Text by Henrylito D. Tacio

Photos courtesy of Shutterstock, MSF Ireland, and CDC

What do Manuel L. Quezon and Rene Reqeiustas have in common? Both died of tuberculosis (TB).

Quezon, the first president of the Philippine Commonwealth established under the American tutelage in 1935, was in the United States when he was diagnosed with TB. On August 1, 1944, he died from the disease at Saranac Lake, New York.

Forty-nine years later, on July 24, 1993, Requiestas died at the age of 36 in the Quezon City of TB and other complications brought about by heavy smoking and drinking. The comedian was known for the following films: Cheeta-eh: Ganda Lalaki (1991), Alyas Batman en Robin (1993) and Salawahan (1979).

Despite advanced knowledge in science and the recent discovery of sophisticated drug regimes, TB is still very much around. “TB remains the biggest killer in the world,” says the Davao Doctors Hospital on its website, ddh.com.ph. “The Philippines ranks 8th in the world and third in the Western Pacific Region in terms of the burden of TB. It is the 6th cause of morbidity and mortality in our country with an estimated 270,000 cases detected every year.”

The Department of Health (DOH) said about 75 Filipinos die from TB each day – that’s about three people per hour. This is no wonder the Philippines is joining the international community in observing World TB Day on March 24.

The annual event, which commemorates the date in 1882 when Dr. Robert Koch announced his discovery of the bacillus that causes TB, is a day to educate the public about the impact of TB around the world.

“Each person with active TB can spread the disease to 10 other Filipinos each year! This is alarming since there are between 200,000 and 600,000 Filipinos with active TB. Multiply this by 10, and just imagine how much TB is being spread yearly,” deplores Dr. Willie T. Ong, who writes a regular column for a national daily.

“Tuberculosis is perhaps the greatest killer of all time,” wrote Dr. Frank Ryan, author of Tuberculosis: The Greatest Story Never Told. “Tuberculosis rose slowly, silently, seeping into the homes of millions, like an ageless miasma. Once arrived, TB stayed (and became) a stealthy predator.”

The tenacious TB bacillus has preyed on people since antiquity. TB-induced skeletal deformities point to the disease’s existence as early as 8000 BC.

“Year after year, century after century, it tightened its relentless grip, worsening with wars and famines that reduced people’s resistance, infecting virtually everyone but inexplicably sparing some while destroying others,” wrote Dr. Ryan in his book.

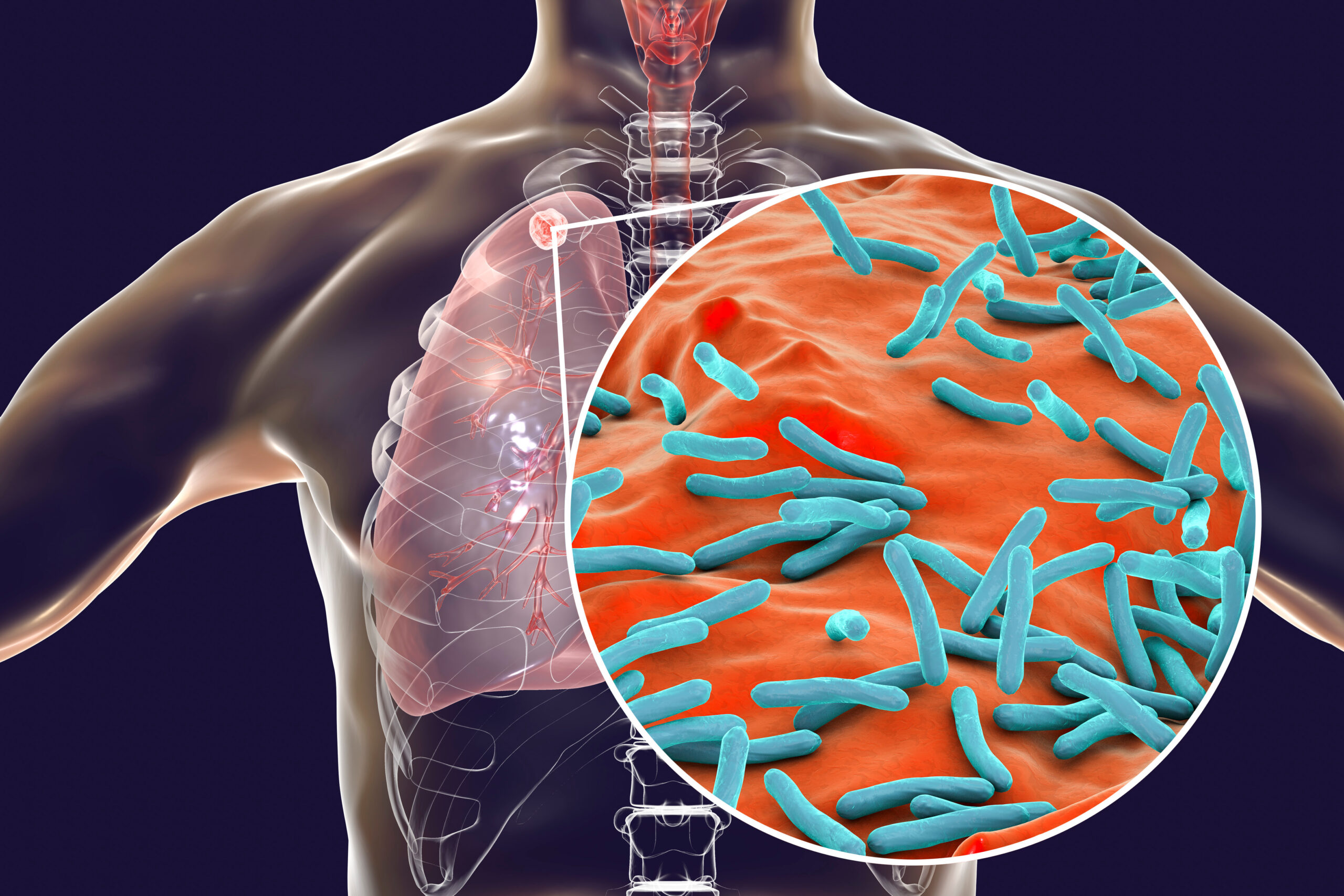

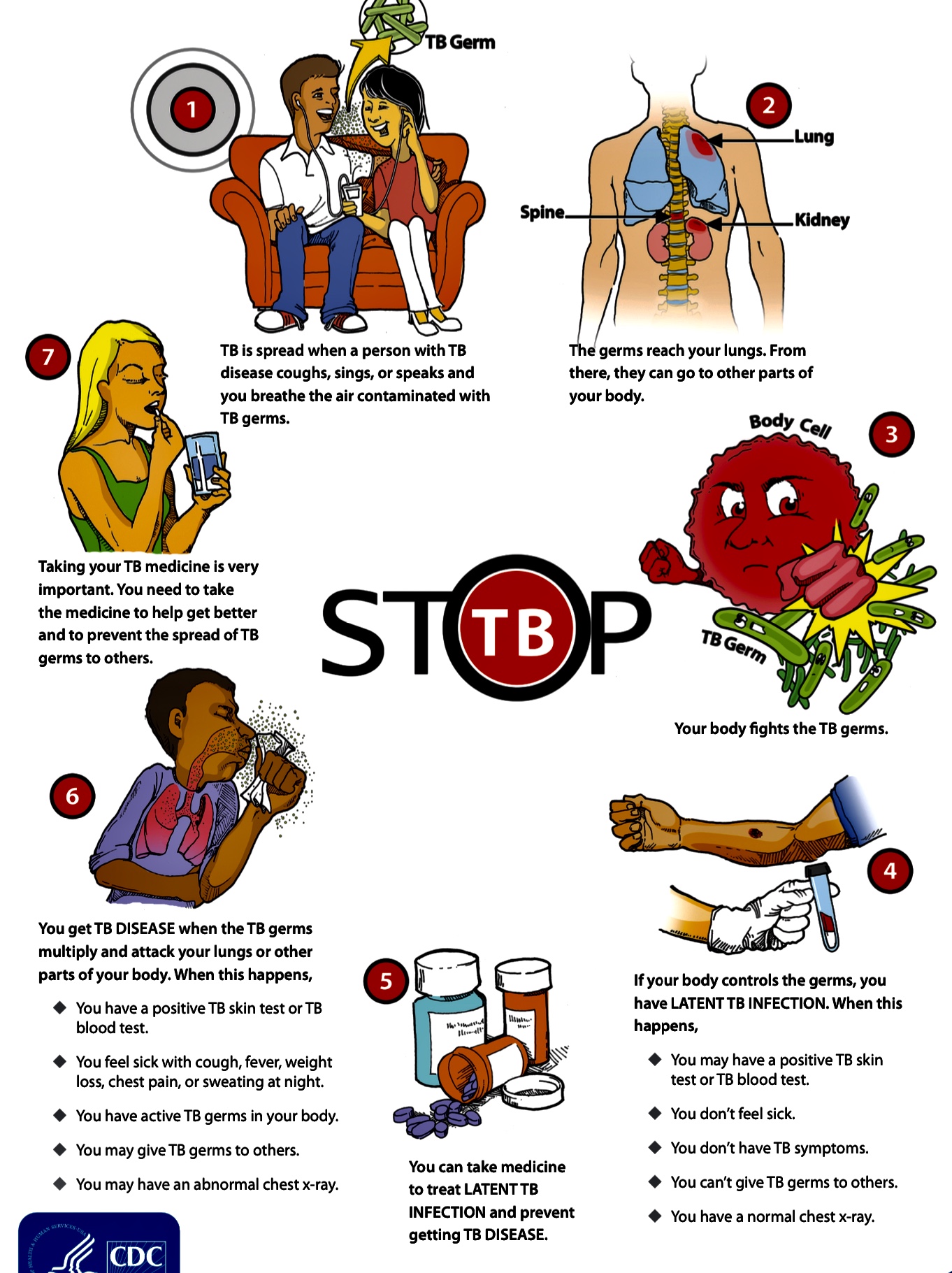

Dr. Ong, who co-authored the book with his wife, Dr. Liza Ong, Doctors’ Health Tips and Home Remedies, defines TB as “an infection caused by bacteria that usually affects the lungs.” These bacteria, called “Mycobacterium tuberculosis,” can transfer to another person through tiny droplets spread by coughing and sneezing.

This is how TB attacks the lungs: Airborne TB bacteria (bacilli) are inhaled into the lungs’ small tubes. Macrophages, a kind of defensive cell, attack the particles, killing or surrounding them. Other immune cells surround particles in hard lumps called tubercles, making bacilli harmless.

If the body’s immune system weakens, bacilli can escape from the tubercle. A weakened immune system can’t neutralize the bacilli. They multiply and penetrate blood vessels, spreading diseases throughout the body.

In the Philippines, TB is common among high-risk groups such as the elderly, urban poor, smokers, and those with compromised immune systems such as people living with HIV, malnutrition, and diabetes.

In the past, TB was considered the world’s deadliest disease. Then, in 1944, 21-year-old “Patricia” with progressive, far-advanced pulmonary TB received the first injection of streptomycin. She improved dramatically during the ensuing five months and was discharged in 1947. She was evaluated in 1954 and found to be healthy and the happy mother of three children.

“This injection began the age of modern anti-TB treatment and led – until recently – to dramatic reductions in TB in industrialized countries,” the Geneva-based World Health Organization (WHO) points out.

TB can either be latent or active. In latent TB conditions, the TB bacteria have already infected the patient’s body, yet they are still in their inactive state. There are no signs and symptoms, and it is not contagious.

If you are diagnosed with active TB, then you must absolutely take anti-TB medicines. “There are no ifs and buts,” Dr. Ong says. “It’s for your own good and for the good of the people around you. If you don’t take the medications, then you will be infecting an average of 10 persons in a year, including your loved ones and children.”

According to Dr. Ong, the treatment for TB is a bit more complicated compared to ordinary infections “since it will take approximately six months to completely eradicate the bacteria.” In cases where the infection is severe, it may take about nine months of treatment.

Only a doctor can give you the correct treatment, so you better see one. “Never self-medicate,” Dr. Ong reminds. “This is the worst thing you can do. It will only strengthen the bacteria inside you and make you resistant in one tablet.”

Dr. Ong suggests that those who are undergoing treatment stay at home during the first three weeks of treatment. “Don’t go to school, work, or come in close contact with people,” he says. “Your saliva and phlegm can infect others.”

He also recommends that they wear a face mask during the first three weeks of treatment. “Cover your mouth with a tissue when you cough, sneeze or laugh too hard,” Dr. Ong urges. “Then throw the tissue away in a sealed container.”

As a sort of reminder, all TB medications must be taken one hour before meals. “It is ideal not to break the dose of the drug,” Dr. Ong reminds. The patient needs to see his doctor to undergo blood tests to check for possible liver side effects of the drugs taken.

Side effects aren’t common, but some TB medicines can occasionally be harmful to the liver, he says. In addition, the color of the urine will change from yellow to orange. But don’t worry; the change of color is “a normal reaction to the treatment course.”

Dr. Ong suggests that you need to consult your doctor once you experience any of the following: nausea, vomiting, loss of appetites, yellowing of the skin, or fever of more than three days.

The most important thing: “Complete the 6- to 9-month course of your medicines,” Dr. Ong declares. “Do not stop your medicines without your doctor’s permission. Doing so will cause the TB bacteria to mutate and come back in a stronger and more virulent form.”

In 2011, the WHO regional office reported that about 10,600 Filipinos have multi-drug resistant TB (MDR-TB). By 2015, MDT-TB cases went to 15,000.

Health experts say “treatment outcomes for MDR-TB are typically worse than those for patients with drug sensitive TB, in significant part due to the length of treatment and the potential for adverse effects from second-line medications.”

There is still much to be done. “Many factors still need to be addressed such as reducing the stigma of TB patients, and increasing the public’s awareness of the disease, especially the need for treatment,” Dr. Ong points out. “Some infected TB patients still refuse treatment and continue to pose a danger to people around them.”

The international community wants to end TB from this planet by 2030. After all, TB is preventable and curable. But in the Philippines, the number of people with TB continues to increase every year.

“Ending TB requires concerted action by all sectors and all care providers,” the WHO points out. “Everyone has a role to play in ending TB – individuals, communities, businesses, governments, societies. Everyone must join the race to end TB by 2030.”

Meanwhile, the clock is ticking. It’s time to ensure that no one dies of TB anymore.