Text by Henrylito D. Tacio

Photos from PCAARRD

More and more Filipinos are expected to experience hunger as the population continues to grow. In 1980, the Philippines was home to 48 million Filipinos. In 2000, the number swelled to 78 million. Today, there are more than 100 million people inhabiting the country.

Some years back, the Philippines was listed by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) as one of the 13 low-income food-deficit countries in Asia (“those that do not have enough food to feed their populations and for the most part lack the financial resources to pay for imports”).

The other twelve Asian countries – most of them thickly populated – were Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Laos, Maldives, Mongolia, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.

“In many developing countries, rapid population growth makes it difficult for agricultural production to keep pace with the rising demand for food,” wrote Don Hinrichsen in a report published by Population Reports. “Most developing countries already are cultivating virtually all arable land and are bringing more marginal land under cultivation.”

Jacques Diouf, at the time when he was the director-general of FAO, echoed the same concern. “Population growth continues to outstrip food availability in many countries,” he pointed out during the 1996 World Food Summit in Rome.

Food security

This alarms experts so much that the concept of food security came into existence. FAO defines it as a “state of affairs where all people at all times have access to safe and nutritious food to maintain a healthy and active life.”

People are told to experience a lack of food security when “either they cannot grow enough food themselves, or they cannot afford to purchase enough in the domestic marketplace.” As a result, “they suffer from micronutrient and protein energy deficiencies in their diets.”

Over the past ten years, malnutrition among Filipino children below the age of five has changed very little, observed Carin van der Hor, Country Director of Plan International.

“The reduction of child malnutrition has been alarmingly slow,” said Hor, who convened the Koalisyon Para Alagaan at Isalba ang Nutrisyon (KAIN) in a Hunger Summit organized by the National Nutritional Council some years back.

Citing the National Nutrition Surveys done in 2011, Hor said that children below five years old who are underweight remain at 20 percent while children who are below the average height-to-age ratio remain at 30 percent.

According to Senator Grace Poe, without sufficient nutrition, children’s motor development slows down, and their cognitive skills become stunted. “And this has a long-term negative impact on the development of our human capital. We cannot build the foundation of our future on emaciated bodies who are no longer in school. No nation on Earth can,” she decried.

Urban farming

The current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has enormously impacted the country’s economic and healthcare systems and also the nutritional and food security status of Filipinos, according to the Rapid Nutrition Assessment Survey (RNAS) by the Department of Science and Technology’s Food and Nutrition Research Institute (DOST-FNRI).

Survey results showed that six out of 10 or 62.1% of surveyed households reported they experienced moderate to severe food insecurity and that food security is highest in households with children (7 out of 10) and households with pregnant members (8 out of 10).

To solve this problem, some experts are recommending growing their own vegetables, particularly those living in the cities, who are greatly affected by hunger and malnutrition.

“Urban agriculture can be one of the most important factors in improving childhood nutrition, by increasing both access to food and nutrition,” wrote Brian Halweil and Danielle Nierenberg in their collaborative State of the World report for the Washington, D.C.-based Worldwatch Institute.

Fertilization

Harvesting

Another advantage: farms in the city can often supply markets on a more regular basis than distant rural farms can, particularly when refrigeration is scarce or during a rainy season when roads are bad.

Enriched Potting Preparation

There are several ways of raising vegetables in the garden. But Dr. Eduardo P. Paningbatan, Jr., a retired professor of soil science at the University of the Philippines at Los Baños (UPLB), has developed a better and easier method.

He called it Enriched Potting Preparation (EPP). Designed for communities with little space for gardening, it can provide urban families with healthy and pesticide-free vegetables and herbs. EPP is an easy and affordable way of growing plants right in the comfort of everyone’s home.

Among the vegetables which can be grown using EPP are lettuce, pechay, mustard, tomato, eggplant, ampalaya, okra, ginger, beans, kangkong, sweet potato, saluyot, spring onion, hot pepper, sweet pepper, Chinese celery, cucumber, kale, kinchay, and spinach.

For herbs, the following may be grown: basil, mint, parsley, sage, rosemary, thyme, wansoy, coriander, kaffir lime, tarragon, stevia, gotu kula, oregano, gynura, and mollocan.

According to the information bulletin published by the Philippine Council for Agriculture, Aquatic and Natural Resources Research and Development (PCAARRD), the materials needed for EPP are the following: 1.5-liter empty plastic soft drink bottle, potting medium, compost soil extract (CSE), and nylon string.

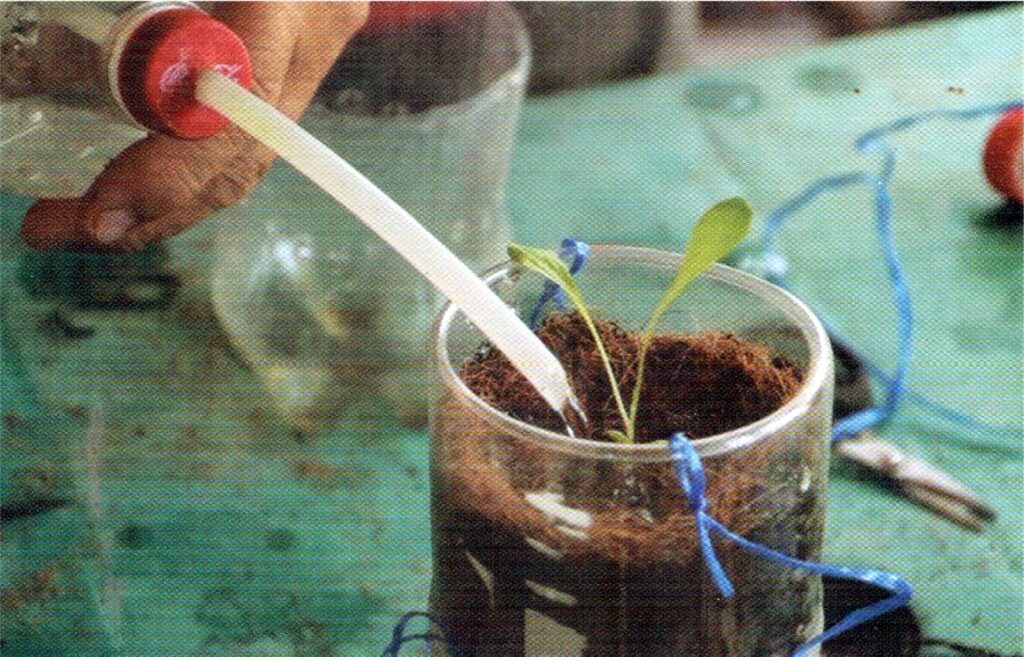

“Cut the plastic bottles in half,” PCAARRD instructs. “Put small holes on the sides of both top and bottom half of the bottle for aeration and drainage of excess water. Place the potting medium inside the inverted top half with the bottle cap. Use the bottom half as a stand for the top half to collect and reserve excess water for plant’s reuse.”

Now, it’s ready for planting. “Sow two or more seeds and cover with one millimeter of the potting medium. Remove the upper part and wet the potting medium by dipping the plastic bottle container into a pail of water.

“Put back the container by putting the bottom part on top of the soil surface. Place the EPP in a shaded area until seeds germinate, then place it where seeds can receive morning sunshine. If needed, transplant extra seedlings to other EPP. Place EPP where plants can receive at least two hours of full sunlight,” the PCAARRD instructs.

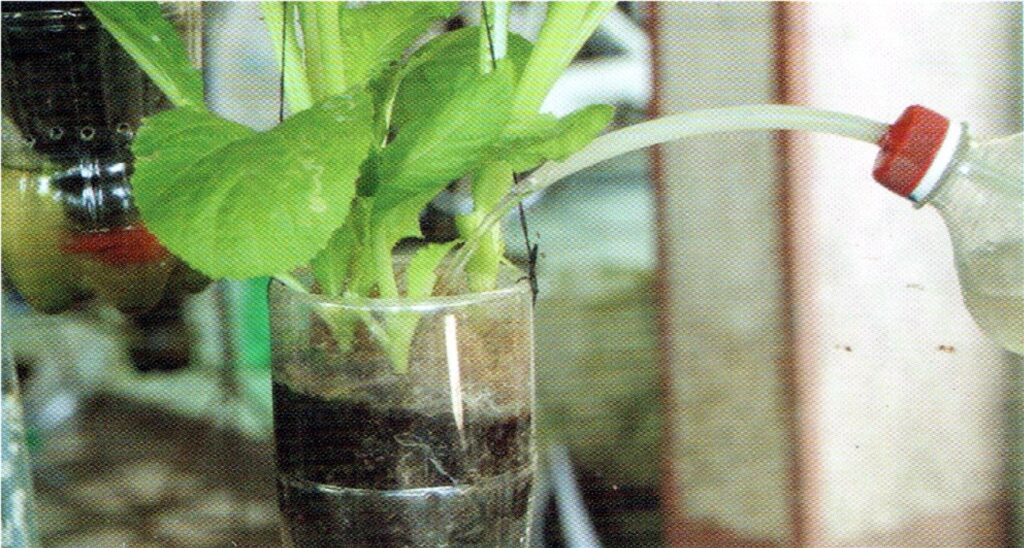

On watering, the PCAARRD notes: “Water the plants three times a week for seedlings or once a day for mature plants by dipping the EPP vessel into a pail of water or by sprinkling until the soil is fully wet.”

Like most crops, the EPP plants also need fertilizer. “Dilute CSE in a ratio of five tablespoons of CSE to one liter of water,” the PCAARRD says. “Water the plants with about 100 milliliters of the diluted solution once a week during seedling stage and twice a week as the plant matures.”

For pest control, the PCAARRD suggests dipping the whole EPP plant into a clean pail of water for 15 minutes to one hour, depending on the severity of the pest infection.

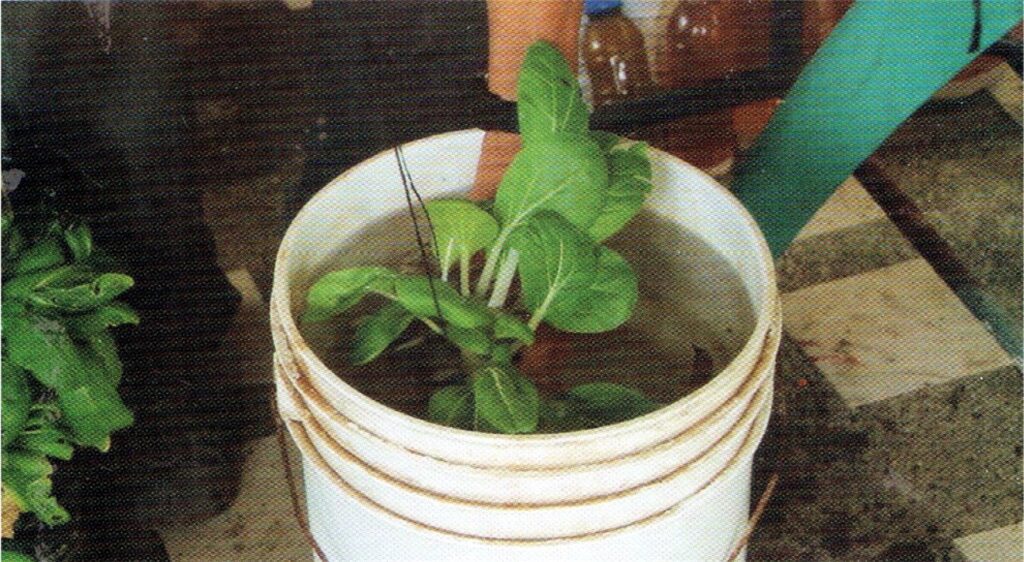

You don’t have to harvest immediately once they mature. For green leafy vegetables like pechay and lettuce, for instance, you can harvest the leaves using scissors. Just leave the younger leaves and let them grow until ready for the next harvest.

There are several advantages of raising vegetables in the EPP way. For one, plants are easier to care for and tend. For another, there is a continued harvest of fresh, succulent leafy vegetables. More importantly, vegetables can be grown six cycles a year.

Vegetable consumption

Eating vegetables has several advantages, too. Studies show that those who eat more vegetables and less meat are most likely to live longer than their counterparts. According to a new study, people who limit how much meat they eat and stick to mostly fruits and vegetables are less likely to die over any particular period of time.

“I think this adds to the evidence showing the possible beneficial effect of vegetarian diets in the prevention of chronic diseases and the improvement of longevity,” Dr. Michael Orlich, the study’s lead author from Loma Linda University in California, was quoted as saying by Reuters.

Previous research done in the United Kingdom suggested that vegetarians are one-third less likely to be hospitalized or die from heart disease than meat and fish eaters. “We’re able to be slightly more certain that it is something that’s in the vegetarian diet that’s causing vegetarians to have a lower risk of heart disease,” said Dr. Francesca Crowe, who led the study at the University of Oxford.

“If people want to reduce their risk of heart disease by changing their diet, one way of doing that is to follow a vegetarian diet,” Dr. Crowe added.