By Henrylito D. Tacio

Photos by Gregory C. Ira

“Never bite the hand that feeds you,” so goes a familiar saying. When it comes to the ecologically-fragile coral reefs, some Filipinos are destroying the ecosystem that provides them fish, income and even protects them from natural calamities.

Despite their economic importance, coral reefs are being destroyed at an alarming rate.

“Although coral reefs have always been subject to natural disturbances – disease, predator outbreaks, and climatic disruptions such as hurricanes and the El Niño – natural damage is now being compounded by human-induced disturbances,” deplored Coral Reefs: Valuable but Vulnerable, a discussion paper circulated by the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF).

This is true in the Philippines, whose coral reef area – estimated at 26,000 square kilometers – is the second largest in Southeast Asia. A study conducted in 1997 showed only 4% of reefs in excellent condition (75% hard or soft coral cover), 28% in good condition (50-75% coral cover), 42% in fair condition (25-50% coral cover), and 27% in poor condition (less than 25% coral cover).

The Philippines is part of the Coral Triangle – so named because of its distinct triangular shape – a region in Asia that also includes Malaysia, Indonesia, Timor Leste, Papua New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands. Spanning these countries’ marine waters is nearly 73,000 square kilometers of coral reefs, which have been called “Eden beneath the waves.”

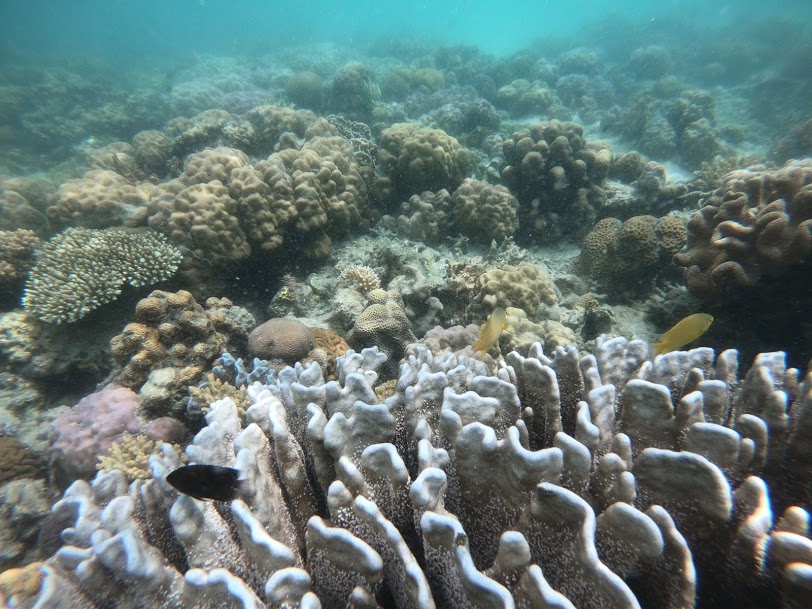

This magnificent area, often called the ‘Amazon of the Seas,’ is home to more than 3,000 species of fish – “twice the number found anywhere else in the world,” to quote the words of Suseno Sukoyono, executive chair of the Coral Triangle Initiative on Coral Reefs, Fisheries, and Food Security.

In terms of productivity, good coral reef areas can produce as much as 30 tons of fishery products per square kilometer in a year, according to Dr. Angel C. Alcala, a marine scientist who’s a recipient of the Ramon Magsaysay in 1992 for his pioneering efforts in restoring and conserving the coral reefs in the country.

Fish is the second staple food of Filipinos next to rice. On average, every Filipino consumes daily about 98.6 grams of fish and fish products, according to the Food and Nutrition Research Institute of the Department of Science and Technology.

The fishing industry provides employment to about one million Filipinos or around 3% of the country’s labor force. Unfortunately, these fishermen are among the annihilators of coral reefs through their destructive fishing methods.

“Many fishing methods, particularly the more modern ones, damage reefs,” the WWF reports. “Dynamite fishing is one of the most destructive and is still widespread. Sodium cyanide, which poisons and kills other reef life, is still commonly used to collect aquarium fish.”

Other damaging fishing techniques include spearfishing by scuba divers, fishing with close-meshed nets, and muro-ami.

“Muro-ami is especially common in the Philippines, where large numbers of small boys swim over the reef, pounding the corals with weights attached to long lines in order to drive the fish into a huge net,” the WWF notes.

Fishermen with big fleets, in most instances, overfish open seas. “Overfishing can have serious implications,” the WWF explains. “Many of the fish that are caught for food (examples: snapper, grouper, hogfish and triggerfish) are predators that feed on herbivorous fish and invertebrates, such as sea urchins, which play important roles on the reefs.”

Tourism is another source of income for those living near the seashores. “Coral reefs and sandy beaches are enormously popular with tourists, who turn up in droves to snorkel, dive, and explore reefs,” the WWF states.

In a way, tourism also abets the destruction of coral reefs. “Tourism affects reefs directly through damage inflicted on reefs by anchors, boat groundings, and tourists trampling on the corals,” the WWF stresses.

More importantly, coral reefs help the communities living the seashores from storms and wave action as they act as natural breakwaters. “If reefs become severely degraded, their ability to recover is markedly reduced and they may even have to be replaced using expensive engineering projects,” the WWF reminds.

In the Philippines, more than 40 million people live on the coast within 30 kilometers of coral reefs.

Other human activities that affect the coral reefs include deforestation, pollution, and economic development.

When people cut the trees, particularly those in the uplands, soil erosion ensues. Most of the eroded soils – in the form of silts – end up in the streams and shores. “Siltation occurs naturally as a result of terrestrial runoff and when waves and currents stir up bottom sediments,” the WWF says.

It must be recalled that when the forests surrounding Bacuit Bay were logged, erosion increased by up to 200 times the normal rate. As a result, five percent of the bay’s reefs died.

The WWF describes pollution as “one of the greatest threats to all marine environments” and “has a major impact on reefs.” The impact of nutrient enrichment (precursor of the “red tide” phenomenon) on reefs is fairly well understood and documented.

Aside from human activities, other causes of coral reefs destruction include typhoons, diseases, predator outbreaks, sea-level rise, and coral bleaching due to increased sea temperatures.

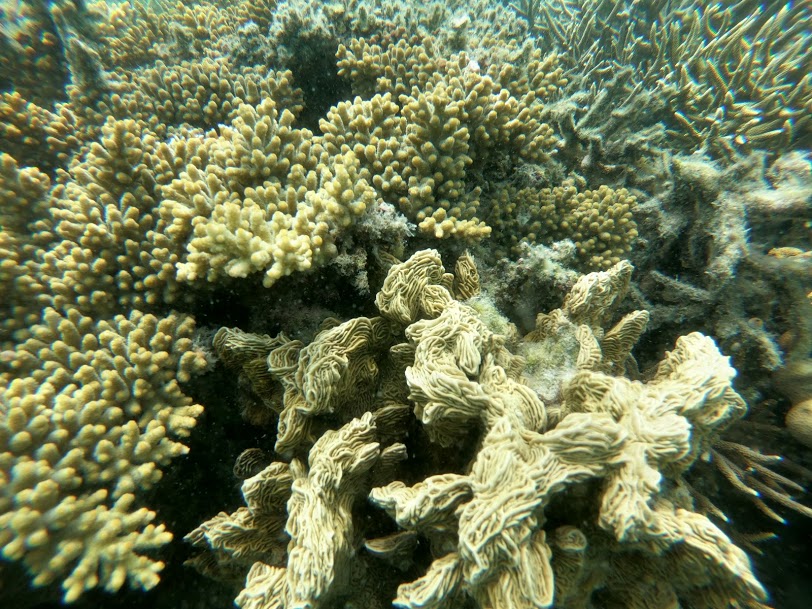

What most Filipinos don’t know that the corals they are familiar with are actually the dried and bleached skeletons of soft-bodied animals that live in the warm, sunlit waters of tropical seas and look more like plants and rocks than animals.

“The main part of the real coral is the polyp – the extraordinary flower-like animal and finger-like tentacles. Belonging to the phylum Coelenterata, corals comprised thousands of species,” the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR) explains.

“In colonies, polyps form the limestone structures which are known as coral reefs. These reefs are both beautiful and beneficial to man. These colorful, underwater ‘flower gardens’ teem with creatures found nowhere else on earth,” BFAR states.

Unfortunately, coral reefs are on the verge of extinction. “Despite considerable improvements in coral reef management, the country’s coral reefs remain under threat,” said Dr. Theresa Mundita S. Lim when she was the Biodiversity Management Bureau director of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources.

The Philippine government made and introduced many laws in an attempt to protect the natural environment on the islands and in the national territorial waters. But the government cannot do it alone; help from individuals are also needed to save the reefs from total annihilation.

“We are the stewards of our nation’s resources,” said Rafael D. Guerrero III, a national scientist with the National Academy of Science and Technology, “we should take care of our national heritage so that future generations can enjoy them. Let’s do our best to save our coral reefs. Our children’s children will thank us for the effort.”