Text by Henrylito D. Tacio

Photos from Wikipedia

Before the Philippines was rediscovered on March 16, 1521, it was a country on its own whose people enjoyed its freedom. Then, the Spaniards came, and it was never the same again.

Britannica Encyclopedia recorded the historic event: “The Portuguese navigator and explorer Ferdinand Magellan headed the first Spanish foray to the Philippines when he made landfall on Cebu in March 1521; a short time later he met an untimely death on the nearby island of Mactan. After King Philip II (for whom the islands are named) had dispatched three further expeditions that ended in disaster, he sent out Miguel Lopez de Legazpi, who established the first permanent Spanish settlement in Cebu in 1565.

“The Spanish city of Manila was founded in 1571, and by the end of the 16th century most of the coastal and lowland areas from Luzon to northern Mindanao were under Spanish control. Friars marched with soldiers and soon accomplished the nominal conversion to Roman Catholicism of all the local people under Spanish administration.”

Spanish ruled the Philippines after that. It wasn’t until 1863 that public education was available for Filipinos. Even then, less than one-fifth of those who went to school could read and write Spanish, and far fewer could speak it properly.

“The limited higher education in the colony was entirely under clerical direction, but by the 1889s many sons of the wealthy were sent to Europe to study. There, nationalism and a passion for reform blossomed in the liberal atmosphere. Out of this talented group of overseas Filipino students arose what came to be known as the Propaganda Movement,” Britannica Encyclopedia noted.

The first recorded declaration for freedom happened when Andres Bonifacio led the Cry of Pugad Lawin, which signaled the beginning of the Philippine Revolution. Members of the Katipunan tore their community tax certificates in protest of the Spanish conquest.

“The Philippine Revolution began in 1896,” Wikipedia reported. “The Pact of Biak-na-Bato, signed on December 14, 1897, established a truce between the Spanish colonial government and the Filipino revolutionaries. Under its terms, Emilio Aguinaldo and other revolutionary leaders went into exile in Hong Kong.”

Then, a war followed after that. “At the outbreak of the Spanish-American War, Commodore George Dewey sailed from Hong Kong to Manila Bay leading the US Navy Asiatic Squadron. On May 1, 1898, Dewey defeated the Spanish in the Battle of Manila Bay, which effectively put the US in control of the Spanish colonial government. Later that month, the US Navy transported Aguinaldo back to the Philippines. Aguinaldo arrived on May 19, 1898 in Cavite.”

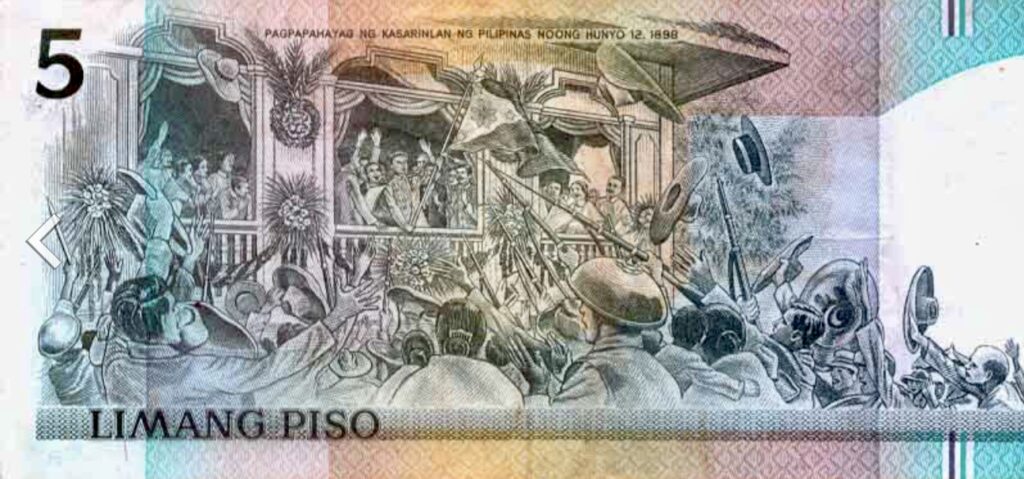

On June 5, 1898, Aguinaldo issued a decree proclaiming June 12, 1898, as the Day of Independence. The 21-page declaration said in part:

“… It was resolved unanimously that this Nation, already free and independent as of this day, must use the same flag which up to now is being used, whose design and colors are found described in the attached drawing, the white triangle signifying the distinctive emblem of the famous Society of the ‘Katipunan’ which by means of its blood compact inspired the masses to rise in revolution; the three stars, signifying the three principal Islands of this Archipelago-Luzon, Mindanao, and Panay where this revolutionary movement started;

“The sun representing the gigantic steps made by the sons of the country along the path of Progress and Civilization; the eight rays, signifying the eight provinces-Manila, Cavite, Bulacan, Pampanga, Nueva Ecija, Bataan, Laguna, and Batangas – which declared themselves in a state of war as soon as the first revolt was initiated; and the colors of Blue, Red, and White, commemorating the flag of the United States of North America, as a manifestation of our profound gratitude towards this Great Nation for its disinterested protection which it lent us and continues lending us.”

In History of the Filipino People, Teodoro A. Agoncillo wrote that the proclamation was first ratified on August 1, 1898, by 190 municipal presidents from the 16 provinces. It was again ratified on September 29, 1898, by the Malolos Congress.

The United States nor Spain, however, didn’t recognize the declaration of independence. Later on, the Spanish government ceded the Philippine archipelago to the US, leading to the 1898 Treaty of Paris. For its part, the Philippines Revolutionary government did not recognize the treaty, which led to the Philippine–American War.

Handbook Philippines: Society, Politics, Economy, Culture, considered the Philippine-America War as “marked by cruel warfare that lasted for three years.”

Authors Rainer Werning and Niklas Reese wrote in the chapter, “A History of ‘the Philippines,'”: “The 6 million-strong population of the young, short-lived republic is virtually decimated at the hands of American fighters. Rebel leader Maracio Sakay continued his resistance even after the Americans have already declared an end to the war.”

On July 4, 1946, the United States granted the Philippines the independence it had been longing for through the Treaty of Manila. July 4 was chosen as the date because it corresponds to the United States’ Independence Day. Until 1962, the Fourth of July was observed as Independence Day in the Philippines.

But on May 12, 1962, President Diosdado Macapagal issued Presidential Proclamation No. 28, which declared June 12 a special public holiday throughout the country, “… in commemoration of our people’s declaration of their inherent and inalienable right to freedom and independence.”

Two years later, on August 4, Republic Act No. 4166 was signed, renaming the July 4 holiday as “Philippine Republic Day,” proclaiming June 12 as “Philippine Independence Day,” and enjoining all Filipino citizens to observe the latter with befitting rites.

Prior to 1964, June 12 was observed as Flag Day in the Philippines. Wikipedia recorded, “In 1965, President Macapagal issued Proclamation No. 374, which moved National Flag Day to May 28 (the date the Philippine Flag was first flown in the Battle of Alapan located in Imus, Cavite in 1898). In 1994, then President Fidel V. Ramos issued Executive Order No. 179, extending the celebration period from May 28 to Philippine Independence on June 12…”

So many lives have been lost just to get the independence they long for. In Rights of Man, Thomas Paine wrote: “When it can be said by any country in the world, my poor are happy, neither ignorance nor distress is to be found among them, my jails are empty of prisoners, my streets of beggars, the aged are not in want, the taxes are not oppressive, the rational world is my friend because I am the friend of happiness. When these things can be said, then may that country boast its constitution and government. Independence is my happiness, the world is my country, and my religion is to do good.”

Independence means freedom – to do things you want to do. Freedom, according to Egypt’s Moshe Dayan, “is the oxygen of the soul.” Rabindranath Tagore shares this illustration: “I have on my table a violin string. It is free. I twist one end of it and it responds. It is free. But it is not free to do what a violin string is supposed to do – to produce music. So, I take it, fix it in my violin, and tighten it until it is taut. Only then is it free to be a violin string.”

Joseph Sizoo further explains, “Freedom is like a coin. It has the word privilege on one side and responsibility on the other. It does not have privilege on both sides. There are too many today who want everything involved in privilege but refuse to accept anything that approaches the sense of responsibility.”

Freedom is a very broad concept that has been given numerous different interpretations by different philosophies and schools of thought. The protection of interpersonal freedom can be the object of a social and political investigation, while the metaphysical foundation of inner freedom is a philosophical and psychological question. Both forms of freedom come together in each individual as the internal and external values mesh together in a dynamic compromise and power struggle; the society fighting for power in defining the values of individuals and the individual fighting for societal acceptance and respect in establishing one’s own values in it.

In philosophy, freedom often ties in with the question of free will. Libertarian philosophers have argued that all human beings are always free. Jean-Paul Sartre, for instance, famously claimed that humans are “condemned to be free.”

The philosopher Isaiah Berlin drew an important distinction between “freedom from” (negative freedom) and “freedom to” (positive freedom). For example, freedom from oppression and freedom to develop one’s potential. Both these types of freedom are, in fact, reflected in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Freedom as the absence of restraint means unwillingness to subjugate, lacking submission, or without forceful inequality. Natural laws restrict this form of freedom; for instance, no one is free to fly (though you may or may not be free to attempt to do so). “There are two freedoms – the false, where a man is free to do what he likes; the true, where he is free to do what he ought,” said Charles Kingsley, an English university professor, social reformer, historian, and novelist.