Text by Henrylito D. Tacio

Photos by Gregory C. Ira

Darrell Blatchley was still sleepy but already awake as he had to dive into the waters near the Pearl Farm Beach Resort, where he stayed for the night. He was excited; after all, he had been raring to see what others had been telling him.

“If you ever get the chance to dive, do it here; you will see what the best of the Davao Gulf has to offer,” says Blatchley, an American who has been living in Davao City for almost half of his life. “Fishing is strictly prohibited, so the fish are plentiful and big. The fish are not afraid of you, so they come in close as if they want to say hi!”

Among those that he saw while diving was the parrotfish, triggerfish, barracuda, and the poisonous but impressive lionfish.

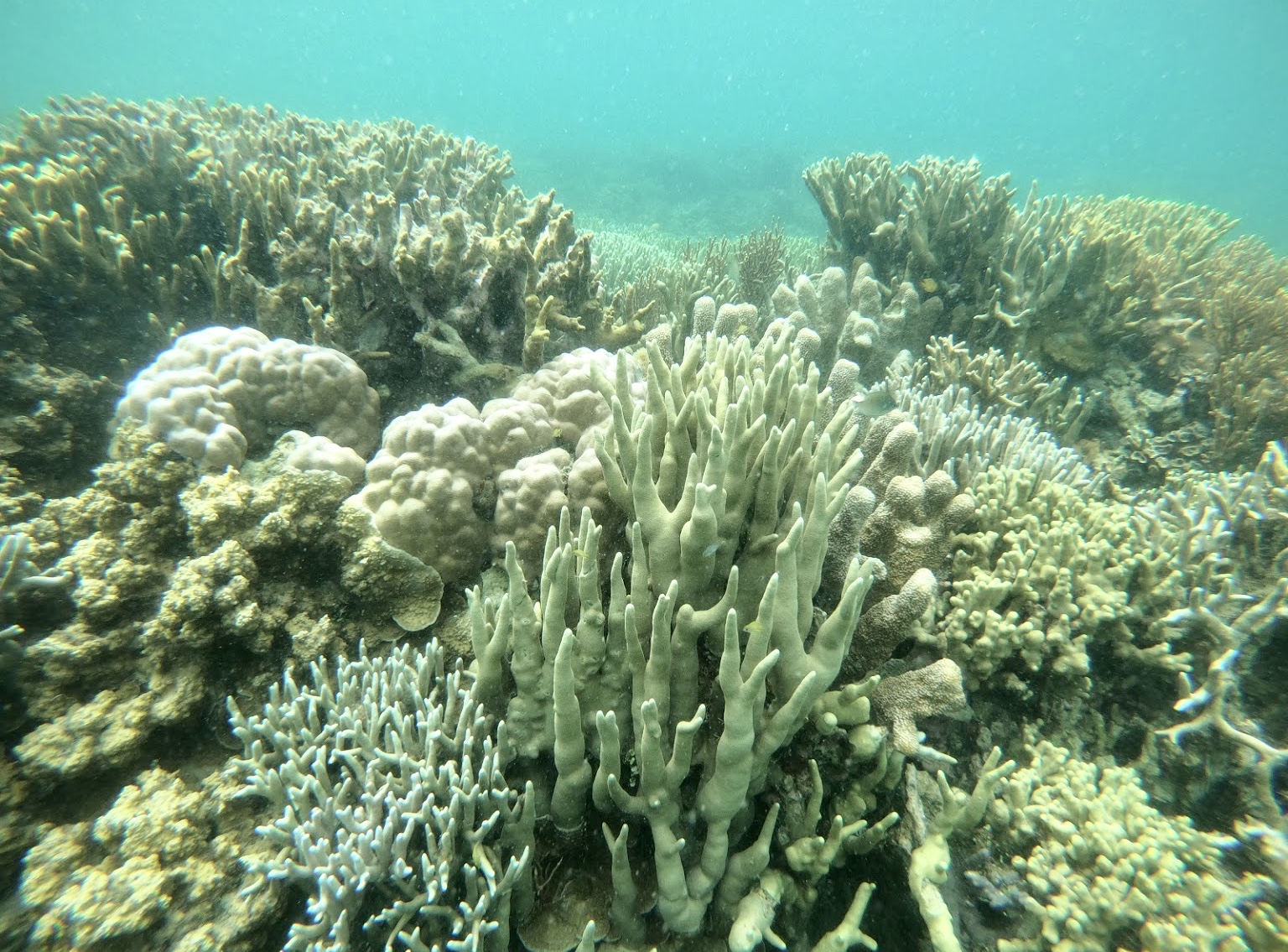

While the Samal reef gardens display colorful underwater vistas with its treasure of tropical marine life (which is why it is called the Island Garden City of Samal), some of the corals are not in good shape.

A survey conducted in the early 1990s yet by the Regional Fishermen’s Training Center in Panabo City at Sarangani Bay and Davao Gulf had shown that most of the shallow or inshore coral reefs “were totally damaged because they are exposed to greater pressure.”

But the destruction of coral reefs is rampant not only in Davao Gulf but in other parts of the country as well. In the late 1970s, the East-West Center in Hawaii sounded the alarm. At that time, the study disclosed that more than half of the reefs were “in an advanced state of destruction.” Only about 25% of live coral covers were in “good condition,” while only 5% were in “excellent condition.”

Nothing much has changed since then. In fact, 30% of the country’s coral reefs are reportedly dead, while 39% are dying. Reef Check, an international organization assessing the health of reefs in 82 countries, identified the coral reefs which are in “excellent condition” are the Tubbataha Reef Marine Park in Palawan, Apo Island in Negros Oriental, Apo Reef in Puerto Galera, Mindoro, and Verde Island Passage off Batangas.

“Nowhere else in the world are coral reefs abused as much as the reefs in the Philippines,” commented Don E. McAllister, who once studied the cost of coral reef destruction in the country.

On land, the ecosystem supports the greatest number of plant and animal species in the rainforest. In the sea, it’s the coral reef.

The corals most people have seen are actually the dried and bleached skeletons of soft-bodied animals that live in the warm, sunlit waters of tropical seas and look more like plants and rocks than animals.

The main part of the real coral is the polyp – the extraordinary flower-like animal with a tube-like body and finger-like tentacles. “Coral polyps get nutrition in two ways,” explains Lindsay Bennett, author of globetrotter island guide, Philippines. “They catch their food by means of stinging tentacles that paralyze any suitable prey – microscopic creatures called zooplankton – and also engage in a symbiotic relationship with zooxanthellae that live within the polyp structure.”

Science says coral polyps reproduce in two ways: asexually (by the division of existing individual polyps) and asexually (by combining egg and sperm from two different polyps). “This results in a free-swimming polyp that will be carried by ocean currents to find a new colony and commence a new reef,” Bennet writes.

Most of the coral reefs are found in the tropics of Cancer and Capricorn. The richest reefs are located in the so-called “coral triangle,” which spans eastern Indonesia, parts of Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, Timor Leste, and the Solomon Islands. Covering an area that is equivalent to half of the entire United States, it is considered “the epicenter for marine biodiversity.”

About 600 of the 700 or so corals known to man have been discovered in this region touted to be as “the Amazon of the Sea.” In the Philippines alone, more than 400 coral reefs are found.

There are three major types of coral reefs, according to Dr. Angel C. Alcala, former secretary of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). These are fringing type (those found on the edges of islands and which constitute 30% of the country’s coral reefs); the barrier type (best exemplified by the Dajanon Reef of Central Visayas); and the atoll (of which the Tubbataha and Cagayan Reef in the Sulu Sea are ideal examples).

Because of their structure, coral reefs serve as shelter to fishes and shellfishes. A single reef can support as many as 3,000 species of marine life. As fishing grounds, they are thought to be 10 to 100 times as productive per unit area as the open sea.

About 80-90 percent of the incomes of small island communities come from fisheries. “Coral reef fish yields range from 20 to 25 metric tons per square kilometer per year for healthy reefs,” Dr. Alcala said.

“Despite considerable improvements in coral reef management, the country’s coral reefs remain under threat,” said Dr. Theresa Mundita S. Lim, former director of the DENR’s Biodiversity Management Bureau.

“This means that fish and other marine life cannot be as productive as they were before,” said the International Marinelife Alliance (IMA) – Philippines. “Moreover, this will have a domino effect: fishermen will have fewer catches and lower income and there will be less fish and marine products for everyone.”

IMA identified the following as the primary culprits why coral reefs in this part of the world are on the brink of extinction:

Siltation: This is one of the major problems coral reefs are facing. Siltation is the settling of silt or sediment from dirty water. It is caused by soil erosion which is the result of deforestation in the uplands.

Destructive fishing: For almost three decades now, destructive fishing has been practiced by fishermen. Destructive fishing impairs the ability of coral reefs to produce fish and marine life. Moreover, the use of sodium cyanide and dynamite fishing in catching aquarium fish or live fish can damage coral reefs.

Pollution: Garbage and outflows from canals, ditches, and pipes dirty the ocean water. These prevent the sunlight from reaching underwater depths. Like plants, coral reefs need sunlight in order to stay productive and healthy.

But the Filipinos themselves are the primary culprit. “Life in the Philippines is never far from the sea,” wrote Joan Castro and Leona D’Agnes in a report. “Every Filipino lives within 45 miles of the coast, and every day, more than 4,500 new residents are born.”

The Philippines is now home to more than 100 million people. “Human activities are the major cause of coral reef degradation,” said a document that was released during the International Coral Reef Initiative held in Dumaguete City.

The pressure on human populations can be attested by visiting fishing barangays near a reef area. There are just too many fishermen, and they overfish the reefs. Even if they use non-destructive fishing gears, they still stress the coral reef ecosystem.

Dr. Robert Ginsburg, a specialist on coral reefs working with the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science at the University of Miami, also said human beings have a lot to do with the rapid destruction of reefs. “In areas where people are using the reefs or where there is a large population, there are significant declines in coral reefs,” he said.

The environment department urges all Filipinos to help save the country’s remaining coral reefs. “We must act now to save our remaining coral reefs, before it’s too late,” the DENR said in a statement published on its website.