Text by Henrylito D. Tacio

Photo: Wikipedia

We never knew it was coming. Before my grandfather, Magno Tacio, died at the age of 72, he never showed any unusual behaviors. But four months after my grandmother, Modesta Tacio, turned 66, she started acting strange. She kept on forgetting simple things like where she placed her keys and if she had eaten her lunch already.

“Don’t worry,” my aunt Lydia told her. “Forgetfulness happens once in a while.”

But as months progressed, her forgetfulness was getting worse. She could no longer remember the names of her grandchildren. “What’s your name again?” she would often inquire.

During the 1998 Christmas, we came to her house before midnight as a family tradition. We sang Christmas carols, and five minutes before midnight struck, we went to the table for our Noche Buena. I was completely surprised when my grandmother asked me, “Who are you?”

My grandmother belongs to what demographers called an “aging population” or those aged 60 and above. In Asia, their number is growing as a result of higher standards of living, better nutrition, and improved health care. By 2050, the figure is expected to hit 1.2 billion – a quarter of the region’s population, according to the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific.

No matter how healthy or autonomous older people appear to be these days, the fact remains that age brings with it the heightened risk of a variety of degenerative diseases and psychological concerns.

Among the health problems the elderly usually encounter include cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, osteoporosis, difficulties of hearing and vision, not to mention Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease (which Tina was diagnosed with).

While many of these diseases and health problems are becoming treatable, they show few signs of being curable. Instead, they are becoming the chronic diseases of modern society, often difficult to manage socially and even more costly to manage medically.

More importantly, the psychosocial needs of the elderly also become more pronounced with age. “The need for companionship, the need to feel wanted, and the need for social and emotional support are central themes in everyday lives of older people,” someone pointed out.

As such, taking care of the elderly is the country’s future challenge. But how?

Seek advice from the experts

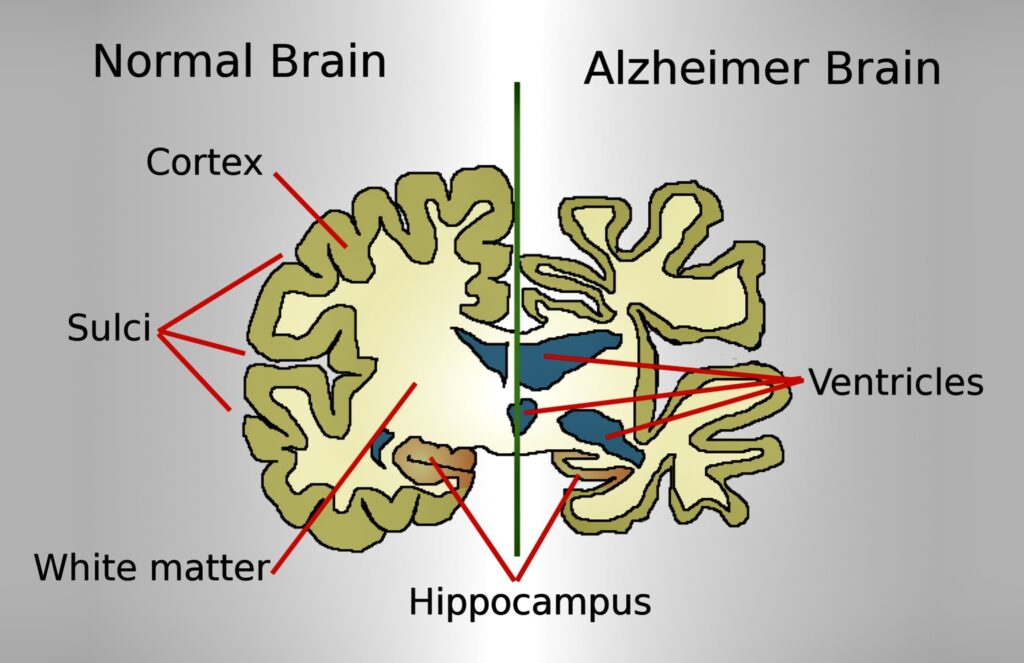

We thought the strange behaviors my grandmother exhibited were part of being old. But we were wrong. After a series of tests, our doctor told us that she was suffering from Alzheimer’s disease, a progressive degenerative brain syndrome that affects memory, thinking, behavior and emotion.

Alzheimer’s disease is more common among the elderly. “Alzheimer’s occurs very rarely among those 40-50 years old, increases between 60 and 65, and is very common over 80,” says Dr. Simeon Maragisan, a professor at the Department of Neurology and Psychiatry at the University of Santo Tomas.

“About 5% of men and 6% of women over 60 years of age are affected with Alzheimer’s,” informs Dr. Wang Xiangdong, who was the adviser of the mental health and control substance abuse program of the regional office of the World Health Organization at the time when interviewed by this author.

Learn as much as possible about the disease

Find out as much as possible about the disease. Information about what the disease is, the signs and symptoms, and what to do can be obtained by interviewing doctors and other health professionals, social workers, and from reading books and magazines. You can even google some information from the internet.

Be sure to substantiate all the information you have gathered. A little learning so goes a familiar saying, is a dangerous thing. So, don’t rely on what you read, heard or seen. For instance, if there is a drug recommended, consult with your doctor before giving it to the patient.

Another source of information: self-help groups or support organizations. “Looking after an Alzheimer’s disease patient requires a lot of skills like how to prevent the patient from getting glost and how to help the patient to remember certain essential things, among others. One can learn all these from other families who have the same problem,” says Dr. Victor Chong, a neurologist with a special interest in dementia from the University of Malaya Medical Center in Kuala Lumpur.

Delegate who takes care of the patient regularly

Old age is often seen as “an illness” with no cure. Among Filipinos, the basic responsibility for the management of a person with a disease rests with the family. And for someone having Alzheimer’s, the family is the microcosm of the whole world.

After my grandmother was diagnosed, my father, Generoso, who is the eldest, convened the five siblings for a family reunion. After a hearty dinner, they deliberately discussed my grandmother’s status: who will take care of her?

Being unmarried at that time, my aunt Lydia was given the task. At the start, it was alright. But as the disease progressed – when my grandmother was almost child-like, being completely dependent on her in terms of being fed, bathed, and dressed – aunt Lydia grumbled. She never had any social life anymore. “I’m fed up,” she said.

Alzheimer’s disease is a long-term illness that requires a lot of care and love from family members. And attending someone with this disease is stressful and demanding, according to Dr. Miguel Ramos, Jr., former head of the geriatric center of St. Luke’s Medical Center.

“People with Alzheimer’s have difficulty in recognizing relatives, friends and even themselves when facing a mirror,” Dr. Ramos explained. “They have difficulty understanding and interpreting events, have difficulty walking and finding their way around the house. They also would have bladder and bowel incontinence and therefore personal hygiene is a challenge for anyone taking care of an Alzheimer’s patient. They also have inappropriate behavior in public or just plain combative and aggressive to the caregiver or loved ones. Or, they may be passive and confine themselves to a wheelchair or bed.”

Don’t leave the patient unattended

Alzheimer’s has a gradual onset. Usually, it starts with subtle changes in memory function. “Memory loss may be the most apparent – and earliest – problem in Alzheimer’s disease but other symptoms are equally annoying to the patient and alarming to the relatives,” explains Dr. Marasigan.

That was what happened to my grandmother. At one time, she went alone – without my aunt Lydia’s knowledge – to the public market, about a kilometer away from home. She used to do this before the disease sets in. On her way back, she became disoriented and was completely lost.

We went frantic when my aunt Lydia told me that my grandmother never came home that day. We searched for her all over the town but failed to find her. “Have you seen this woman” we inquired. But most people we asked replied negatively.

Two days later, someone came to us and reported that he saw an old woman in New Clarin, a barangay some eight kilometers away from the town. My father immediately went to the place, and sure enough, it was my grandmother. He found her sleeping under a mango tree. “I could no longer remember the road going back home,” she said, crying while embracing my father.

Give the caregiver a break

Actually, Alzheimer’s disease has two victims: the patient and the caregiver. In most cases, Alzheimer’s is more agonizing for the caregiver than for the patient. It is not only physically demanding but also emotionally draining. In most instances, a caregiver experiences stress which usually manifests through denial, anger, social withdrawal, anxiety, depression, exhaustion, sleeplessness, irritability, and lack of concentration.

Studies done in the United States found that caregivers of Alzheimer’s patients – compared to other people their age – have 70% more physician visits, are 50% more likely to suffer depression, and use 40% more medications.

Caregivers should be given a break by taking over caregiving responsibilities for a few days by other members of the family. “We sometimes advise the caregivers to bring those with Alzheimer’s to a day care center where trained nurses could take care of them,” suggests Prof. Kua Ee Heok, a consultant psychiatrist from the National University of Singapore.

Accept it

Death, like taxes, is inevitable. Sometimes, you can postpone it, lessen its physical pains, deny its existence, but you cannot escape from it. There is no single cause of death associated with Alzheimer’s. Many sufferers die from problems related to the decrease in brain function.

“When Alzheimer’s is the cause of death, patients often die because of the complications related to the disease like pneumonia, urinary tract infection, and skin infection from pressure sores,” says Dr. Chong.