Text and Photos by Henrylito D. Tacio

Additional photo: DOST

Mining is the process of extracting minerals from the earth. In mining engineering practice, it means the extraction of ores, coal, or stone from the earth. Ores are mineral deposits that can be worked at a profit under existing economic conditions. Stone includes industrial (usually non-metallic) minerals such as calcite, quartz, and other similar products.

Generally, minerals are classified into three groups, namely: metallic minerals (like iron, copper, and gold), non-metallic (example: limestone), and mineral fuels (coal is the best example).

Some of these precious minerals can be found in the Philippines, as it straddles the Western fringes of the Pacific Ring of Fire. Its grounds are very rich in economic mineral deposits, according to a speech delivered by Ramon J.P. Paje, then the secretary of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), during the Asia Mining Congress 2011 in Singapore.

The plate tectonics have caused the deposition of rich minerals in this part of the world. “The Philippines is endowed with bountiful metallic and non-metallic mineral resources,” Paje pointed out.

“Currently, gold, copper, iron, chromite and nickel are the most sought-after metallic commodities,” he said. “Among our non-metallic resources, sand and gravel, limestone, marble, clay and other quarry materials are in great demand.”

The Philippines is one of the world’s producers of metallic commodities. In 2010, the Philippines became the third biggest producer of nickel ore, behind Russia and Indonesia, vaulting over Australia and Canada.

According to Paje, the country’s mining industry “has been the subject of intense scrutiny by major sectors of Philippine society, such as local government units, civil society organizations and religious organizations.”

All these can be attributed to the “past and current experiences on the negative impacts of mining on the environment and host communities.” Because of this, “the industry continues to labor under the stigma of its ‘sins of the past.’

“This is aggravated by indiscriminate mining practices, and the lack of a unified information campaign to address misconceptions about mining,” Paje said.

There are several ways of mining – surface, underground, and open-pit, to name a few. Of these, this author is familiar with open-pit as I had been to Hibbing, Minnesota, which was built on the rich iron ore of the Mesabi Iron Range. At the edge of the city is the largest open-pit iron mine in the world – the Hull-Rust-Mahoning Open Pit Iron Mine.

“Open-pit mining is perhaps the most common mining method due to its relatively low cost.” Explains the book, Mining: Legal Notes and Materials. “Open-pit mining entails the removal of any overburden in order to expose the mineral deposit. This operation is dependent on the type of overburden. In cases where the overburden consists of highly consolidated rock, blasting (explosives) is used.”

“A valid objection is that mining operations sometimes leave the local population with little residual benefit after the mining operation,” wrote Fr. Emeterio Barcelon, SJ, in his Manila Bulletin column.

“This is not true in most cases as, for example, the Baguio area mining,” he pointed out. “If not for the mines, tourism could not have developed Baguio as it is now. But many of the local people are still poor. This is not because of mining but because of the sharing system.”

Mining operations, however expansive and complex, are temporary. Eventually, once the most accessible and valuable materials have been extracted, the mine is closed. Experts say these mined-out areas, as they are called, should be restored back to their original state.

But is this possible? Dr. Nelly Aggangan from the University of the Philippines at Los Baños (UPLB) said mined-out areas can still be rehabilitated through the government’s Greening mined-out areas in the Philippines (GMAP) program. It adopts the Bioremediation technology, which uses live microbes and plants as biological solutions to clean up and rehabilitate stressed environments such as mined-out or mine tailing areas.

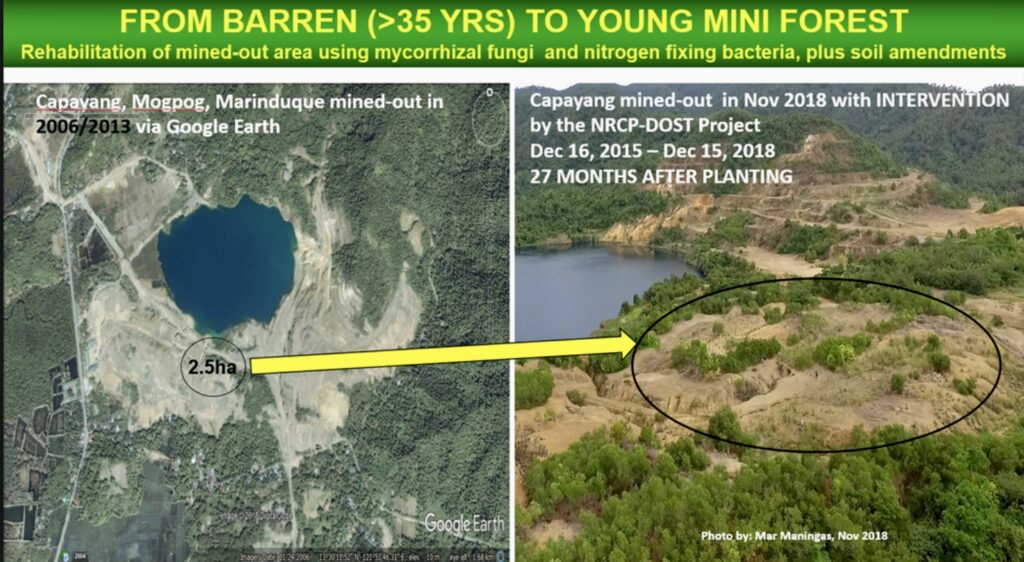

Dr. Aggangan is the leader of the GMAP program, which has successfully developed a microbial-based protocol that can effectively rehabilitate unproductive mine tailing areas in the country, converting barren lands into mini forests.

Oftentimes, mined-out areas are devoid of plants due to many biotic and abiotic factors, and one of them is the presence of residual heavy metals in the mining wastes, according to a press released disseminated by S&T Media Service of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST).

“Bioremediation is the cleaning of contaminated soil with microbes, enhancing carbon capture and reducing heavy metals contamination to surrounding communities,” Dr. Aggangan explained.

The first phase of the GMAP program was done in 2015-2018 in a copper-gold mined-out and mine tailing dumpsite in Marinduque. The protocol developed in Marinduque is now being adopted by the local government units and being replicated in Surigao, which is the second phase of the program.

The GMAP in Surigao del Norte which is expected to end this year, aims to test the effectiveness of Marinduque bioremediation protocol by assessing Marinduque isolates potency in rehabbing gold and nickel areas. It is also looking for microbes in Surigao that can help in bioremediation.

“We are expecting that these Marinduque isolates will also work in Surigao. If that is the case, we can also introduce the Marinduque isolates in all mined-out areas in the Philippines,” Dr. Aggangan explained over what could happen if the beneficial effects of the isolates from Marinduque are applied to the plants of Surigao.

The UPLB researchers developed microbial-based fertilizers MYKOVAM®, which is a soil-based mycorrhizal inoculant, and MYKORICH®, a sand-based mycorrhizal inoculant.

These developed inoculants give way to symbiosis, meaning there is a give-and-take relationship between plants and the fungus. With symbiosis, fungi derive nutrients from the soil, while plants give out carbohydrates, and this increases the population of microbes.

Dr. Aggangan clarified the difference between the traditional fertilizer and the inoculants. The former is quite expensive, easily runs out, and can even end up polluting the ecosystem, while the latter can only be applied once and lasts for a longer period.

“Pag palagi kang naglalagay ng abono, nagiging acidic yung lupa. Samantalang sa microbyo, yung acidic ginagawa nyang maging neutral para maging mas malago ang halaman. Pag acidic, posibleng mamatay or maging bansot yung halaman,” Dr. Aggangan pointed out the advantages of inoculants when applied in the soil of mined-out areas.

Inoculants cause plants to grow bigger, taller, more developed roots. Inoculated plants take out more nickel contaminants in soil. As contaminants are drawn in by plants, the soil is cleaned from toxic materials.

Despite the success of the first phase of the program, and the initial success of the second phase, Dr. Aggangan appeals to the mining companies to cooperate and allow them to conduct their research in their mining sites because their previous experience was quite a challenge.

“Hindi ko kaya ito mag-isa. Tulungan nyo po ako at lalong-lalo na sa mga andoon sa mga mining areas, please help us para naman lalong maganda ang aming maituturo sa inyo,” Dr. Aggangan pointed out.

The GMAP program is under the “Sustainable Communities,” the top priority program of the National Integrated Basic Research Agenda of the Harmonized National Research Agenda 2017 – 2022 of the DOST’s National Research Council of the Philippines.