Text by Henrylito D. Tacio

Photos: Wikipedia and Washington Post

Pandemic or no pandemic, measles is here to stay. And the only way for a person, particularly children, not to be infected with it is by being immunized with the MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) vaccine.

But with the current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) rampaging around the world, including the Philippines, regular immunization is in peril. Many parents are afraid of going to health centers to have their children vaccinated in fear of being infected with the COVID-19 virus as it entails overcrowding.

“The COVID-19 pandemic caused significant disruptions to immunization services and changes in health-seeking behaviors in many parts of the world,” says the Geneva-based World Health Organization (WHO). “While the measures used to mitigate COVID-19 – masking, handwashing, distancing – also reduce the spread of the measles virus, countries and global health partners must prioritize finding and vaccinating children against measles to reduce the risk of explosive outbreaks and preventable deaths from this disease.”

Dr. Henrietta Fore, executive director of the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), thinks so, too. “Before there was a coronavirus crisis, the world was grappling with a measles crisis, and it has not gone away,” said While health systems are strained by the COVID-19 pandemic, we must not allow our fight against one deadly disease to come at the expense of our fight against another.

In the Philippines, even President Rodrigo R. Duterte has urged parents to have their children immunized during the national vaccination program. “I, therefore, call on parents under five years old as well as the local government leaders and other community stakeholders to support the immunization activity,” he said in a video message posted over the health department’s Facebook page.

First, the good news: Reported measles cases around the world have fallen compared to previous years, and progress toward measles elimination continues to decline.

Now, the bad news: The risk of outbreaks is mounting, according to a new report from the World Health Organization (WHO) and U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

“During 2020, more than 22 million infants missed their first dose of measles vaccine – 3 million more than in 2019, marking the largest increase in two decades and creating dangerous conditions for outbreaks to occur,” the report said, adding that compared with the previous year, reported measles cases decreased by more than 80% in 2020.

What is even more alarming is that measles surveillance also deteriorated, with the lowest number of specimens sent for laboratory testing in over a decade.

“Weak measles monitoring, testing and reporting for measles jeopardize countries’ ability to prevent outbreaks of this highly infectious disease,” the United Nations health agency warns.

“Large numbers of unvaccinated children, outbreaks of measles, and disease detection and diagnostics diverted to support COVID-19 responses are factors that increase the likelihood of measles-related deaths and serious complications in children,” deplored Dr. Kevin Cain, CDC’s Global Immunization Director.

A vaccinated child with her aunt

A child with measles

The WHO says major measles outbreaks occurred in 26 countries and accounted for 84 percent of all reported cases in 2020.

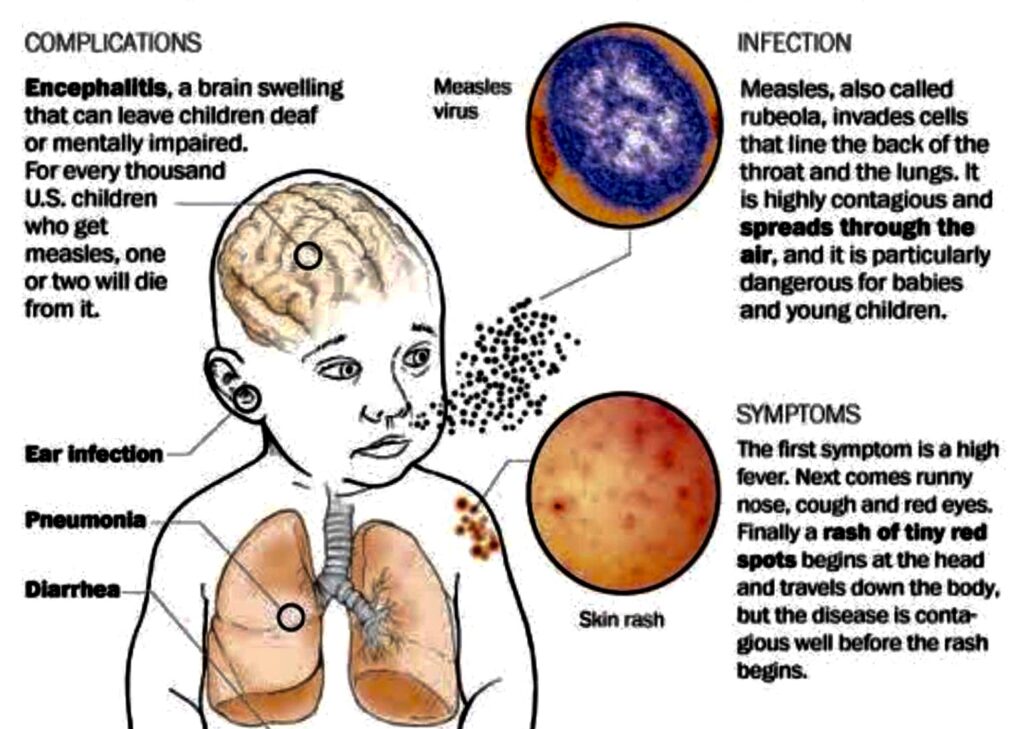

Measles – locally known as “tigdas” or “tipdas” – is a very contagious illness caused by a virus in the paramyxovirus family (which also causes mumps, German measles, and chickenpox). “The measles virus normally grows in the cells that line the back of the throat and lungs,” the WHO said. “Measles is a human disease and is not known to occur in animals.

Measles is easily spread by contact with droplets from the nose, mouth, or throat of an infected person. Sneezing and coughing can put contaminated droplets into the air. “The virus remains active and contagious in the air or on infected surfaces for up to two hours,” the WHO said.

Those who have had active measles infection or who have been vaccinated against the measles have immunity to the disease. Before widespread vaccination, measles was so common during childhood that most people became sick with the disease by age 20.

“Not vaccinating children can lead to outbreaks of measles, mumps, and rubella – all of which are potentially serious diseases of childhood,” reminded Dr. Neil K. Kaneshiro, Clinical Assistant Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Washington School of Medicine.

Health Assistant Secretary Eric Tayag said that a person infected with measles could infect up to 12-13 more people. So, how will you know that a person has measles?

“The first sign of measles is usually a high fever, which begins about 10 to 12 days after exposure to the virus, and lasts four to seven days,” the WHO informed. “A runny nose, a cough, red and watery eyes, and small white spots inside the cheeks can develop in the initial stage.

“After several days, a rash erupts, usually on the face and upper neck. Over about three days, the rash spreads, eventually reaching the hands and feet. The rash lasts for five to six days, and then fades. On average, the rash occurs 14 days after exposure to the virus (within a range of seven to 18 days).”

Most measles-related deaths are caused by complications associated with the disease. Complications are more common in children under the age of five or adults over the age of 20. The most serious complications include blindness, encephalitis (an infection that causes brain swelling), severe diarrhea and related dehydration, ear infections, or severe respiratory infections such as pneumonia.

“As high as 10% of measles cases result in death among populations with high levels of malnutrition and a lack of adequate health care,” the WHO said. “Women infected while pregnant are also at risk of severe complications and the pregnancy may end in miscarriage or preterm delivery.”

One good thing: People who recover from measles are immune for the rest of their lives.

Among those who are at risk of being infected with measles are unvaccinated young children; they are at the highest risk of measles and its complications, including death. Unvaccinated pregnant women are also at risk. Any non-immune person (who has not been vaccinated or was vaccinated but did not develop immunity) can become infected.

Until now, no specific antiviral treatment exists for the measles virus. Severe complications from measles can be avoided though supportive care that ensures good nutrition, adequate fluid intake, and treatment of dehydration with a WHO-recommended oral rehydration solution. This solution replaces fluids and other essential elements that are lost through diarrhea or vomiting. Antibiotics are prescribed to treat eye and ear infections and pneumonia.

According to the WHO, routine measles vaccination programs for children together with mass immunization campaigns are the key public health strategies to reduce global measles deaths. The measles vaccine has been in use for over 40 years. It is safe, effective, and inexpensive.

Although measles is a highly contagious disease, it can be prevented through vaccination, Dr. Tayag pointed out. He admitted, however, that the recent measles outbreak affecting the country was caused by some local government units’ failure to implement the state-sponsored immunization program in their respective areas.

“The fact that measles outbreaks are occurring at the highest levels we’ve seen in a generation is unthinkable when we have a safe, cost-effective, and proven vaccine. No child should die from a vaccine-preventable disease,” said Dr. Elizabeth Cousens, President and Chief Executive Officer of the United Nations Foundation.