Text by Henrylito D. Tacio

Photos: Wikipedia and medicinenet.com

These days, nobody talks about tuberculosis (TB). But in the distant past, it was one of the most dreaded diseases – just like the current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). One of the famous victims was President Manuel L. Quezon, who died of the disease in the United States in 1944.

In 1938, the Quezon Institute, a sanatorium for TB under the Philippine Tuberculosis Society, was inaugurated with the President himself gracing the occasion.

“Six years ago, when I was in the United States on an important mission on behalf of the Philippines, I started to feel chest oppression and back pain, and became easily fatigued,” Quezon said in his speech. “As my work needed all my strength and I could ill afford to be sick at the time, I took the first opportunity to consult a famous lung specialist in New York City. After subjecting me to a rigorous physical and fluoroscopic examination, the doctor diagnosed my case as tuberculosis of the lungs.”

Many Filipinos thought TB was already vanquished as it is a disease of antiquity. Unfortunately, it is very much around.

“With the development of new TB drugs and improved living conditions, TB disappeared from the lives and minds of many… But today, we are faced with a global epidemic that is killing more people than at any point in its history,” said then Director-General Gro Harlem Brundtland of World Health Organization (WHO) in a TB conference convened in Amsterdam in 2000.

Public health monster

Twenty years later, in 2020, Dr. Rafael Castillo, a widely-read columnist of Philippine Daily Inquirer, called TB as “the biggest public health monster” in the country.

The reason: “Approximately, 74 Filipinos die of TB every day and is among the top 10 causes of death in the country,” says the Department of Health (DOH) on its website.

About one million Filipinos have active TB disease, according to the United Nations health agency. “This is the third highest prevalence rate in the world, after South Africa and Lesotho,” said Dr. Gundo Aurel Weiler, director of the WHO Western Pacific.

This is very alarming. “Each person with active TB can spread the disease to 10 other people,” warns Dr. Lawrence Domingo in a feature he wrote for pharexmedics.com. “Once active TB is treated, the person is no longer contagious after 3 weeks.”

According to Dr. Domingo, about 80% of Filipinos have latent TB. “This means that Filipinos have a TB infection, but are still in the inactive stage,” he explained. “That is why they have no symptoms and are not contagious to other people.”

The WHO envisions ending TB from the world by 2030. “Yet, the Philippines is among the few countries where the number of people with TB continues to increase every year,” Dr. Weiler lamented.

COVID-19 pandemic

The current pandemic is fueling the disease. Today, many TB-affected individuals in the country dismiss getting checked due to the fear of contracting COVID-19. There is also a lack of education towards treatment. In addition, many Filipinos perceive TB as a low-risk disease.

Last year, the health department recorded a decline in TB cases. “We see this as a direct effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on a critical disease prevention and control program like TB,” said Health Secretary Francisco T. Duque III. “The quarantine has extremely affected and limited the health seeking behaviors of our fellow Filipinos.”

Dr. Duque said that, unlike other health programs, having fewer cases is not an indicator of success for the country’s TB program. “Our goal for our TB program is to find and treat as many TB cases as possible,” he said. “Only by finding and treating these cases can we limit its spread and achieve our dream of a TB-free Philippines.”

But he cautioned. “Over 100,000 Filipinos may die of TB in the next five years or 20,000 TB deaths per year if TB services continue to be disrupted because of mobility restrictions brought about by COVID-19,” the health official said.

Among those who are more prone to becoming ill with TB are people with weakened systems, including those living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), diabetes, malnutrition, and smokers.

The top three groups most vulnerable to TB, according to the health department, are males and smokers, the elderly, and those who were previously treated.

Ancient disease

The tenacious TB bacillus has preyed on people since antiquity. TB-induced skeletal deformities point to the disease’s existence as early as 8000 BC. Unmistakable signs of tubercular bone decay were found in the skeletons of Egyptian mummies as long ago as 2400 BC.

In 1882, German pathologist Dr. Robert Koch finally unearthed the mystery of TB’s origin when he discovered the TB bacillus, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, on March 24. Koch’s colleague, Dr. Paul Ehrlich, recalled, “Koch appeared before the public with an announcement which marked a turning point in the story of a virulent human infectious disease. In clear, simple words, Koch explained the aetiology of tuberculosis with convincing force, presenting many of his microscope slides and other pieces of evidence.” He was awarded the Nobel Prize of Medicine in 1905 for his discovery.

Despite the discovery, TB continued to take its toll. “Year after year, century after century, TB tightened its relentless grip, worsening with wars and famines that reduced people’s resistance, infecting virtually everyone but inexplicably sparing some while destroying others,” wrote Dr. Frank Ryan, author of Tuberculosis: The Greatest Story Never Told.

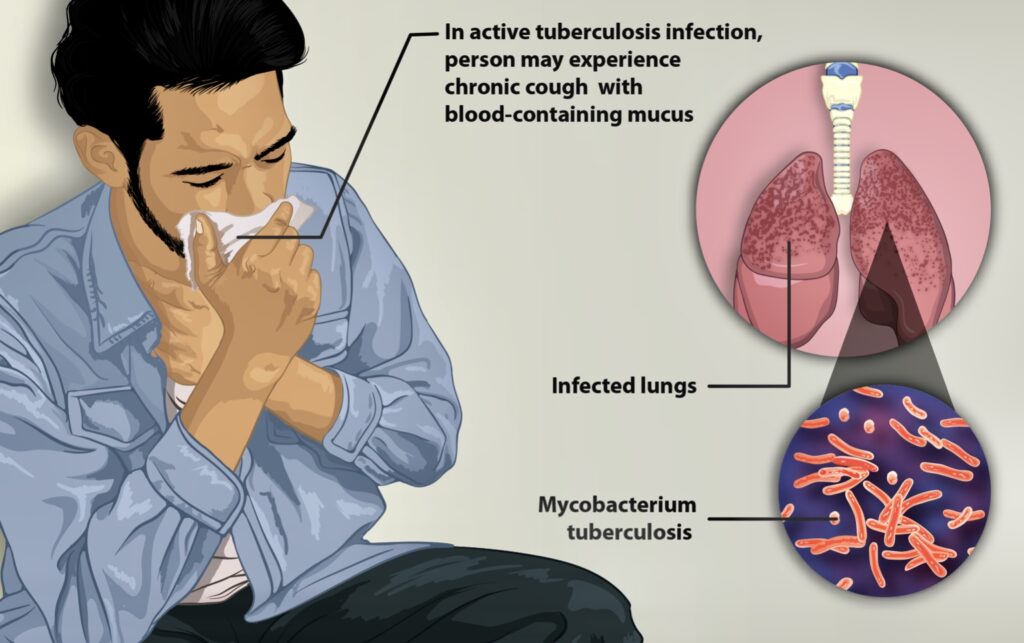

Like the COVID-19 virus, TB is spread from person to person through the air. “When people with lung TB cough, sneeze or spit, they propel the TB germs into the air,” the WHO explains. “A person needs to inhale only a few of these germs to become infected.”

A less common route of transmission is through the skin. Pathologists and laboratory technicians who handle TB specimens may contract the disease through skin wounds. TB has also been reported in people who have received tattoos and people who have been circumcised. A person may become infected with TB bacteria and not develop the disease. His or her immune system may destroy the bacteria completely.

“People infected with TB bacteria have a 5-15% lifetime risk of falling ill with TB,” the WHO says. “Those with compromised immune systems, such as people living with HIV, malnutrition or diabetes, or people who use tobacco, have a higher risk of falling ill.”

Familiar signs of TB

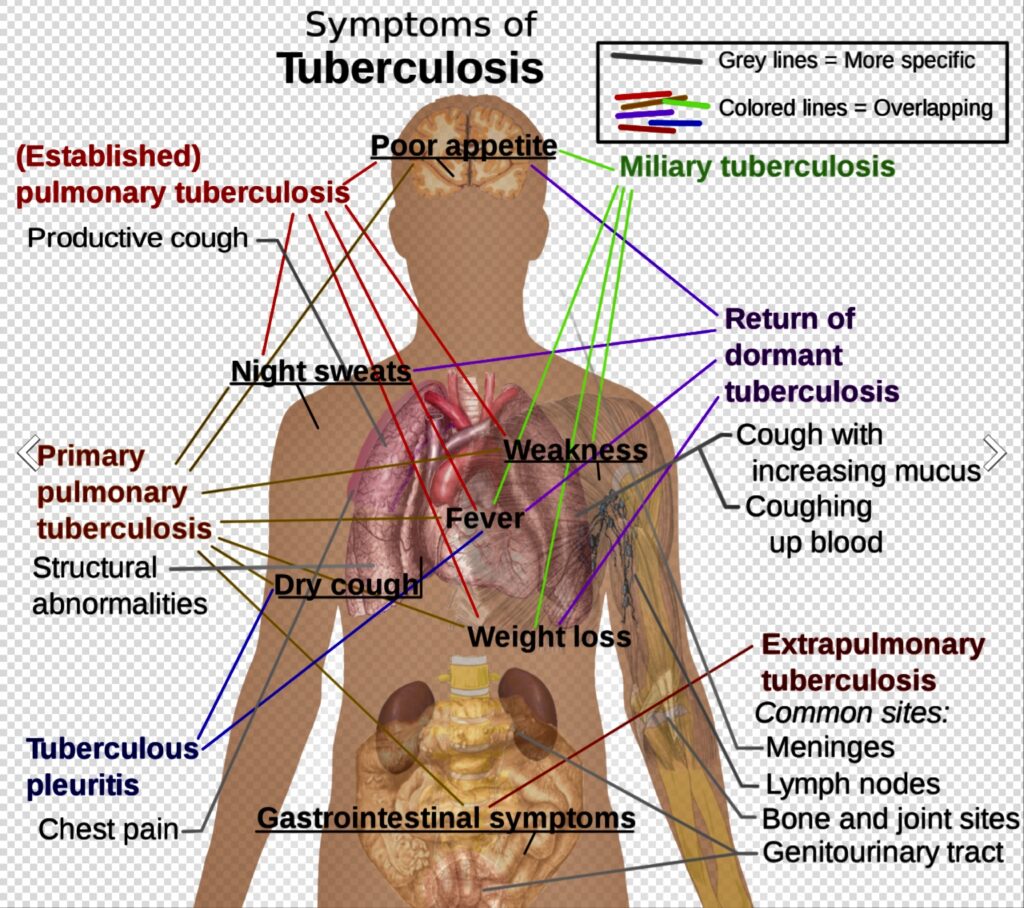

The four most familiar signs of TB, according to health experts, are chronic cough, mild fever in the afternoon and sweating at night, chest and back pain, and progressive weight loss. In more serious or advanced cases, the symptoms are spitting blood, pale and waxy skin, and a hoarse voice.

The disease can occur in two stages: primary and secondary. “In primary TB,” explains Maria Luisa Padilla in Encarta Encyclopedia, “a person has become infected with the TB bacteria but often is not aware of it, since this stage of the disease does not produce noticeable symptoms. Macrophages, immune cells that detect and destroy foreign matter, ingest the TB bacteria and transport them to the lymph nodes where they may be destroyed or inhibited.”

In the early stage, TB is not contagious. “About three weeks after initial infection,” Padilla continues, “bacteria may be inhibited, destroyed, or allowed to multiply. If the bacteria multiply, active primary TB will develop.”

Symptoms of carriers include coughing, night sweats, weight loss, and fever. A chest X-ray may show shadows or fluid collection between the lung and its lining.

If the bacteria are inhibited rather than destroyed, the immune cells form a mass known as granuloma or tubercle. In effect, the immune cells form a wall around inactive bacteria.

“As long as the immune system remains strong, the TB bacteria remain walled off and inactive,” Padilla maintains. “The tubercle gradually collects calcium deposits to form what is known as a Ghon focus. These initial tubercles in the lung usually heal, leaving permanent scars that appear as shadows in chest X-rays.”

At the primary stage of TB, the disease does not progress, but bacteria may remain dormant in the body for many years. If the immune system becomes weakened, the tubercle opens, releasing the bacteria, and the infection may develop into an active disease, known as secondary TB.

In secondary TB, the formerly dormant bacteria multiply and destroy tissue in the lungs. They also may spread to the rest of the body via the bloodstream. Fluid or air may collect between the lungs and the lining of the lungs, while tubercles continue to develop in the lung, progressively destroying lung tissue. Coughing of blood or phlegm may occur. At this secondary stage, carriers of TB can infect others.

Drugs vs. TB

In the past, TB was considered the world’s deadliest disease. Then, in 1944, 21-year-old “Patricia” with progressive, far-advanced pulmonary TB received the first injection of streptomycin. She improved dramatically during the ensuing five months and was discharged in 1947. She was evaluated in 1954 and found to be healthy and the happy mother of three children.

“This injection began the age of modern anti-TB treatment and led – until recently – to dramatic reductions in TB in industrialized countries,” the WHO says.

Other anti-TB drugs are thiacetazone (first introduced in 1946), isoniazid and pyrazinamide (both first tried in 1952), and ethambutol (used for the first time in 1961). The most recent one, rifampicin, was released in 1966.

The success of drug therapy and the declining rates of disease incidence in the middle part of the 19th century instilled a sense of confidence in public health officials that TB could be conquered.

But like a phoenix that rises from ashes, TB has staged a comeback – in a deadlier and more complicated form.

In 1993, the UN health agency declared TB a “global emergency” and created a framework for effective TB control.

In 1994, the name DOTS – for Directly Observed Therapy: Short-Course – was born. The World Bank rated DOTS as “one of the most cost-effective health interventions.” Under the program, which was strongly supported by WHO, each patient was assigned an observer. The task of the observer was to help patients take their medicines regularly and continue with the treatment until they are proven free of the disease.

But it was easier said than done.

“The current TB epidemic is expected to grow worse, especially in developing countries, because of the evolution of MDR (multidrug-resistant) strains and the emergence of AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome), which comprises human immune system and makes them more susceptible to infectious diseases,” notes Anne Platt of the Washington-based Worldwatch Institute.

Multidrug resistant TB

The Philippines has one of the highest rates of MDR-TB in the world. In 2017, 27,000 Filipinos were diagnosed with MDR-TB; it costs up to P160,000 to treat MDR-TB.

The MDR-TB is any strain of the bacteria that is resistant to anti-TB drugs. It generally develops through improper use of TB medication. People being treated for TB normally must take a mixture of drugs over an extended period of time.

If the patients don’t complete their full course of medication, the strongest bacilli surviving in the lungs are given the opportunity to reproduce. Those bacilli will likely be drug-resistant and, if the patient continues to suffer from active TB, can be spread by coughing to other people.

Causes

Poverty has been cited as the major reason for the resurgence of TB. “Overcrowded, impoverished dwellings are its breeding ground, and TB thrives on immune systems weakened by other chronic infections and by malnutrition,” said The Stop TB Initiative 2000 Report.

“Even before the cause of TB was discovered in 1822, thus paving the way to effective drug treatments, the rates of disease were falling in many developed countries because of an improvement in peoples’ standard of living,” the report added.

A significant cause of the dramatic rise in TB cases from the mid-1980s onwards is HIV, the microorganism that causes AIDS. Today, TB is the single biggest killer of people infected with HIV. “HIV and TB form a lethal combination, each speeding the other’s progress,” the WHO says.

HIV weakens the immune system. Health experts say someone who is HIV-positive and infected with TB is 30 times more likely to become sick with TB than someone infected with TB who is HIV-negative.

“There is nothing a person can do to not get TB,” laments the WHO. “You can change your behavior to lower the risk of AIDS, but you cannot stop breathing.”

The international community wants to end TB from this planet by 2030. After all, TB is preventable and curable. But in the Philippines, the number of people with TB continues to increase every year.

“Ending TB requires concerted action by all sectors and all care providers,” the WHO points out. “Everyone has a role to play in ending TB – individuals, communities, businesses, governments, societies. Everyone must join the race to end TB by 2030.”

Meanwhile, the clock is ticking. It’s time to ensure that no one dies of TB anymore!