Text by Henrylito D. Tacio

Photos: Wikipedia

The Island Garden City of Samal is known for its fine white-sand beaches. But there’s one place visitors should not miss going to is the Giant Clam Sanctuary in the peaceful barangay of Adecor in the Kaputian district. It is a must if you love snorkeling.

The sanctuary is part of the Taklobo tours, which the tourism office of the local government is promoting. The entrance fee is only P100 but to get there, you have to rent a boat, which charges a minimal fee for a group.

“It will be a once in a lifetime experience,” our boatman said. “You get a glimpse up close of giant clams in different sizes and colors.”

Almost 3,000 giant clams of four species are spreading all over the 14-hectare sea. The most notable of these species is the biggest among the giant clams, the Tridacna gigas. Other species found in the area are T. deresa (smooth giant clam), T. squamosa (fluted giant clam), and T. hippopus (strawberry clam or bear claw clam).

The sanctuary came into existence when the Davao del Norte State College (DNSC) was given the privilege to manage the Marine Reserve Park and Multi-purpose Hatchery.

Having entered into a partnership with the University of Philippines-Marine Science Institute for the giant clam stock enhance the program in 2001, DNSC saw the beginning of various local and national collaborations.

In response to the call for conservation and increasing interest among locals and international tourists on giant clams, DNSC implemented the community-based Taklobo Tours in tandem with the city government, barangay local officials, and Adecor United Fisherfolk Organization.

All stakeholders agreed, and the project started to roll on in February 2013 with the aim of promoting biodiversity conservation, enhancing eco-tourism, building capacity, and providing livelihood. Its immediate beneficiaries are the fisherfolk, who serve as local tour guides and conservation advocates.

“We raise awareness by informing the people who come how endangered these giant clams are and that there are now laws regarding its preservation,” Joel Gonzaga, one of the members of the organization, told us during our visit. “It is now prohibited to harvest them and there are some consequences if they do so – with fines up to three million.”

The Taklobo Tours offers tourists a one-of-a-kind underwater adventure they will never forget. To experience this, you must take the two-hour (including travel time) from Santa Ana Wharf in Davao City, or just a 5- to 7-minute boat ride from barangay Adecor to the Marine Reserve Park.

I wasn’t able to dive into the waters to see the giant clams. But here’s a comment of one tourist who did: “Awesome and inspiring marine sanctuary that protects several species of giant clams. With our snorkel masks on, we were led underwater by a certified guide to witness firsthand these amazing sea creatures. We also learned about their habitat, life cycle and feeding. A definite must-see.”

Giant clams come in different sizes and colors, including yellow, blue, brown, green, and violent. Under the sea, they look like colorful flowers. No one knows how old they are, but most of them are beyond ten years. (They can live up to 100 years). In the sanctuary, giant clams may grow up to one meter long.

Giant clams

Giant clam

Giant clam

Giant clams are solar animals that need the sun to grow, survive and thrive. Most of them prefer to live in shallow waters, particularly in the coral reef areas (kagasangan) that makes them vulnerable to poaching and exploitation.

Giant clams may have existed even during the time when dinosaurs roamed around this planet. “They have been around for over 38 million years,” wrote Vicky Viray-Mendoza, the executive editor of Maritime Review Magazine. “Antonio Pigafetta, the Italian navigator who joined Ferdinand Magellan in his sea travels around the world, documented these giant clam species as early as 1521 in his journal.”

Some people feared them because there are some talks that they would attack people once they swim in areas where the clams are living. But that’s a myth, according to National Geographic. It happened in the movies, but there are no authentic cases of people being trapped and drowned by giant clams.

A reef assessment conducted in the country in the 1970s showed that giant clams were close to becoming locally extinct for several reasons, but particularly due to poaching, overharvesting, and habitat destruction.

In addition, giant clams are highly vulnerable in the wild to stock depletion because of their late sexual maturity and immobile adult phase. As giant clams cannot literally move due to their heavyweight (as much as 250 kilograms), they reproduce via external fertilization, where eggs and sperm are released into the water column at the same time.

To save the giant clams from extinction, the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species (CITES) and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) included them in the list of endangered species. Towards the promotion of this advocacy, the government passed Republic Act No. 8550, otherwise known as the Philippine Fisheries Code.

A person committing the unlawful act will be imprisoned for five to eight years and a fine equivalent to twice the administrative fine and forfeiture of species.

In 1985, marine biologist Edgardo Gomez launched a program to replenish locally extinct giant clam populations across the country. That effort has continued despite Gomez’s death in 2019.

Despite the laws and programs initiated by communities, private entities, and school institutions to save giant clams, there are still others who try to make money out of these endangered species.

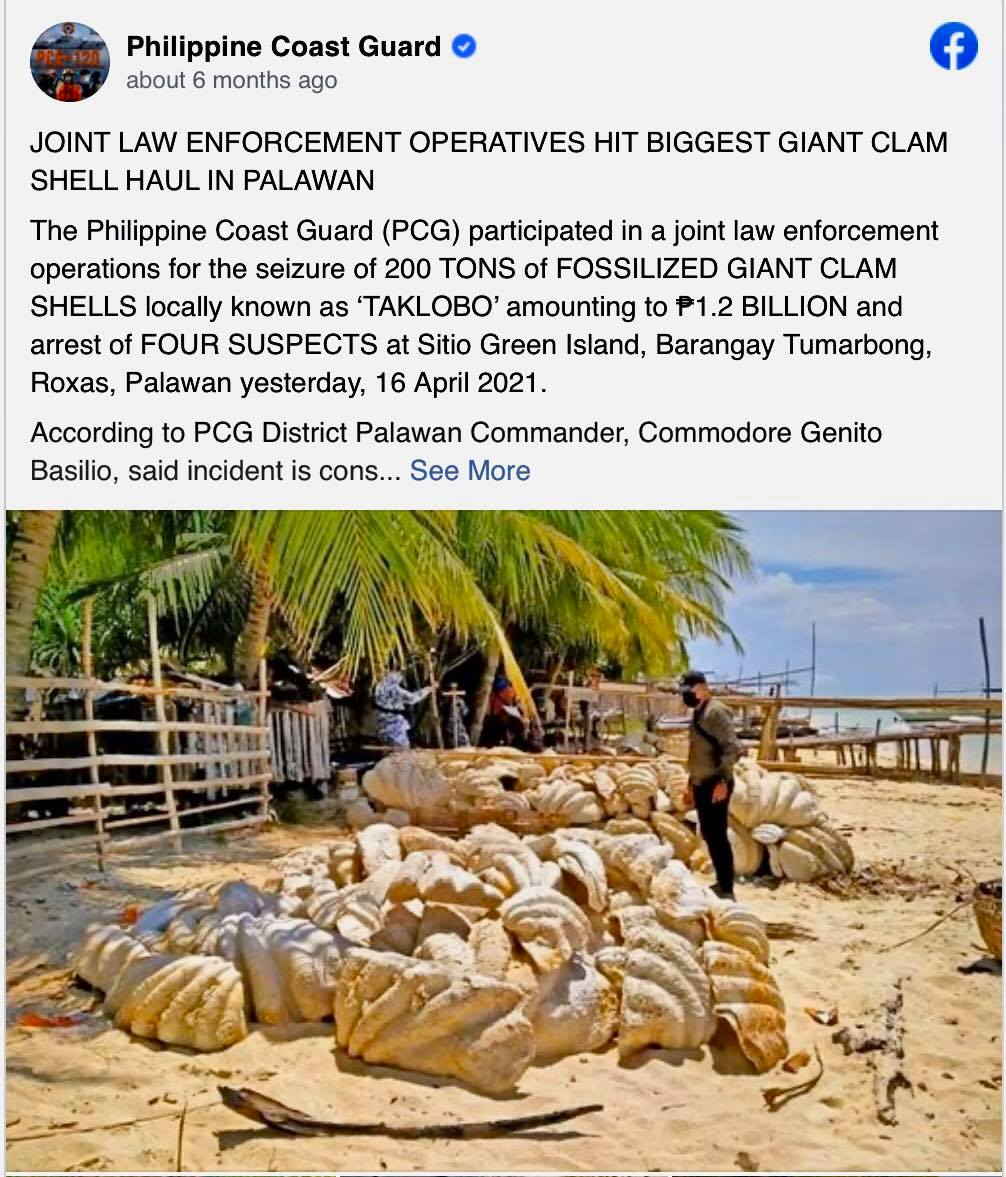

Early this year, more than 200 tons of fossilized giant clam shells, worth 1.2 billion, were seized in a joint law enforcement raid in Palawan.

Aside from being called “white gold of the sea,” giant clams are also known as “king of all shells.”