Text by Henrylito D. Tacio

Photos by Gregory C. Ira

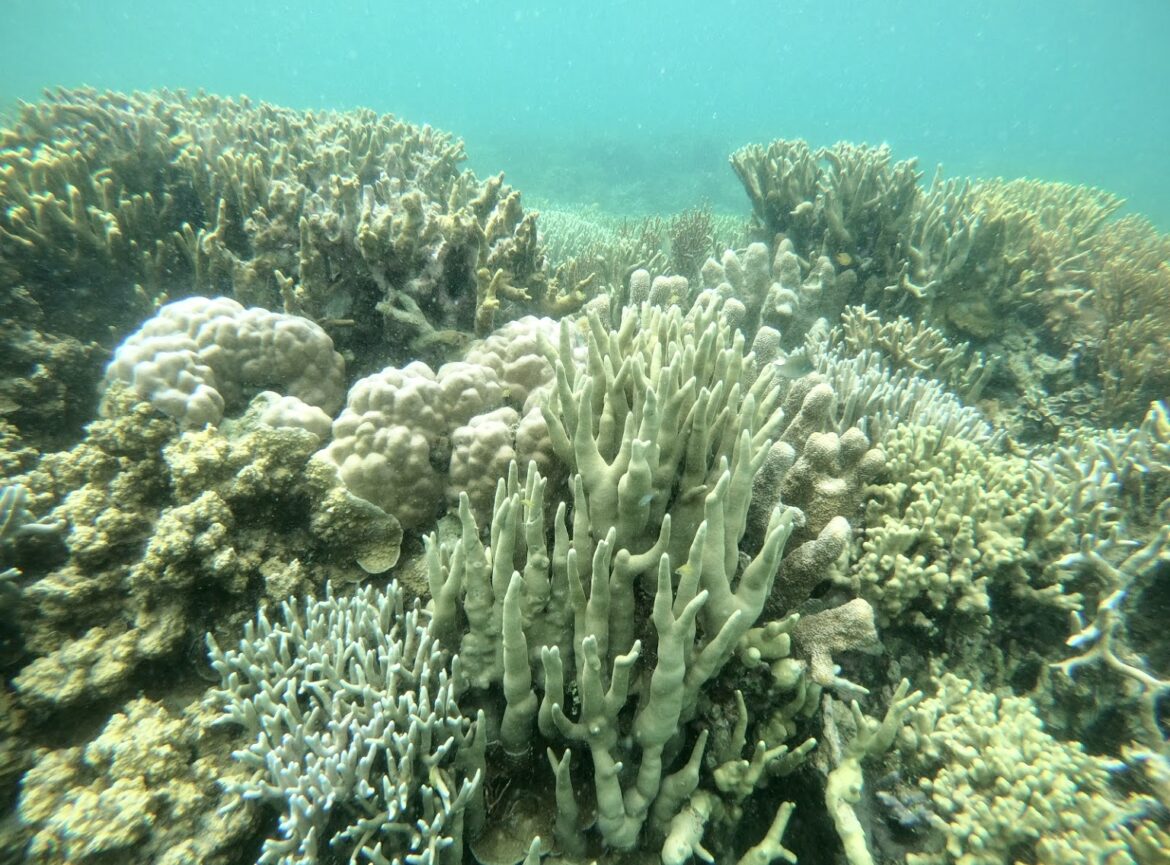

The Island Garden City of Samal, which is part of Davao Gulf, is not called an island garden because it has several vegetable and ornamental gardens but because of its colorful coral reefs. These reef gardens display colorful underwater vistas with their treasure of tropical marine life.

It’s no wonder why coral reefs are oftentimes called “Eden beneath the waves,” referring to the biblical Paradise described in Genesis.

“If you ever get the chance to dive, do it here; you will see what the best of the Davao Gulf has to offer,” says Darrell Blatchley, an American who has been living in Davao City almost half of his life and has dived Samal waters several times. “Fishing is strictly prohibited so the fish are plentiful and big. The fish are not afraid of you so they come in close as if they want to say hi!”

Coral reefs, the marine equivalent of rainforests, are biodiversity hotspots that contain an immense variety of life. Although occupying just 0.17 percent of the ocean floor, they are home to perhaps one-quarter of all marine species. “Essential life-support systems” necessary for human survival is how the World Conservation Union describes them.

But these coral reefs are teetering on the brink as a result of climate change. A new report, funded by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP), showed sharp declines in coral cover, corresponding with rapid increases in sea surface temperatures, “indicating their vulnerability to temperature spikes.”

This phenomenon is likely to increase as the planet continues to warm, according to the Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network, which collected data from more than 300 scientists from 73 countries over a span of 40 years, including two million individual observations.

The findings for the study were contained in the Sixth Status of Corals of the World: 2020 Report.

“Dynamic underwater coral cities support up to 800 different species of hard coral and are home to more than 25 per cent of all marine life,” the report said. “Soft corals bend and sway amongst the craggy mountains of hard corals providing additional homes for fish, snails and other marine creatures.”

Coral reefs harbor the highest biodiversity of any of the world’s ecosystems, making them one of the most biologically complex and valuable on the planet.

However, when waters get too warm, corals release their colorful micro-algae, turning a skeletal white color. Some glow by naturally producing a protective layer of neon pigments before they bleach.

“Bleaching can be thought of as the ocean’s version of the ‘canary in the coral mine’ since it demonstrates corals’ sensitivity to dangerous and deadly conditions,” the report stated.

Something must be done soon to save coral reefs from the brink.

“If we halt and reverse ocean warming through global cooperation, we give coral reefs a chance to come back from the brink,” the report pointed out. “It will, however, take nothing less than ambitious, immediate and well-funded climate and ocean action to save the world’s coral reefs.”

Ecologically-fragile coral reefs

Eden beneath the seas

The sad this is: the problem is also happening right here in our country, where more than 400 coral reefs are found. “Nowhere else in the world are coral reefs abused as much as the reefs in the Philippines,” deplores Don E. McAllister of the Ocean Voice International.

An analysis of more than 600 data sets showed that “excellent” reefs (live hard and soft coral cover above 75%) has reduced from 5.3% to 4.3% since the late 1970s. If hard corals alone are considered, only 1.9% of the reefs can be called “excellent,” with the average hard coral cover on all reefs at 32.3%, whereas it used to be much higher.

The decline is thought to be due primarily to destructive human activities.

Destructive fishing methods – ranging from dynamite blasts to cyanide poisons – are destroying vast areas of the reef. Fishermen blast reefs with dynamite to stun the fish. When fish float to the surface, fishermen scoop up large quantities at once. Heavily dynamited reefs produce only 2.7 to 5 metric tons per square kilometer per year compared to 30 metric tons for healthy reefs.

In many parts of the world, natural poisons have long been used in fishing without apparent damage. But such is not the case with sodium cyanide. In the Philippines, 80% of the exotic fish destined for pet shops and aquariums throughout Europe and North America are captured using cyanide. There is also a growing demand for live fish at upscale restaurants.

Another equally destructive fishing method is the muro-ami, a drive-in net used for fishing in coral reefs. It consists of a net bag with two long wings into which the schooling fish, like the dalagang bukid, are driven by the divers. The gear utilizes vertical scarelines weighed down by stones or chain links for creating a disturbance that drives out the fish from the coral reef into the net.

Coral mining has also depleted the country’s reefs. In fact, an estimated 1.5 million kilograms of corals are harvested annually as part of the international trade in reef products.

Also contributing to the destruction of coral reefs in the Philippines are sedimentation from erosion of soil from deforestation; the quarrying of coral reefs for construction purposes; pollution from industry, mining, and municipalities; and coastal population growth.

Coral reefs have existed for perhaps 500 million years, making them one of the oldest ecosystems on the planet. The creation of a reef can take centuries. Reefs are constructed by millions of minute animals called coral polyps, each of which lives inside a protective limestone skeleton.

The coral’s skeletons are amassed to form the foundation of a reef. The stony structures grow slowly, normally at a rate of 0.25 centimeters to 0.5 centimeters a year.

The Department of Environment and Natural Resources urges every Filipino to help save the country’s remaining coral reefs. “We must act now to save our remaining coral reefs, before it’s too late,” the DENR said in a statement published on its website.