Written by Henrylito D. Tacio

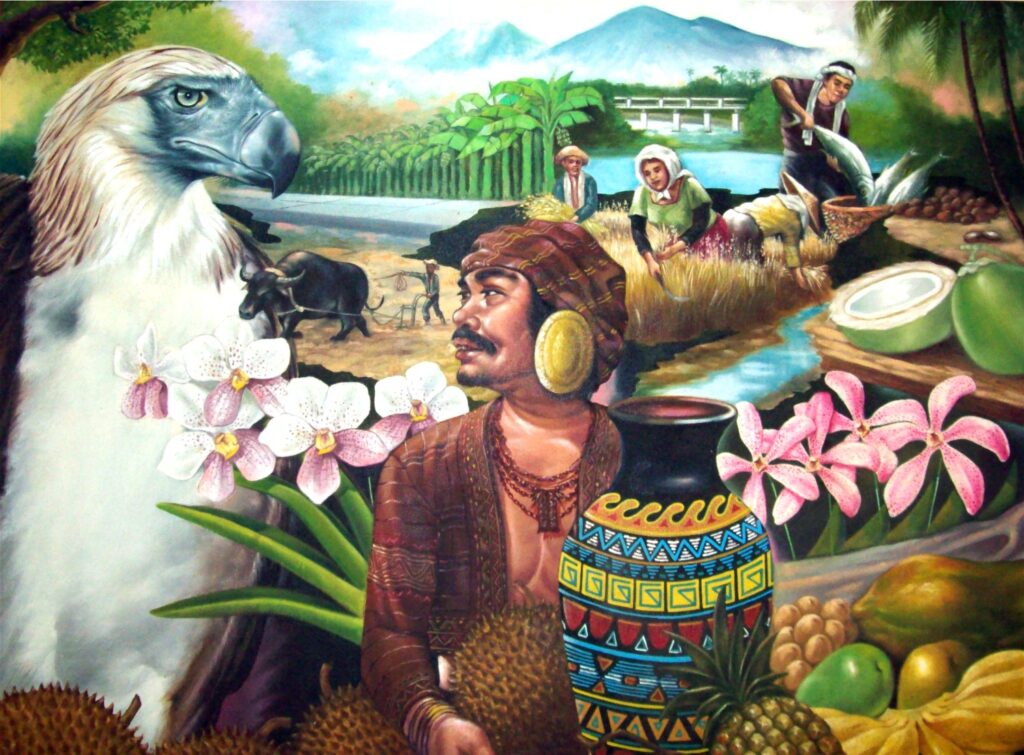

Davao City, the country’s largest city in terms of land area, is known for its ecotourism destinations. Among its top attractions is the Philippine Eagle Center, located in Malagos, Calinan, some 30 kilometers and about an hour’s ride from downtown.

The transient home of the endangered Philippine eagle (Pithecophaga jefferyii), the center is operated by the Philippine Eagle Foundation (PEF). “We are solely responsible for preserving, breeding, and caring for the bird that symbolizes the Filipino worldwide,” said Lt. Gen. William A. Hotchkiss, who used to head the foundation.

In 1995, then President Fidel V. Ramos declared the Philippine eagle as the country’s national bird. Six years earlier, the PEF came into existence.

“By using the Philippine eagle as the flagship for conservation, we are able to address a host of issues associated with the conservation and management of wildlife in the Philippine rainforest,” pointed out Dennis Salvador, the foundation’s executive director.

Since Pag-asa, the first Philippine eagle born in captivity in 1992, the foundation has bred more than two dozen eagles. Currently, the center is home not only to eagles but also other birds and other wildlife species.

“When you protect the eagle, you’re also protecting the environment,” commented Dr. James Grier, the American wildlife scientist who helped hatched Pag-asa (which means “hope” in the country’s national dialect).

“Pag-asa connotes hope for the continued survival of the Philippine eagle, hope that if people get together for the cause of the Philippine eagle, it shall not be doomed to die,” Salvador says.

“This species is considered one of the largest and most powerful eagles in the world,” Salvador continues. “Unfortunately, it is also one of the world’s rarest and certainly among its most critically endangered vertebrate species.”

The Philippine eagles are listed as critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) with an estimated number of only 400 pairs left in the wild.

It is also on the watch list of the Convention on the International Trade of Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna treaty, which regulates and prohibits the commercial import of wild animal and plant species, deemed threatened by trade.

Two major threats to the Philippine eagle’s survival are deforestation and hunting.

Forest cover is crucial to Philippine eagles. A pair needs about 4,000 to 11,000 hectares of forest land to thrive in the wild. They typically nest on large dipterocarp trees like the native lauan. In addition, they are unable to find food without the forests.

Already more than 85 to 90 percent of the original tropical forest in the country has already disappeared, according to the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR).

“The eagles no longer have a place to stay because they’re being pushed back by people,” said a PEF official. “The irony is that, man is the squatter in the eagle’s ancestral domain. Why can’t man share the forests with the eagles?”

The hunting and shooting of the Philippine eagle continues to persist, and eagles that have been turned over the PEF in recent years either had gunshot wounds or were trapped illegally in the wild.

At least one Philippine eagle is killed every year because of shooting. “Even birds that seemed healthy at the time of acquisition were found to have air gun pellets inside their bodies,” said a PEF official.

The PEF aims someday to release birds back into its natural habitat. “If time will come that we have enough stocks, where shall we release them” Salvador asked. “And how will the eagles sighted in the wild survive if factors which threaten their lives continue to haunt them?”

The eagle center has been doing its best to educate the Filipino people as to the importance of the bird and its habitat. Its facility was actually opened to the public in 1988 to raise awareness among those who visit the center. Majority of its visitors are children on school-sponsored field trips.

“Many of these children came from all over Mindanao,” Salvador said. “We use the opportunity in telling them the importance of wildlife conservation. Our mode of dissemination ranges from providing lectures, slide and film presentations, to guide tours.”

Foreigners and adults also visit the center. “Knowing what they are doing and how the birds are faring is one of the highlights of my visit to Davao,” said Melvin O. Uy Matiao, an information technology specialist from Dumaguete.

The Philippine eagle is one of the world’s largest and most powerful eagles. It is one of the two largest eagles in the world. It ranks second to the Harpy eagle of Central and South America, but only in regards to weight (averaging 8.0 kilograms vs. 9.0 kilograms) and smaller feet and legs.

An English naturalist, Dr. John Whitehead, first reported this splendid raptor in 1896 on the island of Samar. It stands a meter high, weighs anything from four to seven kilograms, and has a grip three times the strength of the strongest man on earth.

With a wingspan of nearly seven feet and a top speed of 80 kilometers per hour, it can gracefully swoop down on an unsuspecting monkey and carry it off without breaking flight.

Formerly known as monkey-eating eagle, a Presidential Decree No. changed the name to Philippine eagle 1732 in 1978 after it was learned that monkeys comprise an insignificant portion of its diet, which consists mainly of flying lemurs, squirrels, snakes, civets, hornbills, rodents, and bats.

In its website (philippineeaglefoundation.org), the PEF said they take 5-7 years to sexually mature. “It only lays a single egg every two years,” it said. “They wait for their offspring to make it on their own (usually within two years) before producing another offspring.”

The egg is incubated alternately by both eagle parents for about 58-60 days, with the male eagle doing most of the hunting during the first 40 days of the eaglet’s life while the female stays with the young.

The Philippine Eagle is found only in the Philippines. Geographically, it is restricted to the islands of Luzon, Samar, Leyte, and Mindanao. Today, most of the eagles can be found only in the surrounding areas of Mount Apo.

Efforts to save the Philippine eagle was started in 1965 by Jesus A. Alvarez, then director of the autonomous Parks and Wildlife Office, and Dioscoro S. Rabor, another founding father of Philippine conservation effort.

Rabor fought for the recognition of the plight of the Philippine eagle at the world conference of the IUCN in Bangkok, Thailand. He succeeded when the IUCN – of which the Philippines is a signatory – was declared the Philippine eagle an endangered species.

From 1969 to 1972, America’s famed aviator Charles Lindbergh spearheaded a drive to save the bird, which he called as the “noblest flier.”

Within this time frame, several helpful laws were passed. These include the Administrative Order 235 of August 25, 1970, which prohibited acts that disturbed or harmed the eagle; the Republic Act No. 6147 of November 9, 1970, and its sequel, the Wildlife General Administrative Order No. 1 (Series of 1971), which protected the eagle and provided for nest-site sanctuaries.

“By using the Philippine eagle as the flagship for conservation, we are able to address a host of issues associated with the conservation and management of wildlife in the Philippine rainforest,” Salvador said. “In addition, the eagle provides a powerful symbol for rallying support of the Filipino people.”

The Philippine eagle is truly a Filipino pride. This is the reason why the Philippine eagle has to be protected and saved from disappearance in our land.

If only Philippine eagle could speak, these would be his pleading:

“I have watched forests disappear, rivers dry up, floods ravage the soil, droughts spawn uncontrolled fires, hundreds of my forest friends vanish forever and men leave the land because it was no longer productive. I am witness to the earth becoming arid. I know all life will eventually suffer and die if this onslaught continues. I am a storyteller, and I want you to listen before it’s too late.”

Please, listen!