Text by Henrylito D. Tacio

Photos: US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Dengue is a water-borne disease, and so the best possible solution to it might be in the water, too. “It’s simply a water in versus water out issue,” explains Dr. Richard T. Mata. I came to know Dr. Mata a few years back when I attended a seminar convened by the Department of Science and Technology at Marco Polo Davao.

He is an unassuming physician who caught my attention because of his “invention” in using computers instead of writing down prescriptions to patients.

A few weeks later, after that encounter, I found out he is a pediatrician who has a clinic in Panabo City, which has been plagued by dengue every now and then. “Caring for dengue patients has become almost an everyday task,” he admits. It was just a matter of time that he learned so many things about dengue.

Today, he is known for his anti-dengue advocacy. In fact, he makes his own website – www.solving-dengue-fever.com, which he updates regularly – to educate thousands of people around the world on the truth about dengue fever.

“It’s about hydration,” pointed out Dr. Mata. What he is referring to is the process of providing an adequate amount of water to the body tissues of a dengue patient. “In dengue, our blood vessels will appear to have some holes through it and so the fluid, which we call as plasma, leaks out and causes dehydration among patients,” he explained.

But it’s not only water, which plasma contains, that comes out but platelets as well. “This is the reason why the platelet decreases because it comes out of the holes of the blood vessels,” he said. Dr. Mata said that just like an ordinary wound, the blood vessel holes heal within six days.

“That’s why in dengue, the platelet is observed to have decreased until the sixth day of fever and from there, the platelet starts to increase again as the holes begin to close,” he said.

What really kills a person with dengue is not due to low platelet counts but dehydration. It occurs when a person loses more fluid, and his body doesn’t have enough water and other fluids to carry out its normal functions.

“Dehydration is the killer,” he declared, “low platelet is only secondary.” Dr. Mata pointed out that even if the platelet continues to decrease each day for as long as the patient is fully hydrated with dextrose and oral fluids, the patient is safe.

“The best indication the patient is fully hydrated is that he keeps on urinating with an interval of one to three hours,” he said. “If the patient does not urinate for more than 5 hours and looks very weak and sleepy, he can be in a brink of either hypotension (low blood pressure) or kidney failure.”

To further explain the dengue problem, he talked of another disease called idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP). “This is a disease where the child has a low platelet from weeks to years in duration,” he said. “I have some patients who have this disease. Some will have platelets as low as 10 or less, but once you see them you can’t believe that their platelets are that low. They are still playing and active despite the fact their blood platelet status is low.”

Dr Mata receiving an award

Dr Mata doing his lecture

The ITP patients may have low platelet count, “but they are not suffering from dehydration, which is not part of ITP but it is present in dengue cases.”

According to him, “if an ITP patient will develop severe diarrhea and will not be brought to the hospital, he or she will develop severe bleeding just like dengue.” In simpler terms, it’s the fluids that matter. “The low platelet will only cause harm if the patient is dehydrated,” Dr. Mata declared.

Here is his explanation: “The truth is that even if the platelet of a dengue patient is low, but as long as the patient is properly hydrated, the patient will not give us any problem. Therefore we need to bark at the right tree, the right tree is the fluids and not the platelets.”

In his experience, Dr. Mata discovered that dengue comes in various types.

Not all dengue cases are created equal. “Some are very mild and some are very strong,” he said. “To understand it, we still need to look at the degree of fluid dehydration. The ones that are mild are those not so dehydrated and those that are toxic are those severely dehydrated.”

Now, going back to his “theory” about those holes in the blood vessels of dengue patients, thus causing the fluids and platelets to sip out.

He classified dengue into mild, moderate, severe, and very severe.

“What made these dengue types different from each other are simply the sizes and the amount of the holes it gives the blood vessels of the patient,” he explained. To illustrate, he used a plastic bag filled with water. “If I use a needle and put a few tiny holes through it, will the water inside drain immediately?” he asked. “Certainly not. This is therefore the mild one.”

According to him, drinking lots of fluids can easily compensate for the minute loss. “That’s why you can hear dengue patients who survived without even being admitted in the hospital; they, fortunately, have small holes,” he said. “But what if I use a nail and place holes in the plastic bag? Of course, the leaking will be faster and sooner than you expect.

“If only all dengue patients come in with tiny leaks in their blood vessels then everything will be easy and not messy,” he said.

It is in those having big holes that water replacement is a necessity – and immediately. “It will just be a matter of time the patient will dehydrate that can cause the kidney to be damaged and result in other organ failures,” Dr. Mata said.

This is the reason why dengue is very different from diarrhea, which is also a disease of dehydration.

“In diarrhea you can easily estimate the amount of fluids that goes out with stool and thus estimate the amount that is needed back to compensate for the loss,” he said. “In dengue, you cannot see the fluid coming out literally because the plasma leakage only brings the fluids outside the blood vessels but still inside the body.”

This is what Dr. Mata believed: “The majority of dengue deaths are caused by lack of fluids that come in compared to the amount of fluids that come out of the blood vessels.”

There are those who believe that other dengue deaths are due to too much fluid that causes congestion in the lungs. His answer: “Congestion in dengue is caused by lack of fluids in the first days of illness causing kidney failure which results in the inability of the body to urinate. The outcome: congestion. Thus, it is still dehydration to begin with. Solving this balance will solve dengue.”

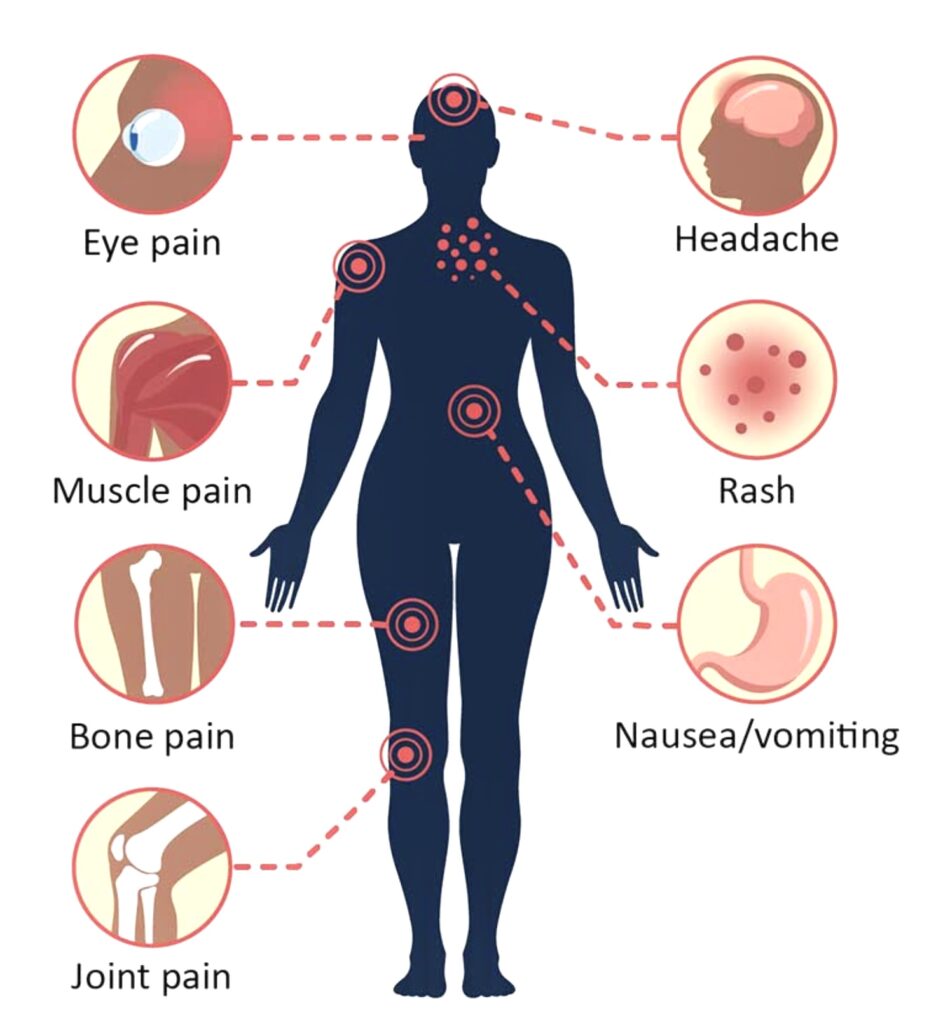

Symptoms of dengue

There are also those who think some dengue patients die because of low platelets, which causes gastrointestinal bleeding.

“Those deaths were not really due to low platelets but due to dehydration that causes low blood supply to the intestines. This causes ulcer formation that results in bleeding. Plus the fact that there’s a low platelet the bleeding won’t stop. But if there was no dehydration – even if the platelet is less than 10 – the patient will still not develop intestinal bleeding. I have proven that so many times in my practice,” Dr. Mata assured.

Although there is now a vaccine for dengue, there is still no specific treatment for the disease. But Dr. Mata recommends aggressive fluid replacement. “Dextrose plus oral fluids is the key,” Dr. Mata declared. “If the patient is already admitted, he needs to continue taking oral fluids like Oresol and water to push him to urinate at one- to 3-hour intervals.”