Text and Photos by Henrylito D. Tacio

(First of Three Parts)

The rice terraces, ingeniously carved out of the mountains by the Ifugaos for rice farming, are a living monument to the ingenuity of tribal Filipino farmers who have tilled the steep slopes for over 2,000 years.

Described as “the stairway to heaven,” it is among the top 50 Wonders of the World and has been listed on the roster of the World Heritage Sites of the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) since 1995. “A living cultural landscape of unparalleled beauty,” hailed UNESCO when it was conferred the World Heritage status.

In Kinuskusan, a barangay of Bansalan, Davao del Sur, a technology that seems to be patterned after the rice terraces is still existing. After more than four decades, it was built by an American agriculturist and Filipino counterparts.

It is called Sloping Agricultural Land Technology (SALT), and the principles being implemented in the scheme are the same as those used by the Ifugao tribes. “Instead of using rocks to build terraces, we are recommending live shrubs of various nitrogen fixing species,” explains Jethro P. Adang, the new director of the Mindanao Baptist Rural Life Center (MBRLC) Foundation Inc.

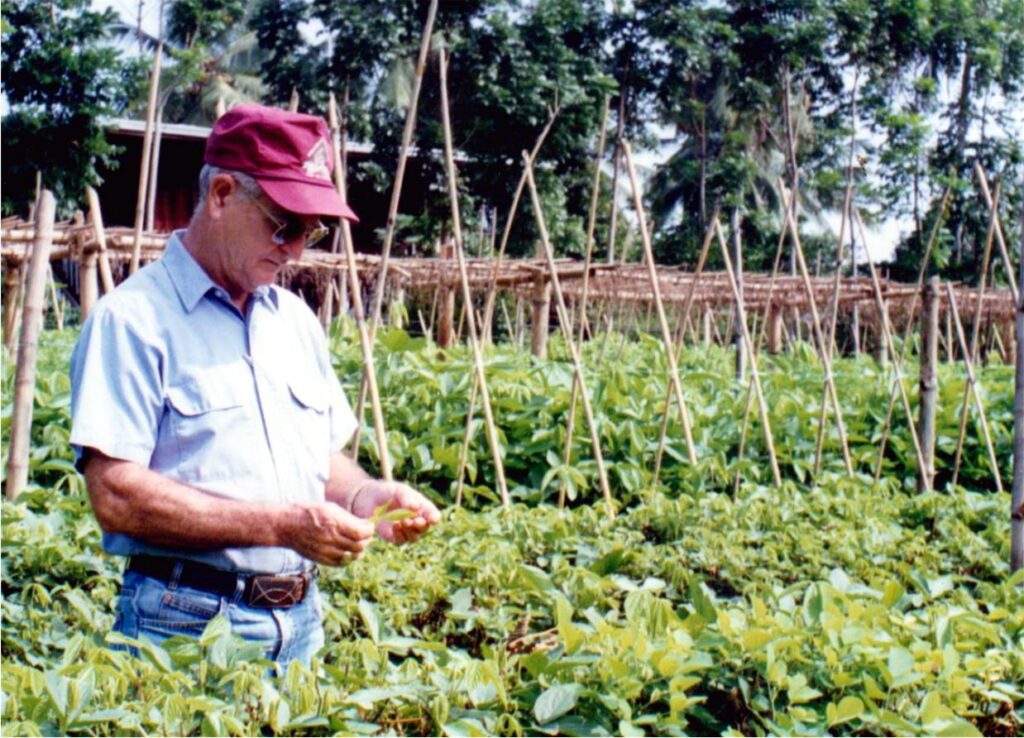

Harold R. Watson, an agriculturist from Mississippi, came to the Philippines in the 1960s. Together with the late Warlito A. Laquihon and Rodrigo R. Calixtro, they built the original SALT in the rolling mountainside of Mount Carmel in the early 1970s. “It is still existing until today,” Adang says. In fact, thousands of visitors – including those from other countries – still flock to the center to see how SALT has stood the test of time.

The MBRLC came into existence to help Filipino farmers uplift their living standard just a year before Martial Law was declared. Farmers came to the center and oftentimes complained of low and declining farm yields. They also expressed the need for better income distribution throughout the year. There were times during the year when a family had no money or food since they depended on a seasonal monocropping system.

Recognizing these problems, the MBRLC tried to find some ways. Watson and his staff kept experimenting, searching for something simple and practical that could help stem the tide of topsoil washing down the mountainsides. They believed soil erosion was the primary culprit of low production.

If President Rodrigo R. Duterte is hell-bent on curbing, if not stopping, the proliferation of illegal drugs, which has destroyed so many lives already, the government should also engage itself in the war against soil erosion. It’s an enemy that most Filipinos are aware of, but no one seems to recognize it. It attacks in broad daylight and creeps at night when everyone is sleeping.

And because the soil is less spectacular, the media focused more their attention on other environmental issues and concerns like energy crisis, fuel problems, climate change, ocean acidification, biodiversity, logging, and forest fires.

“Soil erosion is an enemy to any nation — far worse than any external enemy coming into a country and conquering it because erosion is an enemy you cannot see vividly,” said Watson when he accepted the Ramon Magsaysay Award in 1985 for developing SALT and other MBRLC technologies. “It’s a slow creeping enemy that soon possesses the land.”

While experts talk about biotechnology, organic farming, high-value crops, more crop production, and exportation, they fail to include soil – “the bridge between the inanimate and the living” – in the equation. After all, it has been estimated that more than 99 percent of the world’s food comes from the soil.

Estimates from the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) showed about 10,000 cubic meters of arable soil per hectare are eroded annually, such an amount equivalent to a one-meter layer of soil thickness removed per hectare per year.

According to Watson, soil erosion will imperil the country’s food supply in the coming years. “Soil is made by God and put here for man to use, not for one generation but forever,” he reminded. “It takes thousands of years to build one inch of topsoil but only one good strong rain to remove one inch from unprotected soil on the slopes of mountains.”

But there was an interesting story on how SALT came to be. One day, Watson and some of his staff gathered together in one room to brainstorm. “We decided to start with what we knew,” Watson recalled. “We could run a contour or a terrace line, but how could we keep it there? Suppose we took this ‘miracle plant’ people had been talking about growing in the flatlands and put it around the terrace in hedgerows.”

The “miracle plant” he referred to was “ipil-ipil,” known in the science world as Leucaena leucocephala. (When it was devastated by psyllid infestation in later years, the MBRLC recommended other nitrogen-fixing species like Desmodium rensonii, Flemingia macrophylla, and Gliricidia sepium.)

“It’s a legume, we would be enriching the soil,” Watson further said. “Then, we’d take the green leaves of this plant and put them back on the soil. We knew that one line wouldn’t hold the soil, so we said, ‘Let’s make a double line.'”

They got excited. If the method worked, it would stop erosion, rebuild soil and increase crop yield. Within an afternoon, the basic theory of Sloping Agricultural Land Technology (SALT) was born.

“SALT is one of the solutions to the problems that beset the world these days,” said Adang. “But it seems that most experts are looking for big things that can help curb, if not arrest, the difficulties this planet has gotten into.”

Just like the prophet David defeated giant Goliath with just a slingshot and a stone, the problems can be solved by going back to the basics, Aldang said. “We don’t need modern technologies and high gadgets to defeat the enemy. All we have to do is use what God has provided us through the years.”

SALT is one possible answer that should be given much attention. “Basically, the SALT method involves planting field and permanent crops in 4-5 meter bands between double-controlled rows of nitrogen fixing trees and shrubs,” explains Adang.

Examples of field crops are legumes (beans, peas, and pulses), cereals (upland rice, corn, and sorghum), root crops (sweet potato, cassava, carrot, and taro), and vegetables (cabbage, ampalaya, tomato, eggplant, etc.). Permanent crops include cacao, coffee, banana, citrus, and fruit trees.

This is where food security comes in. “Most farmers are locked into one crop,” Adang points out. “When the crop is harvested, he has much money, but it is soon gone, and he has overspent. He’s called a millionaire for one day.”

With SALT, a farmer can harvest every now and then. “He has something to look for,” Adang says. “Because the harvested crops are just enough for the market, there is a tendency that the price of his produce is much higher.”

Organic farming is practiced in the SALT scheme. Double hedgerows of leguminous perennials are planted at 4-5 meter intervals on equal-elevation contours. The hedgerows are pruned frequently (every 5-6 weeks), and the cuttings are applied to the crops as a source of fertilizer. The cuttings also served as mulching materials.

In the SALT farm, you find a mix of permanent crops, cereals, and vegetables. Every third strip of available land is normally devoted to permanent crops. A combination of various cereals and vegetables are planted on the remaining two strips of land. Each has its own specific area so that there can be a seasonal rotation.

“Crop rotation helps to preserve the regenerative properties of the soil and avoid the problems of infertility typical of traditional agricultural practices,” explains Adang on the importance of regular rotation of crops.

SALT can help control soil erosion. A seven-year study conducted at the MBRLC showed that a farm tilled in the traditional manner erodes at the rate of 1,163.4 metric tons per hectare per year. In comparison, a SALT farm erodes at the rate of only 20.2 metric tons per hectare per year.

The rate of soil loss in a SALT farm is 3.4 metric tons per hectare per year, which is within the tolerable range. Most soil scientists place acceptable soil loss limits for tropical countries like the Philippines within the range of 10-12 metric tons per hectare per year. The non-SALT farm has an annual soil loss rate of 194.3 metric tons per hectare.

As SALT is an example of agroforestry (a collective name for all land-use systems and practices where woody perennials and crops are planted together), it offers other valuable ecological advantages.

“SALT greatly reduces the risk of drought, landslides, floods, the silting over of low-lying areas, and wind erosion — all of which are linked to the radical transformation of the natural environment and the destruction of the mountain forests,” Adang says.

SALT was heavily promoted in the 1990s up to the late 2000s by various government agencies (particularly agriculture, agrarian reform, science, and technology) and non-government organizations.

But despite the sustainability of the SALT system, some Filipino farmers still abandon their SALT farms after several years. According to Adang, it’s not an easy task to follow the SALT system diligently. “We have had our failures, too,” he admits. “I can take you to a lot of farms that started out with SALT, and about halfway through the farmers just gave up. Part of it could be our fault; maybe we didn’t motivate them enough.”

SALT may be sustainable, but Adang believes it is not a perfect farming system.

“SALT is not a miracle system or a panacea,” Watson once pointed out. “To establish a one-hectare SALT requires much hard work and discipline. It took many years to deplete the soil of nutrients and lose the topsoil; no system can bring depleted, eroded soil back into production in a few short years. The price of soil loss is poverty, but we have seen land restored to a reasonable level of productivity by using SALT.” (To be continued)