Text by Henrylito D. Tacio

Photo credits: Gregory C. Ira

When it comes to Philippine agriculture, farmers usually come first. So much so that fishers are neglected in terms of support and development. In fact, the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic (BFAR) is the only attached agency of the Department of Agriculture.

While the total land area of the Philippines is 300,000 square kilometers, its bays and coastal waters cover an area of 266,000 square kilometers, and its oceanic waters is 1,934,000 square kilometers.

The country’s total length of coastline is 36,289 kilometers, much longer than that of Japan, Australia, and the United States. In fact, it is the fifth longest coastline in the world – after Canada, Norway, Indonesia, and Russia.

About 60% of the country’s municipalities and cities are coastal, with 10 of the largest cities located along the coast, including Metro Manila, Metro Cebu, Iloilo, Davao, Cagayan de Oro, and Zamboanga.

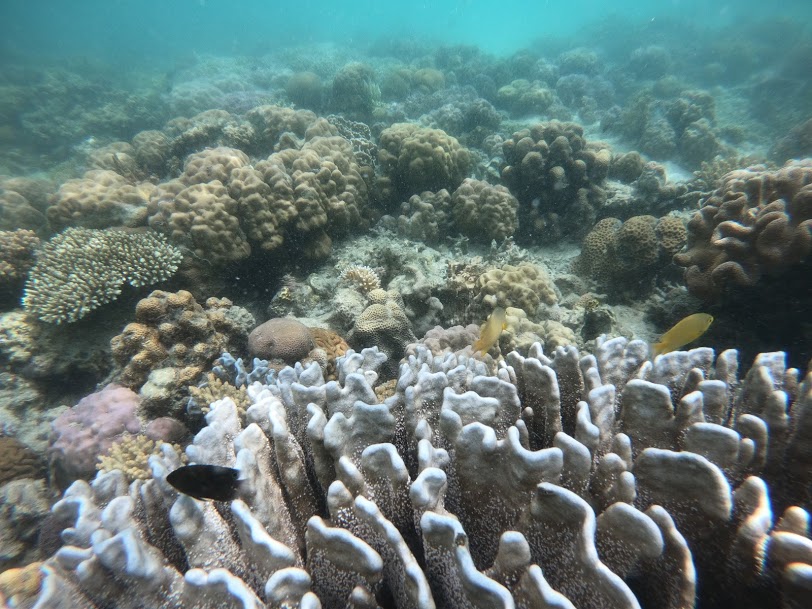

The Philippines is part of the Coral Triangle, the epicenter for marine biodiversity and what is considered the Amazon of the Sea. The Coral Triangle is “an area with more species of fish and corals than any other marine environment on earth,” says the Unico Conservation Foundation.

The Coral Triangle – so named because of its distinct triangular shape – spans 648 million hectares off the coasts of Indonesia, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, Solomon Islands, and Timor-Leste. Among these countries, the Philippines is considered the world’s “center of marine biodiversity,” according to the World Bank, “because of its vast species of marine and coastal resources.”

The coral reef area is considered the second largest in Southeast Asia – after Indonesia. Estimated at 26,000 square kilometers, it holds an extraordinary diversity of species. So far, scientists have identified 915 reef fish species and more than 400 scleractianian coral species, 12 of which are endemic, the BFAR reports.

Unfortunately, the beautiful coral reefs are on the verge of extinction. The Inventory of the Coral Resources of the Philippines in the 1970s found only about 5% of the reefs to be in excellent condition, with over 75% coral cover (both hard and soft).

Another study conducted in 1997 showed only 4% of reefs in excellent condition (75% hard or soft coral cover), 28% in good condition (50-75% coral cover), 42% in fair condition (25-50% coral cover), and 27% in poor condition (less than 25% coral cover).

But not all coral reefs in the country are on the verge of destruction. Early this year, the Davao regional office of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) conducted scuba diving in various areas in Davao Occidental to check on the conditions of the coral reef and other living organisms.

The first dive site was in barangay Bukid in San Jose Abad Santos. About 500 meters offshore, the reef was observed “to be in good physical condition due to the presence of a variety of fish species.”

“As fish and other marine species thrive in the said area, we are looking forward to declaring it as one of the marine protected areas in Region XI,” said Bagani Fidel A. Evasco, the DENR’s regional executive director.

In barangay Calian in Don Marcelino, the same observation was made: good physical condition. “Most of the fish that were observed are residents of the reef, which means that it is where they inhabit and reproduce,” the DENR said.

The environment department also conducted rapid coral reef assessment in barangay Tubalan in Malita. “The coral reef outside of Tubalan cove presents a variety of marine species like fish and sea turtles and is in excellent condition,” the report stated.

The excellent status of the area was also attributed to the Bantay Dagat patrollers “who are regularly monitoring and patrolling within its municipal waters” as part of the tasks of the local government unit’s preservation and protection mechanism.

Evasco described coral reefs as “highly fragile.” He went on further explaining that “the fish that live and grow on coral reefs are important food and livelihood sources for the people, especially in coastal areas.”

Unfortunately, those coral reefs in Davao Occidental seem to be an exception. In fact, leading marine scientists ranked the coral reefs in the Philippines as among the most threatened in Southeast Asia.

“Nowhere else in the world are coral reefs abused as much as the reefs in the Philippines,” deplored Don E. McAllister, who once studied the cost of coral reef destruction in the country.

In its website, the BFAR singled out destructive fishing techniques as among the largest contributors to reef degradation.

“Muro-ami, a technique that involved sending a line of divers to depths of 10-30 meters with metal weights to knock on corals in order to drive fish out and into waiting nets was extremely damaging to reefs, leading to its ban in 1986,” the BFAR reported.

But that’s just one. “Rampant blast fishing and sedimentation from land-based sources have destroyed 70% of fisheries within 15 square kilometers of the shore in the Philippines, which were some of the most productive habitats in the world,” the BFAR noted.

Cyanide fishing, employed since 1962 to collect aquarium fish, is another destructive fishing method. “Using cyanide tablets obtained from drugstores, collectors squirt the cyanide-laced water solution from plastic bottles on coral formations where marine fishes abound,” explains Dr. Rafael D. Guerrero, a national scientist with the National Academy of Science and Technology.

Despite several attempts to stop these destructive fishing methods – through increased enforcement, larger penalties, and educational campaigns – they persevere. “Many fishers have brought destructive practices to new areas,” the BFAR said. “Many operations have shifted to more remote, pristine areas such as the Palawan group of islands, the Sulu archipelago, parts of the Visayas, and western Mindanao.”

Coastal development, farming, aquaculture, and land-cover change have also threatened the country’s coral reef ecosystem. “Over 80% of original tropical forests and mangroves have been cleared, increasing sediment outflow onto reefs,” the BFAR said. “Mangroves continue to be cut and the areas converted to fishponds, a change that allows more nutrients and sediment to reach reefs.”

Aside from human activities, natural causes of destruction among coral reefs also occur. These include extremely low tide, high temperature of surface water, predation, and the mechanical action of currents and waves.

Extremely low tides usually expose corals to sunlight and to freshwater runoff, both of which, according to marine scientists, are lethal for coral reefs if they are exposed for several hours.

High temperature of surface water is exacerbated by abnormally low tides which leave shallow reefs exposed to sunlight, rainfall, and freshwater flowing. These environmental disturbances, experts claim, cause reefs to lose 70% to 90% of their living coral cover to depths of 15-18 meters.

In recent years, corals are exhibiting a new kind of degradation: massive bleaching.

“The first ever mass-bleaching event occurred in 1998-99,” the BFAR reported. “It began at Batangas in June 1998 and then proceeded nearly clockwise around the country, correlating with anomalous sea-surface temperatures. Most reefs of northern Luzon, west Palawan, the Visayas, and parts of Mindanao were affected.”

In terms of productivity, good coral reef areas can produce as much as 30 tons of fishery products per square kilometer in a year, according to Dr. Angel C. Alcala, a marine scientist who’s a recipient of the Ramon Magsaysay in 1992 for his pioneering efforts in restoring and conserving the coral reefs in the country.

Fish is the second staple food of Filipinos next to rice. On average, every Filipino consumes about 98.6 grams of fish and fish products, according to the Food and Nutrition Research Institute of the Department of Science and Technology.

“Coral reef fisheries provide livelihood for more than a million small-scale fishers who contribute almost US$1 billion annually to the country’s economy,” reports Dr. Alan T. White, author of Philippine Coral Reefs: A Natural History Guide.

In addition, coastal tourism brings substantial economic benefits to the country as it is a source of foreign exchange. The Asian Development Bank reported that in the mid-2000s, tourism generated $16.3 billion, accounting for 9.1% of gross domestic product.

There are three major types of coral reefs, according to Dr. Alcala. These are fringing type (those found on the edges of islands and which constitutes 30% of the country’s coral reefs); the barrier type (best exemplified by the Dajanon Reef of Central Visayas); and the atoll (of which the Tubbataha and Cagayan Reef in the Sulu Sea are ideal examples).

Most of the corals in the country are found in the Palawan group of islands, which includes the Kalayaan Islands group, accounting for 41.5%, according to State of the Coral Triangle: Philippines, published by ADB. The corresponding percentage share for the Visayas region is 29.1%, that for Mindanao is 18.1%, and for Luzon and Mindoro, 11.3%.

The corals most Filipinos know are actually the dried and bleached skeletons of soft-bodied animals that live in the warm, sunlit waters of tropical seas and look more like plants and rocks than animals.

The main part of the real coral is the polyp – the extraordinary flower-like animal with a tube-like body and finger-like tentacles. “Coral polyps get nutrition in two ways,” explains Lindsay Bennett, author of globetrotter island guide, Philippines. “They catch their food by means of stinging tentacles that paralyze any suitable prey – microscopic creatures called zooplankton – and also engage in a symbiotic relationship with zooxanthellae that live within the polyp structure.”

Coral polyps reproduce in two ways: asexually (by the division of existing individual polyps) and asexually (by combining egg and sperm from two different polyps). “This results in a free-swimming polyp that will be carried by ocean currents to find a new colony and commence a new reef,” Bennet writes.

Coral reefs are among the natural resources of the Philippines, and they must be protected and conserved. The only way to save coral reefs from extinction and restore their productivity is to limit access to them.

“This is no mean task,” said the late Edgardo D. Gomez, a national scientist who was the founding director of the Marine Science Institute at the University of the Philippines Diliman. “But it seems it is the only means we can save our coral reefs from disappearing in this part of the world.”