HEPATITIS B: UNDERSTANDING THE HIDDEN EPIDEMIC

Text by Henrylito D. Tacio

Photos: Getty Images

Twenty-five-year-old Michelle was totally devastated when her obstetrician told her she had hepatitis B. She was not ready to receive the bad news as she was in the ninth month of her first pregnancy.

“Your family physician sent me over copies of your blood tests,” her obstetrician said. “As she told you, the tests show that you carry the hepatitis B virus. Fortunately, the tests of your liver function are totally normal, and there’s no indication that there’s been any significant damage to your liver.”

“That’s great,” she answered sarcastically. “But most of my family members have died of liver disease or liver cancer. And what about my baby?” she wondered. “Will I give my baby the disease, too?”

Michelle is not alone in her dilemma. Worldwide, hepatitis B is one of the major diseases of mankind and is a serious public health problem. In Southeast Asia, more than half the population becomes infected with the virus. In the Philippines, around 8.5 million Filipinos are chronically infected with hepatitis B virus, according to the estimates released by the World Health Organization (WHO).

“Hepatitis B is endemic in most countries in Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific region with carrier rates between 5 and 35 percent except in Australia, New Zealand and Japan where the average carrier rate is 2 percent,” disclosed Prof. Ding-Shinn Chen, a medical professor and head of the gastroenterology division at the Department of Internal Medicine in the National Taiwan University Hospital.

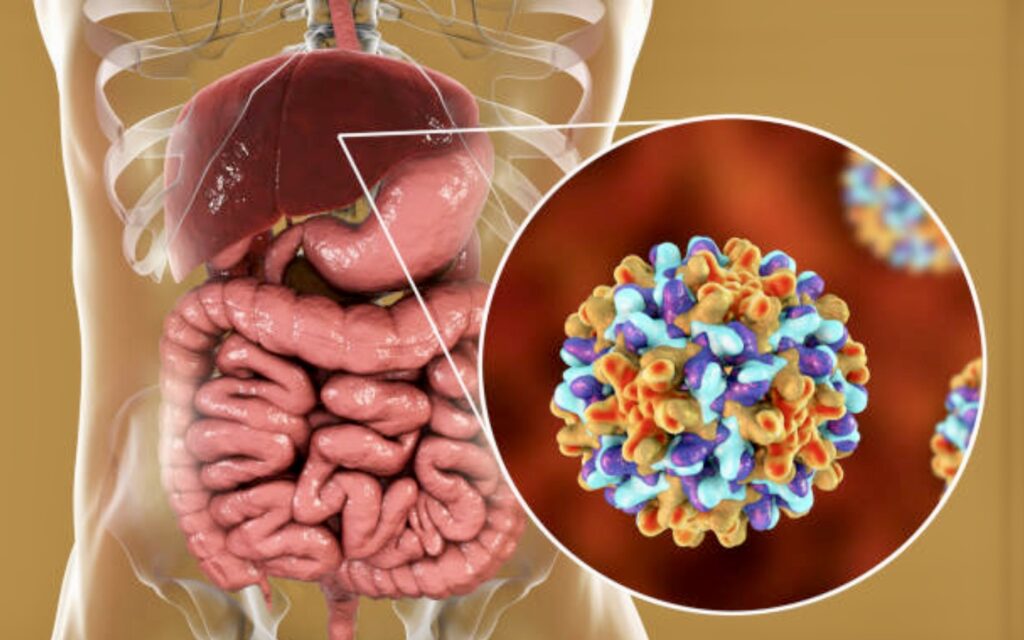

The word hepatitis simply means “inflammation of the liver.” Oftentimes, doctors use it to refer to the diseases caused by hepatitis viruses. If a physician tells a patient, “You have hepatitis,” he means that the person has a viral disease caused by a virus that attacks the liver, and not necessarily that he has an inflamed liver.

So far, medical scientists have discovered six different kinds of hepatitis: A, B, C, D, E, and G. A different virus causes each of these. Five types cause disease in the liver while one (hepatitis G) lives in the blood without causing any apparent illness. All five disease-carrying viruses are responsible for more than 98 percent of cases of viral hepatitis. The most important among the five viruses in terms of public health is the hepatitis B virus (HBV).

Unknowingly, “hepatitis viruses cannot live outside a cell,” points out Professor John S. Tam of the Department of Microbiology at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. “They only come alive when they are given the right conditions such as the necessary nutrients from inside a cell. At room temperature, they do not last very long – maybe 10 minutes. Once the blood dries, infectivity decreases.”

Like most hepatitis viruses, HBV is all too easy to catch. It is more common than the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the microorganism that causes the dreaded Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS), and far more infectious – HBV is 50-100 times more infectious than HIV. “While 90 percent of the people who get hepatitis B recover spontaneously with their body’s defenses, the 10 percent who maintain the infection for six months or longer and who do not produce an effective antibody response are considered chronic carriers,” explains Dr. Ernesto Domingo, head of the Liver Study Group of the University of the Philippines in Manila.

A small percentage of these chronic carriers will serve 30-40 years later, ultimately developing cirrhosis (scarring of the liver) or liver cancer. “Hepatitis B virus is the most common cause of liver cancer around the world,” says Professor Mei-Hwei Chang, chairman of the Department of Pediatrics at the National Taiwan University Hospital in Taipei. “Although hepatitis C virus is the most prevalent cause of liver cancer in some countries where HBV infection is not prevalent, HBV is still the most prevalent cause worldwide.”

The HBV may be found in blood, semen, vaginal fluids, tears, and saliva. It is transmitted the same way as HIV. That is, through sexual intercourse (vaginal, oral, or anal), use of contaminated needles, unsafe blood transfusion, and from mother to child.

There are reports that HBV may also be transmitted by puncturing the skin with sharp instruments – such as those used for acupuncture, dental, and medical procedures, even for ear piercing and manicures – that have been contaminated. “But the most effective means of transmission is sexual contact other than kissing,” says Dr. Dominic Garcia, an infectious specialist based in Manila. “The scary thing is that a lot of people don’t know they have it.”

Intravenous drug users are among the most susceptible people to HBV “because of their exposure to other people’s blood,” points out Prof. Tam. Also, high risks of developing the disease include institutionalized children or adults, sexually active people, and men-having-sex-with-men, among others. People with kidney diseases that require dialysis and those undergoing treatment of leukemia are also at high risk of contracting HBV.

In some developing countries like the Philippines, Indonesia, and Vietnam, newborns may be infected if their mothers are chronic carriers. “HBV is transmitted mainly from mother to child during birth,” explains Prof. Tam. “When infants get infection early in life, the chance of them being a carrier, if not controlled, can be as high as 95 percent.”

The United Nations health agency estimates that 400 million people are now infected with HBV and that the number of new infections will keep increasing until vaccination of infants is a universally established practice.

Contrary to common belief, there are no documented cases of hepatitis B being transmitted by a person being breathed on by someone with the illness, catching it from an insect bite (mosquito, for instance), or getting it through contaminated water.

What about kissing? “Although hepatitis B virus can be detected in very low concentration in tears and saliva, both are not important routes of transmission for hepatitis B virus. They can be infectious only when infected persons’ gastrointestinal tract or skin have wound. Therefore, the chance of infection though this route is very low,” says Dr. Chang. The most high-risk condition for kissing to transmit HBV is due to oral wounds.

If you care to know, hepatitis B is not transmitted casually. As such, the virus cannot be spread through sneezing, coughing, hugging, or eating food prepared by someone who is infected with HBV, according to the UN health agency. Also, you cannot get HBV from mosquitoes. Prof. Tam explains: “All viruses which are transmitted by a mosquito must go through a replication before sufficient viruses are available for infection. HBV does not grow in mosquitoes.”

“The hepatitis virus is very durable,” points out Dr. Alan Berkman, author of Hepatitis A to G: The Facts You Need to Know About All the Forms of This Dangerous Disease. “It can remain infectious on environmental surfaces for at least a month if left at room temperature. Most people who get it fight off the infection by themselves, but the virus antibodies will be present in their blood for the rest of their lives.”

The WHO says that the incubation period of HBV takes a long 45 to 180 days, usually without any manifestations or symptoms. Thus, people infected with hepatitis B may not even realize that they have it until the latter stages of the disease. And even when symptoms are present, they are vague, often mimicking other, less life-threatening diseases.

“Sometimes, people infected with HIV have what looks like the flu, with symptoms including loss of appetite, nausea and vomiting, fever, and weakness,” explains Dr. Berkman. “They may also develop symptoms more directly related to their livers: abdominal pain, dark urine, and yellowing of the eyes and skin. That kind of hepatitis B infection is usually harmless, even if it can be a little unpleasant for a period of time.”

But, as stated earlier, about 8-10 percent of people who are infected develop chronic hepatitis B. “There are two forms of hepatitis B, one acute and the other chronic,” says Dr. Berkman. The acute disease is very unpleasant, but if you recover from it, you are likely to be immune from then on. Unfortunately, sometimes the acute disease progresses to the chronic form. A blood test can determine if you have the acute form of the disease.”

What happens to a person infected with HBV? “When a person becomes infected by hepatitis B, the virus travels to the liver where it enters individual liver cells,” said Prof. Nancy Leung, consultant, and honorary associate professor and chief of hepatology at the Prince of Wales Hospital in the Chinese University of Hong Kong. “Here, it replicates and may reenter the bloodstream or reinfect other liver cells. Symptoms of initial infection with hepatitis B result from the body’s attempt to defend itself against infection.

Prof. Leung continues: “Those individuals with the most severe of symptoms are therefore most likely to eliminate the virus from their body while those with no symptoms or have very mild complaints – typically children – are most likely to retain the virus and become long-term carriers.”

Prof. Leung added that the HBV might remain in some individuals after the initial infection, and the patients are said to be chronic hepatitis B carriers when part of the surface of the virus remains in the blood for more than six months. “The result of long-term carriage of the HBV is continuing inflammation of the liver, which may lead to serious liver damage and cancer,” she said.

Liver cancer is almost always fatal and usually develops between the age of 35 and 65 years of age, when people are maximally productive and are trying to raise their own children. It occurs more commonly among Asians. In Singapore, for instance, liver cancer is the third most common cancer and the second most common cancer among males. “The risk of liver cancer increases with smoking and consumption of alcohol,” says Prof. Chang.

Like the dreaded AIDS, hepatitis B is incurable. However, it can be prevented with active or passive immunization. In active immunization, the person develops long-term protection against a new infection as a result of the production of antibodies. These antibodies may develop either naturally when he or she is infected with HBV or artificially after receiving a vaccine.

In passive immunization, the person develops short-term protection against a new infection. Passive protection can develop when an unborn child receives antibodies from the mother, or the newborn baby gets antibodies from colostrum, the first breast milk secreted by the mother after delivery, or when a vaccine containing antibodies is injected into the body.

There are two types of vaccines currently available for active immunization against hepatitis B. One is the recombinant hepatitis B vaccine, which offers long-term protection against infection. The vaccine, synthesized from yeast cells, provides about 90 percent protection against hepatitis B. Example of this vaccine is Interferon (sold as Intron A), which boosts the immune system of the patient to kill the hepatitis virus. However, it is only effective in 40 percent of patients. Injections have to be done thrice a week for six months. Another is Lamivudine (sold as Epivir-HBV, Zeffix, or Heptodin), an oral antiviral drug that directly inhibits HBV. The drug must be taken daily for one year.

The other vaccine currently used is hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG). The vaccine, which is as safe and effective as the recombinant hepatitis B vaccine, is a preparation made from human blood plasma that contains a significant amount of the antibody for the hepatitis B virus.

“Immunization against hepatitis B is currently recommended for all newborns and for people at high risk of developing the infection,” says Dr. Rakesh Aga, gastroenterology expert at the Indraprastha Apollo Hospital in New Delhi. “One injection of the hepatitis B vaccine is given in the muscles of the upper and outer parts of the arm at birth, at the age of one month and at six months.” A booster dose is recommended when the child turns five.