Text and Photos by Henrylito D. Tacio

Abaca, also called “Manila hemp” and known in the science world as Musa textiles, is one of the country’s endemic treasures. It’s not surprising that indigenous peoples are familiar with the premier natural fiber.

Salinta Monon, the Tagabawa-Bagobo textile weaver from barangay Upper Bitaug of Bansalan, Davao del Sur, comes to mind. She had fully demonstrated the creative and expressive aspects of the Bagobo abaca ikat-weaving called inabal.

In 1998, she was named Gawad sa Manlilikha ng Bayan by the National Commission for Culture and Arts (NCAA) for continuing what she loved doing “at a time when such craft was threatened with extinction.”

Abaca is one of the country’s 35 fiber crops. The fiber is superior over all other fibers of its class because of its great strength and its resistance to the action of water. Considered the strongest of natural fibers, it is three times stronger than cotton. In the past, it was the cordage of choice for ropes used in oil dredging or exploration, navies, and merchant shipping.

Although abaca is indigenous to the Philippines, it is now grown in Borneo, Indonesia, and Central America, particularly Costa Rica and Ecuador.

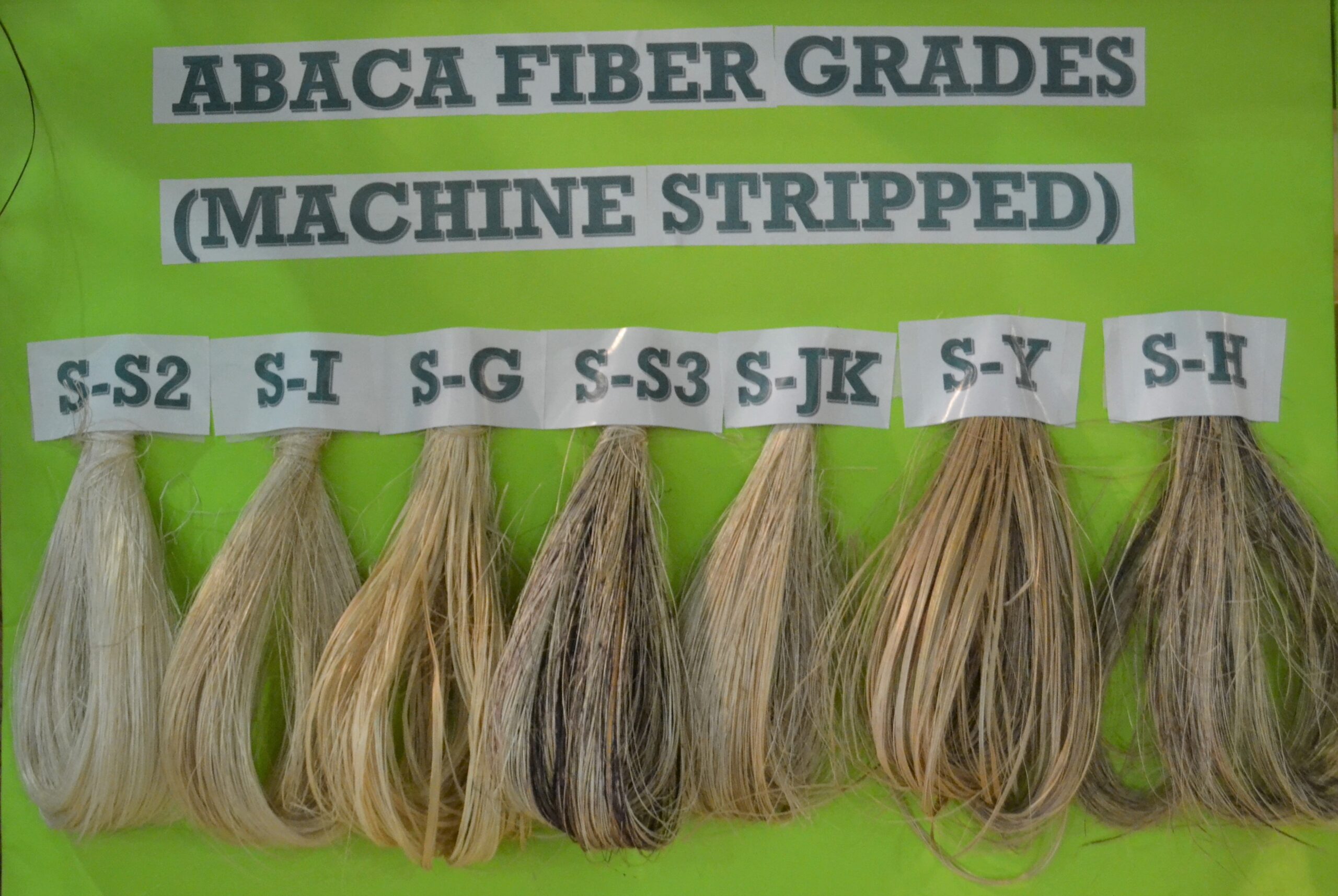

The Philippines is the number one supplier globally, as it supplies 87.5% of the world’s requirements. “An important edge that the Philippine abaca fiber has over those produced by countries like Costa Rica and Ecuador is that it has several different grades,” Philippine Fiber Industry Development Authority (PhilFIDA) reports.

The Philippines has nine grades/classifications of abaca fiber compared to only five of Ecuador, making Philippine abaca more versatile in applications. It also possesses the full spectrum of the quality of abaca that specialty paper manufacturers need.

Almost all abaca produced in the country is exported mainly to Europe, Japan, and the United States. Exports are increasingly in the form of pulp rather than raw fiber, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

“The very durable nature of abaca is not the only quality of this natural fiber that makes it in demand in the market,” said a report. “Its environment-friendly and biodegradable nature makes manufacturers, especially those in Europe, to use abaca over synthetic fibers.

“Coffee cups and tea bags are among the products that make use of abaca. These food containers highlight abaca fiber’s sanitary nature,” the report added. “Many European institutions had already adopted a policy of turning away from non-biodegradables like plastics.”

Data from PhilFIDA – a line agency of the Department of Agriculture – showed that abaca production reached 67,488.1 metric tons in 2021, higher than the 61,491.7 metric tons in the previous year.

The Davao region registered the second highest production volume at 14,618.3 metric tons. The highest production volume came from the Bicol region at 19,838.7 metric tons. Other regions with higher production volumes in 2021 include Central Visayas, Caraga, and Zamboanga Peninsula.

Aside from those mentioned earlier, abaca has many uses. For one, the fiber is used for many things, including handicraft, high-quality bags. “Our sinamay is used as blades for wind mills,” said Dr. Editha O. Lomerio, project leader of Abakayamanan, a project that combines farming of abaca with other crops like coconut. Sinamay is a natural fabric made from abaca.

Roots may be converted into fertilizer and feeds. The roots of abaca are of primary shallow root compared to hardwood trees which have deep roots. These may be uprooted more easily and may be chopped down to be made into fertilizer and feed.

Other products are electrolytic condenser paper, high-grade decorative paper, Bible paper, coffee filter, meat and sausage casings, special art paper, cable insulation paper, adhesive tape paper, lens tissue, mimeograph stencil base tissue, carbonizing tissue, currency paper, checks, cigarette paper, vacuum cleaner bag, abrasive base paper, weatherproof bristol, map, chart, diploma paper, nonwovens, and oil blotting paper.

Unknowingly, abaca also has food values. Abaca leaves, for instance, can be used as growing material for mushrooms. You may not believe this, but the flower of abaca may also be used as hamburger material.

Abaca is indigenous to the Philippines. But it was not until 1685 that abaca was known in the western world. In 1820, John White brought a few abaca fibers to the United States. By 1825, importation of abaca fiber took place.

After World War II, Furukawa Yoshizo, one of the prewar abaca plantation owners in Davao, started field-testing and successfully cultivating abaca in Ecuador. Costa Rica followed suit.

Agriculturists say the country’s agroclimatic conditions are perfect to grow abaca, which many people still mistake for the banana plant. In the Philippines, abaca has been found growing in virtually all types of soils and climate. But it is found most productive in areas where the soil is volcanic in origin, rich in organic matter, loose, friable, and well-drained, clay loam type.

Abaca matures 17 to 18 months after transplanting. It is susceptible to prolonged drought. Plant height may range from three to five meters upon maturity. It bears inedible fruits with numerous small seeds.

Abaca is easier to manage than most staple crops, although it requires regular maintenance and harvest operations. It can be grown as an intercrop with coconuts and other tall, slender trees. It can also establish itself in newly-cleared cogon grasslands and outgrow them.