Text and photos by Henrylito D. Tacio

Additional photos by Gregory C. Ira

In his book, Depletion of the Forest Resources in the Philippines, Singaporean author Ooi Jin Bee wrote: “The once forest-rich Philippines is well on its way to becoming the first country in Asia to achieve the dubious distinction of complete deforestation by the year 2000.”

Eighteen years later, the Philippines still have some forests left. But catastrophes – as a result of denudation – continue unabated: flooding, drought, water crisis, food insecurity, and biodiversity loss.

“The root cause is the denudation of our forests,” commented Jethro P. Adang, the director of the Mindanao Baptist Rural Life Center, a non-government organization based in Kinuskusan, Bansalan, Davao del Sur. “This is a sin of the past that we are paying now.”

Rev. Harold R. Watson, a former American agriculturist who had been helping the locals when he was still assigned in Mindanao, agreed. “When man sins against the earth, the wages of that sin is death or destruction,” explained the recipient of the Ramon Magsaysay Award in 1985 for peace and international understanding. “This seems to be the universal law of God and relates to all of God’s creation. We face the reality of what man’s sins against the earth have caused. We are facing not a mere problem; we are facing destruction and even death if we continue to destroy the natural resources that support life on earth.”

It is impossible to exaggerate the ecological debacle threatening the Philippines. More than 90 years ago, the Philippines was almost totally covered with forest resources distributed throughout the 30 million hectares. In the 1950s, only three-fourths of the archipelago was covered with forest, according to the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). By 1972, the figure had shrunk to half – and by 1988, the only quarter was wooded, and just one tiny fraction of this was virgin forest.

The Rome-based United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) said about 7,665,000 hectares of the country are forested. Between 1990 and 2010, the country lost an average of 54,750 hectares per year.

Logging – whether legal or illegal – is one of the primary culprits of the fast disappearance of the country’s forest resources.

“Logging is most ecologically destructive in the mountains,” wrote multi-awarded science journalist Alan Robles in an article circulated by the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ). “It is next to impossible to replant trees on rocky mountain sides once their thin skin of topsoil has been washed away.”

The tragedy that happened in the cities of Iligan and Cagayan de Oro a few years back was proof of the havoc caused by excessive mountain logging. Floods and landslides buried more than 1,000 people, and a thousand more were missing.

Cutting and processing of the logs cut from the forest constitute a big industry. But it creates an environmental hazard in areas where it is done. “The destructive of logging stems from its unsustainable nature,” Robles explained. “It is an extractive industry that destroys forest resources at a much faster pace than they can be replaced by nature’s regenerative capacity.”

Remnant of deforested area

Deforestation

In his article, Robles further wrote: “Even reforestation (which most loggers don’t bother to do after they have mowed down their concessions) doesn’t restore the ecological balance and diversity because the process of logging itself destroys so much. Loggers bulldoze roads by cutting a swath through the jungles. And when the trees are cut, they are dragged across the fragile undergrowth, destroying saplings and other vegetation.”

Singaporean author Ooi Jin Bee pointed out kaingineros (swidden or slash-and-burn farmers) as the primary culprit of the fast disappearance of the country’s forest cover. When he computed the rate of annual deforestation of both virgin and secondary growth forest due to kaingin from 1980 to 1985, he found out that kaingin accounted for at least 50% of the forest destruction in the country.

Other causes of deforestation in the country include mining operations, forest fires, volcanic eruptions, geothermal explorations, dam construction and operations, fuelwood collection, and land development projects (construction of subdivision, industrial estates, and commercial sites).

The country’s surging population has likewise contributed to the problem. At least a fourth of the total population lives in the upland areas, where most trees are located. Most of them practiced kaingin farming. “These migrant farmers attack virgin forest lands to cultivate the rich soil, which they quickly deplete,” observed Watson. “Then, they move on, looking for more. One day, there is no more.”

More often than not, deforestation is often equated with calamities like landslides and flash floods. In its editorial, Philippine Daily Inquirer deplored: “In just one decade, 2000 to 2010, 27 floods and 17 landslides occurred, affecting about 1.6 million people each year and destroying crops and infrastructure worth tens of million pesos a year. In all these floods and landslides, deforestation was a major factor. Bald mountains, depleted forests and barren watersheds caused rainwater to flow down and flood the plains.”

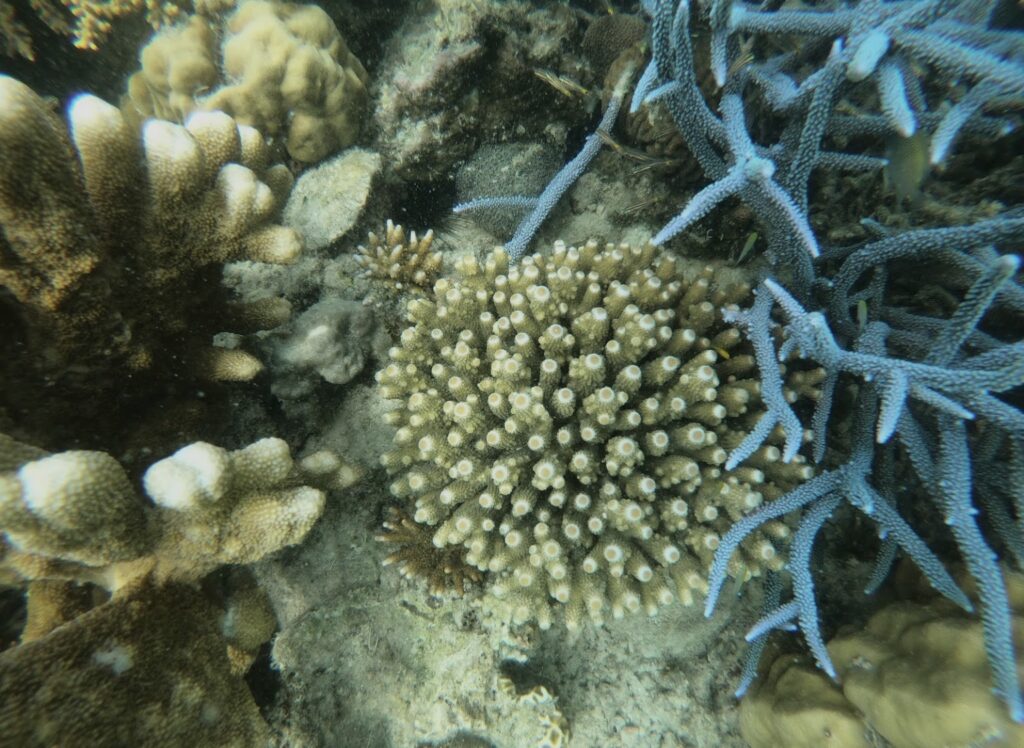

But there’s more to deforestation than just flash floods and landslides. What happens to the uplands also happens to the coastal areas. And it is the latter that suffers the most. That’s what happens to the coral reefs, which are on the verge of extinction, as deforestation continues unabated in the higher grounds.

“When trees are cut and human beings are affected as a result of flash floods, people rallied against deforestation. But like forests, coral reefs are also suffering the same magnitude of destruction,” explained Dr. Bernhard Riegel, associate director of the National Coral Reef Institute in the United States.

But how come deforestation helps destroy coral reefs, which are touted as the rainforest of the sea? One of the consequences of cutting trees, particularly in the uplands, is soil erosion. According to the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), about a billion cubic meters or about 200,000 hectares of one-meter deep topsoil are lost every year due to erosion.

“No other soil phenomenon is more destructive worldwide than is soil erosion,” wrote Dr. Nyle C. Brady in his book, The Nature and Properties of Soils. “It involves losing water and plant nutrients at rates far higher than those occurring through leaching. More tragically, however, it can result in the loss of the entire soil.”

When soil erodes from fields, it does not simply move to another spot on the farm. Much of it ends up in streams, rivers, lakes, and coastal areas. Sedimentation, as a result of deforestation in the uplands, is said to be the most important single cause of coral reef destruction.

“The biggest culprit is perhaps forest denudation,” pointed out the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR), a line agency of the Department of Agriculture.

“When loggers, kaingineros, firewood gatherers, and charcoal makers cut down trees and burn underbrush,” the BFAR explained, “they leave the soil of the mountainsides bare and defenseless against strong wind and rain.

“During rains, runoff carries eroded soil down to the rivers that deposit it in the sea,” it further said. “This siltation smothers reefs and kills or drives away to inhospitable areas the fishes that feed and shelter among the corals.”

Deforestation is also cited as one of the perpetrators of climate change. Intact forests produce a substantial portion of the earth’s oxygen and remove carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas, from the atmosphere. Cutting and burning trees contribute 25% of the world’s global warming gasses, studies show.

In recent years, corals are exhibiting a new kind of degradation: massive bleaching. “When subjected to extreme stress, (the corals) jettison the colorful algae they live in symbiosis with, exposing the white skeleton of dead coral beneath a single layer of clear living tissue. If the stress persists, the coral dies,” explains John C. Ryan of the Washington, D.C.-based Worldwatch Institute.

Coral reefs (Photo by Gregory Ira)

Coral reefs (Photo by Greg C Ira)

Bleaching has been cited as “the worst threat to the survival of coral reefs.” “While its causes are not known, bleaching appears when ocean temperatures are abnormally high,” Ryan writes.

But the biggest threat still comes from deforestation. As the recent study published in Nature Communications puts it: “Curbing sediment pollution to coral reefs is one of the major recommendations to buy time for corals to survive ocean warming and bleaching events in the future. Our results clearly show that land use management is the most important policy action needed to prevent further damage and preserve the reef ecosystem.”

The researchers of the study found that mitigating erosion on land is more important to saving coral reefs right now than even addressing climate change. “Without addressing the current issues, we won’t have living coral reefs to try and save from warmer ocean temperatures,” they pointed out.

Why should Filipinos be concerned about the vanishing coral reefs? Fish, like rice, is the staple food of Filipinos. An estimated 10-15 percent of the total fisheries come from coral reefs. About 80-90 percent of the income of small island communities comes from fisheries. “Coral reef fish yields range from 20 to 25 metric tons per square kilometer per year for healthy reefs,” says Dr. Angel C. Alcala, the former environment secretary.

The Philippines, whose coral reef area – estimated at 26,000 square kilometers – is the second largest in Southeast Asia. The Inventory of the Coral Resources of the Philippines in the 1970s found only about 5% of the reefs to be in excellent condition, with over 75% coral cover (both hard and soft).

Another study conducted in 1997 showed only 4% of reefs in excellent condition (75% hard or soft coral cover), 28% in good condition (50-75% coral cover), 42% in fair condition (25-50% coral cover), and 27% in poor condition (less than 25% coral cover).

“Despite considerable improvements in coral reef management, the country’s coral reefs remain under threat,” said Dr. Theresa Mundita S. Lim, former director of the Biodiversity Management Bureau of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources.

The Philippine government made and introduced many laws in an attempt to protect the natural environment on the islands and in the national territorial waters. But the government cannot do it alone; help from individuals is also needed to save the reefs from total annihilation.

“We are the stewards of our nation’s resources,” said Rafael D. Guerrero III, an academician with the National Academy of Science and Technology, “we should take care of our national heritage so that future generations can enjoy them. Let’s do our best to save our coral reefs. Our children’s children will thank us for the effort.”