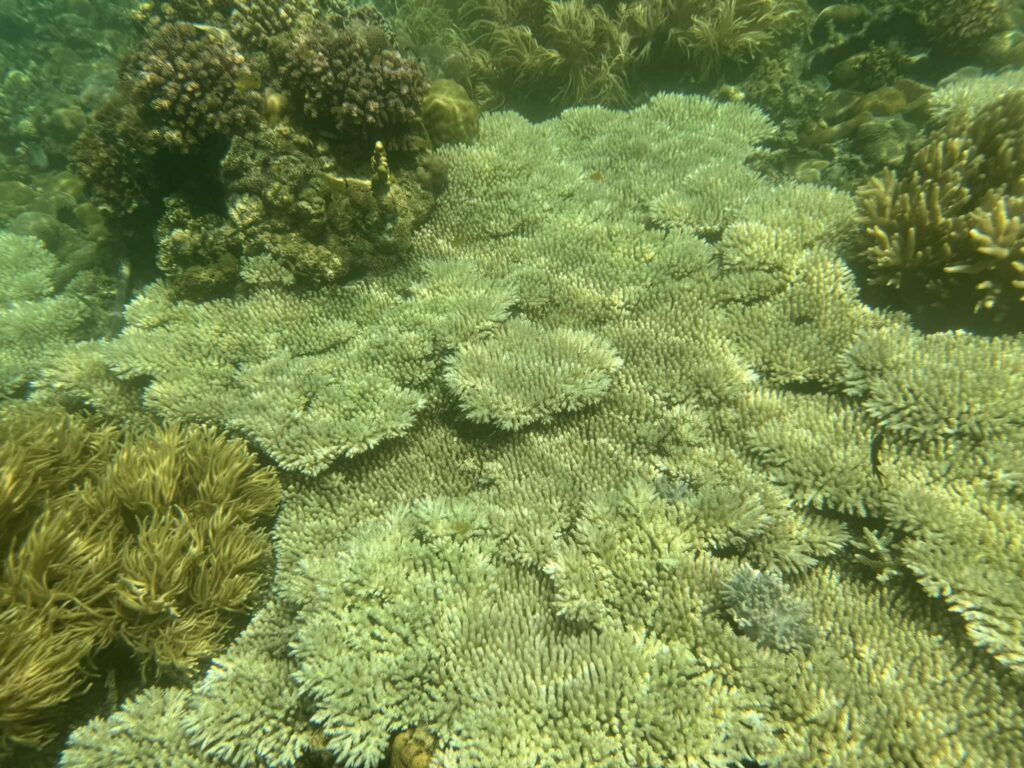

The Philippines is not spared from such a phenomenon. Iñigo Taojo posted on the website of Philippine Coral Bleaching Watch on October 21 that coral bleaching was on-going in the northern Davao Gulf. One of the pictures in this feature was from the said post. It is specifically happening on Kopiat Island of Mabini, Davao de Oro.

Coral bleaching in Kopiat Island of Mabini, Davao de Oro. (Photo courtesy of

Iñigo Taojo)

Esquire reported that bleaching was also observed in such places as Punta Baja, Palawan, Zambales, and Negros Occidental.

“Fortunately, other places were spared, such as the area around Dumaguete and Dauin in Negros Oriental,” Esquire reported. “Likely, colder currents coming from the east have spared the corals in this location from too much heat stress. Local factors can make a big difference when it comes to coral bleaching.”

In July, the Philippine Coral Bleaching Watch listed the northern part of the country, including Batangas, Marinduque, Negros, and Zamboanga as areas on alert level 2, meaning “significant bleaching is expected with coral mortality likely.”

Coral bleaching is most likely to happen in areas on alert level 1, particularly in central part of the country and Southern Mindanao.

The last time the Philippines experienced a mass coral bleaching event was in 2020. One of the worst hit was the Bolinao-Anda Reef Complex in Northern Luzon. The result of the study conducted in the area by the University of the Philippines Marine Science Institute (UP MSI) was “damning.”

As published in the Marine Biology Research, out of 2050 soft coral colonies documented, 51.36% exhibited indications of bleaching. Although the presence of bleaching does not necessarily signify the death of the coral, the depletion of the zooxanthellae algae, which provide the coral with its coloration, suggests that the coral was progressing towards a critical state.

The Philippines consists of more than 7,100 islands, a significant number of which are bordered by fringing coral reefs. With a total reef area of approximately 25,000 square kilometers, it ranks as the third largest globally, and its waters are renowned for possessing the highest biodiversity of corals.

Overfishing, destructive fishing, and decades of pollution have taken a toll on the country’s coral reefs. a negative impact. But in recent years, the biggest concern is climate change, a long-term change in the average weather patterns that have come to define Earth’s local, regional and global climates.

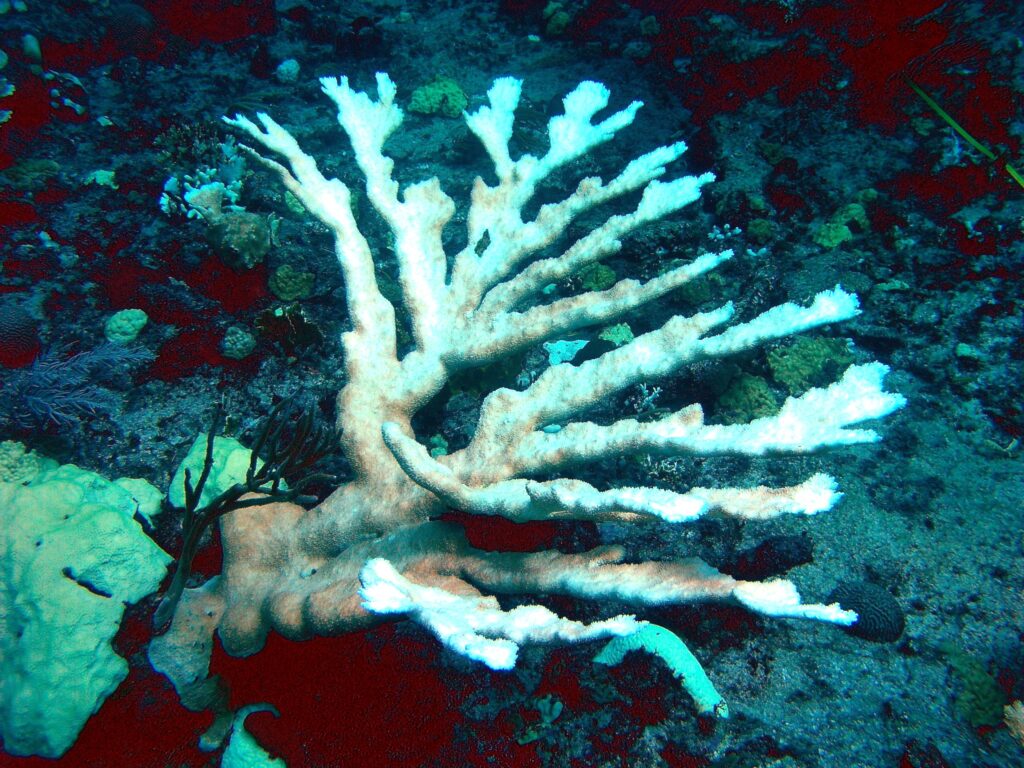

Coral undergoing bleaching (Photo courtesy of NOAA).

Coral reefs are among those that are greatly affected by climate change. A sudden or abrupt change in temperature is bad for corals. It leads to stress that causes coral bleaching, and eventually, death of corals. “Bleaching is not a good thing,” explained Dr. Terry Hughes, a distinguished professor at James Cook University told Edge Davao. “Thermal stress due to global warming is not good.”

According to Dr. Hughes, as global warming intensifies, coral bleaching would also increase at an unprecedented level. “Bleaching events are expected to increase in terms of frequency,” said Dr. Hughes, a fellow of the Australian Academy of Science.

“The surface of the world’s oceans has warmed by 0.7°Centigrade, resulting in unprecedented coral bleaching and mortality events,” said the statement, which was drafted by a working group of eminent scientists, released during the International Coral Reef Symposium (ICRS) in Cairns, Australia.

In a series of journals some years back, Science reported that climate change could trigger the death of coral reefs, with coral bleaching being the clearest sign.

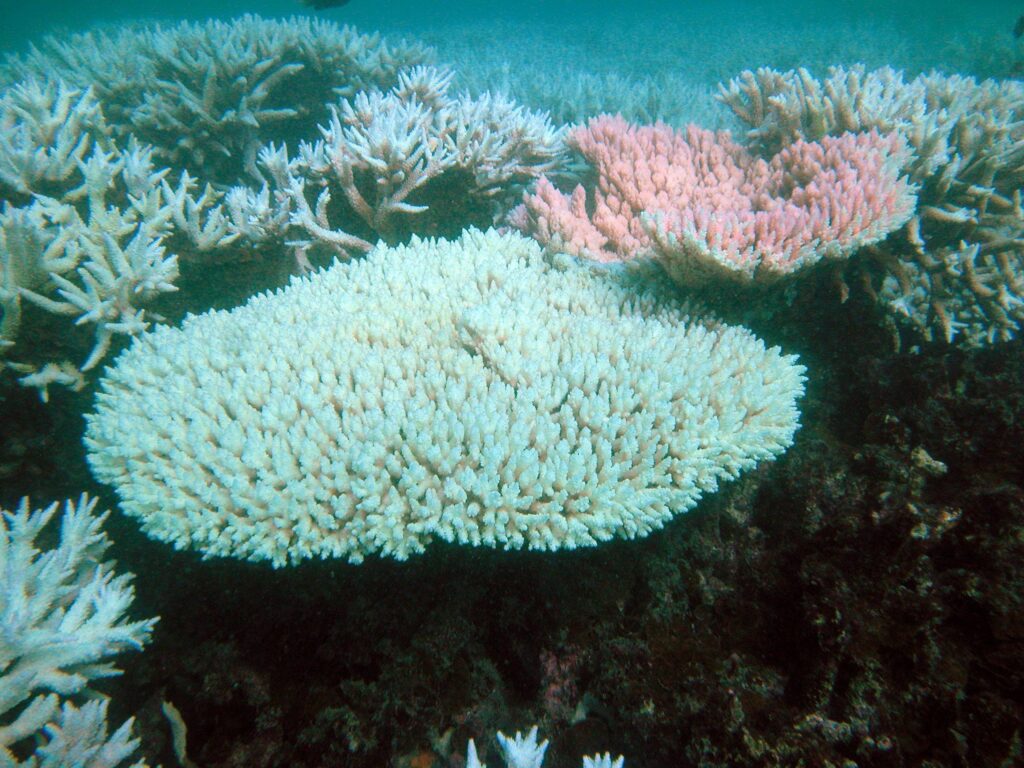

Corals grow in the warm waters, but many of them are near the limits of their tolerance for high temperatures. Bleaching is a breakdown of a “complex biological system” that corals have evolved in order to survive. Each coral formation is a colony of hundreds or thousands of tiny organisms (known as polyps) that jointly build a skeleton that forms the reef.

The outside layer of each coral polyp is inhabited by tiny one-celled plants which scientists called zooxanthellae. It is these organisms that give the coral its bright colors, and when expelled due to warmer water or some other stress, coral appears bleached (that is, go pale or snowy-white).

Without zooxanthellae, the coral cannot survive for long. “When subjected to extreme stress (like high temperature of surface water),” explains Worldwatch Institute’s John C. Ryan, “corals jettison the colorful algae they live in symbiosis with, exposing the white skeleton of dead coral beneath a single layer of clear living tissue. If the stress persists, the coral dies.”

The Management of Bleached and Severely Damaged Coral Reefs traced coral bleaching as far back as 1870. However, since the 1980s, bleaching events have become more frequent, widespread and severe.

In the first months of 2002, a wave of bleaching swept coral reefs around the world with scientists linking the events to climate change. The majority of bleaching records came from the Great Barrier Reef in Australia with others from reefs in countries including the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Japan, and off the Florida coast of the United States.

In 2010, as much as 95% of the corals in the Philippines suffered bleaching after a warming event. “The bleaching has been observed at many other sites around the Philippines featuring mass mortality of corals,” a news report said.

Recovery of severely damaged reefs caused by bleaching can take a long time, even on relatively healthy reefs. In addition, “the corals that repopulate a damaged reef may be significantly different from what existed before bleaching,” the fact sheet further stated.

Recovery is even slower if there are other stressors like poor water quality, overfishing or disease. “Where reefs are already stressed, recovery can take many decades, or even centuries,” the fact sheet said. “(But) a healthy, resilient reef will recover more quickly from bleaching.”

In some instances, even if corals survived from bleaching, they are now more susceptible to diseases, according to a study which appeared in the journal Ecology. “Traditionally, scientists have attributed coral declines after mass bleaching events to the bleaching alone,” says Marilyn Brandt, the leader of the study.

Warmer water temperatures can also lead to increased incidences of coral disease, which, unlike most bleaching, can cause irreparable loss of coral tissues. In many cases, bleaching and disease occur concurrently on coral reefs.

Brandt and her colleagues wondered if the occurrences of bleaching and disease were linked beyond simply occurring under the same conditions. “Coral bleaching and coral diseases are both related to prolonged thermal stress,” says Brandt.

Closer look of coral bleaching. (Photo courtesy of NOAA).

The warming brought by climate change is merely one of the numerous challenges confronting the coral ecosystems in the Philippines. The UP MSI has consistently disseminated updates regarding the detrimental effects of the Mindoro oil spill, which has adversely impacted not only our marine environment but also the industries and communities reliant on it for their livelihoods.

Christine Baran, who headed the coral bleaching study in the Bolinao-Anda Reef Complex, emphasized the growing human population and the significant anthropogenic disturbances that accompany it.

Baran noted that oil spills represent just one of the many ways in which human activities can inflict damage on marine ecosystems, with illegal fishing posing an additional threat.

Addressing this issue requires more than scientific intervention alone. Rhea Mae Luciano, a study co-author, said that safeguarding the reefs from further degradation necessitates collaborative efforts across various sectors of society.

“It requires cooperation from different institutions, agencies, and the communities,” Luciano pointed out. “The solutions and answers do not happen in a snap of a finger.”

Her words echoed the same concern of the Consensus Statement that was released during the ICRS in Australia. “Coral reefs are important ecosystems of ecological, economic and cultural value yet they are in decline worldwide due to human activities,” it said. “Land-based sources of pollution, sedimentation, overfishing and climate change are the major threats, and all of them are expected to increase in severity.”

All over the world, coral reefs are facing death not only from bleaching but from other causes. Before it is too late for the world to wake up one day without coral reefs, Dr. Simon Donner urged that something must be done now. He compared the global community to that of riding on a big ship like Titanic heading for oblivion.

“We have to hit the brakes to slow down from moving to hit the iceberg,” urged Dr. Donner, a Canadian scientist based at the University of British Columbia. “We have to find something to lessen the impact of coral bleaching and other stressors from destroying the coral reefs.