Text and Photos by Henrylito D. Tacio

The name Donald “Don” Rutledge may not ring a bell to most Filipinos, but to Americans, he was one of the most noted and well-respected photojournalists. He received over 300 photographic awards from secular and religious organizations. His travels over a lifetime had taken him into 143 countries (including several times to the Philippines) and all fifty of the United States.

Don, as he wanted to be called, had done assignments for numerous publications during his long career. Some of the most well-known are Life, Time, Newsweek, US News and World Report in the United States, Paris Match in France, and Stern in Germany. His photographs also appeared in publications published in Canada, England, Brazil, and Japan, among others.

“My life has been enjoyable,” he said. “I love people and have been involved with them around the world. Friendships were formed far beyond countries, cultures, living conditions and/or styles. It helped me to realize that, beyond all these environments, people are basically the same.”

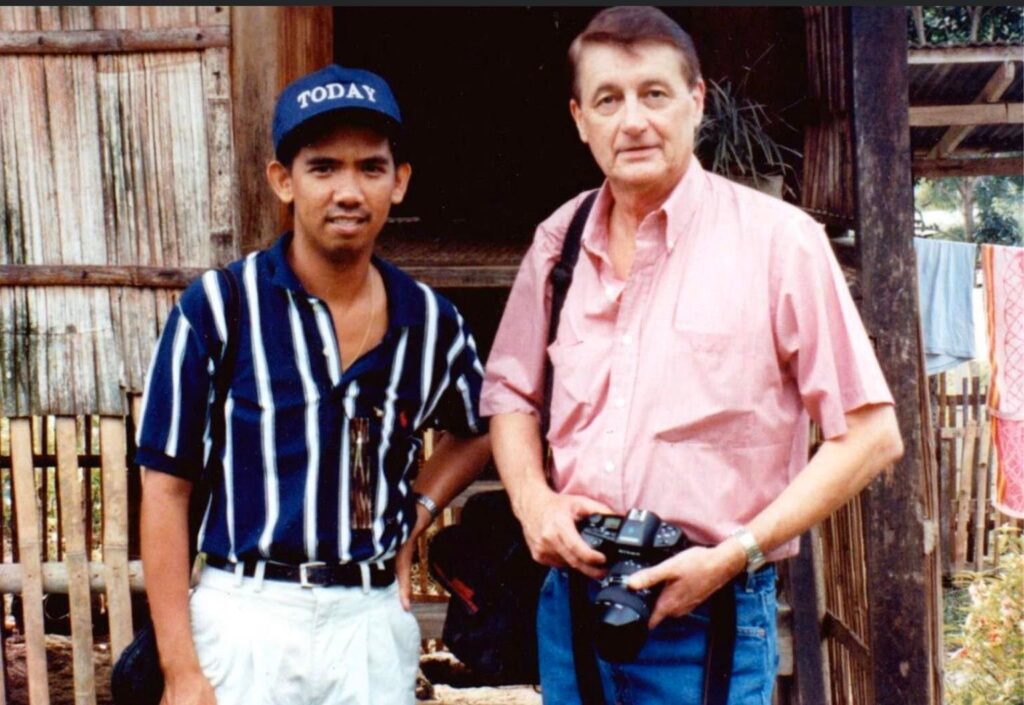

I had the opportunity of meeting Don when he came to the Philippines to cover the works of Harold R. Watson, an American agriculturist who received a Ramon Magsaysay Award for peace and international understanding. Fortunately, Watson was my boss, and being a journalist myself, I was given the task to accompany Don in his travels during his stint in our place.

During our trip together, Don shared tips about his work as a photographer. “A career in photography can be an exciting challenge whether the person chooses photojournalism, studio, wedding, portraits, advertisement, public relations, nature, or just shooting family pictures, or as a hobby,” he said.

Yes, it was from Don that I learned photography. In those times we were together, I observed that he took a lot of pictures of one particular scene or activity. On why he was doing that, he replied, “It is much like a writer or a speaker preparing an article or speech. They write lots of notes from which the message is narrowed and developed into the final presentation. I take extra pictures for that same reason.” (With digital cameras now readily available, a photographer won’t have a problem following this tip!)

“In photojournalism,” he continued, “there is constant change. A subject is smiling, frowning, talking, listening, walking, standing, sitting, working, or relaxing. Often in the background, while subjects are being photographed in the foreground, people walk in and out of the picture. Making choices as to when to click the shutter is constant and important. The challenge is both difficult and exciting. The photojournalist becomes ‘eyes’ for viewers and places those viewers into the position where he stood while making the photograph.”

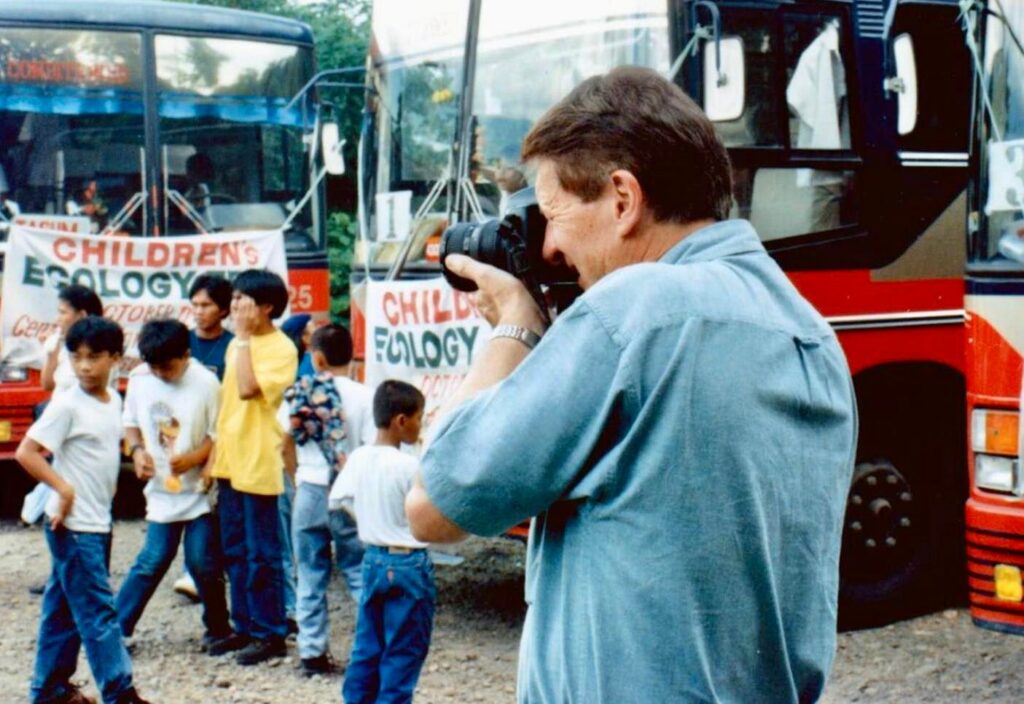

Don Rutledge at work

To those who are just starting photography as a hobby or a career, Don offered this tip: “New photographers can find excitement in isolating wonderful elements of our world and its people in that viewfinder of their camera. That becomes the photographer’s world. Outside that finder, beyond the moment of clicking the shutter, is, of course, a world of enormous size and activity, but the photographer’s world right then is defined in the viewfinder, and he freezes it to hold history as he clicks the shutter.

Don continued, “His activity should be more than just raising the camera, looking through the viewfinder and just clicking the shutter. That is a moment of personal history whether it involves special moments of his family or friends, activities of famous and unknown people, or even elements of nature scenes around him.”

More than a decade after we met, I never heard of him anymore – despite the fact that I had been to the United States several times. It was only when a former colleague posted a message on my Facebook account that Don died at his home near Richmond, Virginia, at the age of 82.

“The chance to learn from Don Rutledge was one of the best opportunities in my life,” said photographer Stanley Leary, who first encountered Rutledge as a young newspaper photographer and eventually wrote a master’s thesis about his work. “Those impacted by his work are vast. Just as vast as his stories are those he mentored. Unless Don was on the phone, his door was open at the office. While I worked with Don, I cannot remember how many people came by or called to ask for Don’s advice. No matter how bad their work, Don treated each and every one with honor, dignity and respect.”

“He believed in me as a person and as a photographer,” said Joanne Pinneo, one of Don’s protégées. Today, she has photographed stories in more than 60 countries for numerous magazines and books. She was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize, won an Alfred Eisenstadt award, and is featured in National Geographic’s “100 Best Photographs.” “Don encouraged and truly mentored me. He believed I could become a good photographer and visual storyteller.”

Don was born on a farm in Depression-era Tennessee. He originally wanted to become a pastor, but he found a creative way to communicate the gospel he originally intended to preach – through the lens of his camera. And how he discovered photography was an interesting story in itself.

“My uncle, my dad’s brother, was a soldier in the US military,” Don told me. “He was stationed in Germany where he purchased an inexpensive box camera. He never used it. Finally, I asked if I could take some pictures with it and he then gave it to me. I bought a roll of film and started taking pictures of farm animals. Then, I began taking scenic pictures of the farmland. It was then that my love for photography started.”

Don began to shoot photo stories as a freelancer and obsessively studied the work of great photographers. Some of his self-assigned stories in the 1950s and early ‘60s required considerable physical courage, including coverage of the violence surrounding the growing civil rights movement in the South. Still a raw rookie, he heard about New York-based Black Star, then America’s top photojournalism agency.

Don Rutledge and Henrylito Tacio

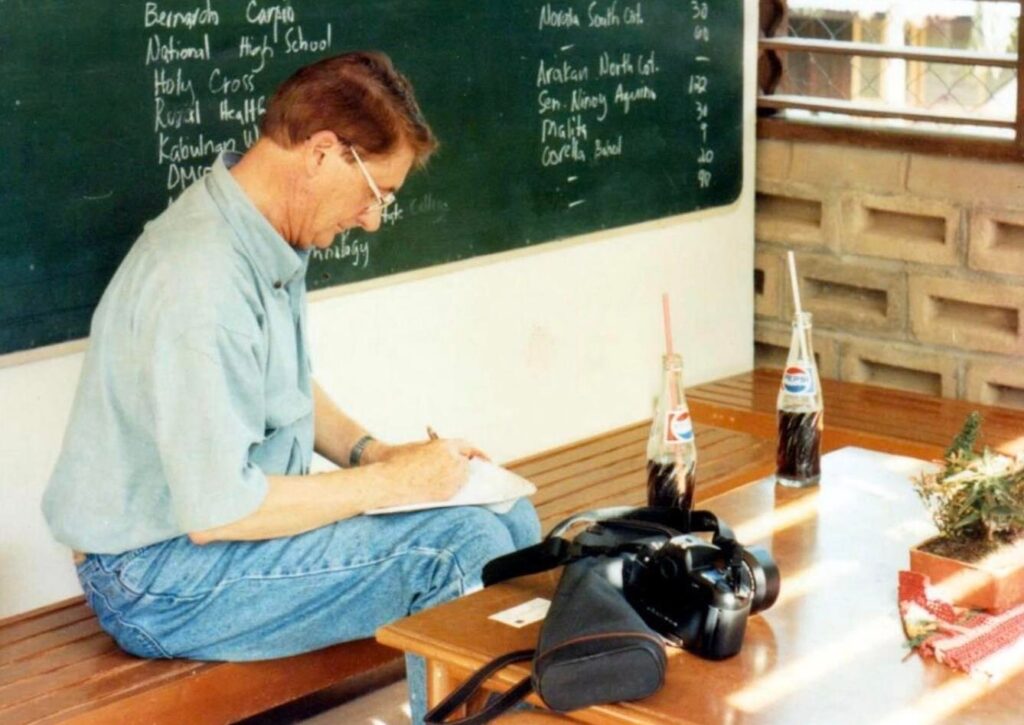

Don Rutledge taking a break

“In total ignorance, I wrote (to Black Star) and offered to do photo stories,” Don recalled many years later. “A form letter replied that they would need to see a portfolio of my work. I felt my pictures were not yet good enough for me to send a set.”

But Don sent a list of 10 story ideas. Black Star expressed a mild no-promises interest in one of them for a magazine client. Don took that response as a firm assignment, shot the story, and sent in the film. Amused and intrigued, Black Star and the magazine’s editor decided to take a chance on the young upstart and asked for more photos to fill holes in the story, which was eventually published. Don’s future was set.

But it was not until he shot the pictures for Black Like Me that Don became known worldwide. The John Howard Griffin’s 1961 book was about the author’s harsh experiences of racism in the last days of the segregation-era South when he darkened his skin to appear black.

In his racial disguise, Griffin traveled through Louisiana and Mississippi in 1959 with Don at his side. It was a dangerous assignment for the 29-year-old photographer, who never accepted the racial hatred that buffeted his Tennessee boyhood.

Black Like Me, a modern classic, sold more than 10 million copies, becoming one of the most powerful and influential chronicles of the struggle for change during the civil rights era. In 1964, a film starring James Whitmore was made based on the book.

“At the height of his potential as a globe-trotting photographer,” said an article published by the US National Press Photographers Association, “Rutledge left Black Star in 1966 to shoot pictures for the then-Home Mission Board. Several photographer colleagues told him he was crazy, but they didn’t understand his deepest motivations. He’d been searching for creative ways to communicate the Gospel since his youth in Tennessee.

“Over the next decade and more, he traveled to all 50 states, capturing the compassion of missionaries and the needs of the people they served in the pages of Home Missions magazine and three full-length books.

“In 1980, he joined the then-Foreign Mission Board as a special assignment photographer, continuing his photographic ministry worldwide for another 15 years, primarily for The Commission magazine. He formally retired in 1996, but continued doing freelance assignments in the United States and overseas until he suffered a debilitating stroke in 2001.”

On February 19, 2013, Don finally joined his Creator. “Don understood [that] the relationship of people to each other in the photo is the real power of the storytelling image,” Leary said. “Don understood that God gave His life for a relationship with each one of us.

“Nothing was more important than to establish and grow relationships. All of Don’s work was to show the power of God’s love. You either see the celebration of God’s love or you feel the sadness of someone who isn’t letting God into their life. Don helped me to realize how I could fulfill my call to ministry with the camera. Don was a pastor who realized the camera was a pulpit and the congregation wasn’t limited by the walls of a church.”