Text by Henrylito D. Tacio

Photos by Julius Paner

By now, you have probably heard of ecotourism.

The Ecotourism Society defines ecotourism as “purposeful travel to natural areas to understand the culture and natural history of the environment, taking care not to alter the integrity of the ecosystem while producing economic opportunities that make the conservation of natural resources beneficial to local people.”

In a workshop conducted at Los Baños, Laguna, some years back, ecotourism is defined as “an environmentally sound tourism activity in a given ecosystem yielding socio-economic benefits and enhancing natural and cultural diversity conservation.”

Actually, ecotourism refers to the business of nature travel. Among its main focus are the following: environmental awareness and activities range from purely educational (such as studying ecosystems), hobby-oriented (like photo expeditions into exotic habitats), or thrill-seeking (mountain climbing comes to mind).

In time, community-based ecotourism (CBET) came into existence. CBET is a program where the operation and management of ecotourism sites are handled, undertaken, and controlled by the community where those sites are located.

If you happen to come to Santa Cruz in Davao del Sur, you can visit seven prevailing sites as CBET attractions, according to Julius R. Paner, the town municipal tourism officer. “The community came to us and suggested these sites,” he explained. “Our office validates these sites by actual visit site, exploration and documentation.”

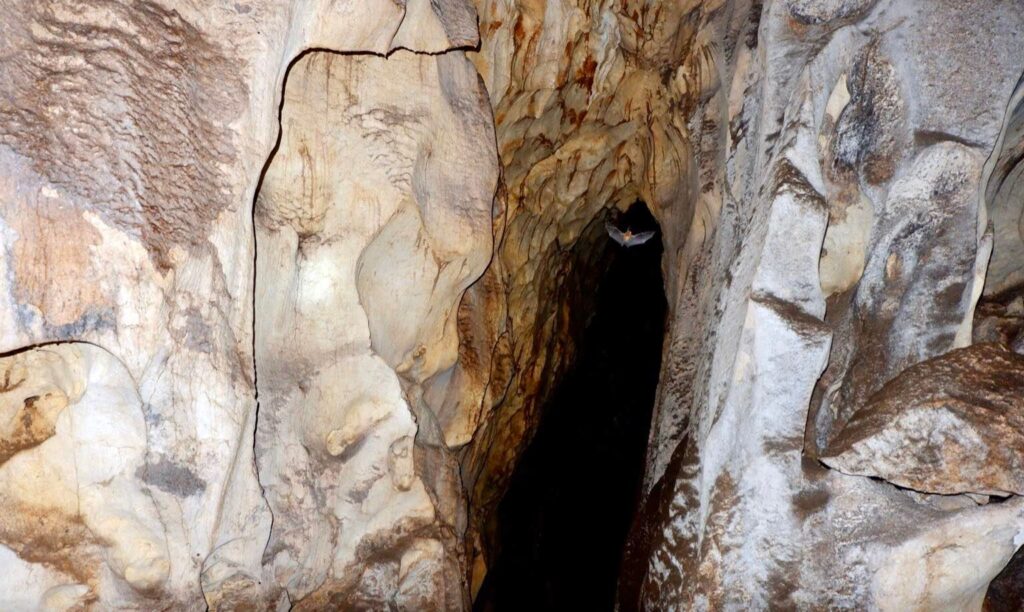

The seven ecotourism sites are: the Mount Apo Trail and Tomari Waterfalls, both in barangay Sibulan; the Bagobo Cultural Village in barangay Tibolo, the Sinoron Ecotourism Park in barangay Sinoron, Mount Loay in barangay Zone 2, the Bamboo Peak in barangay Jose Rizal, and the Saliducon Cave in barangay Saliducon.

According to Paner, the community operates the site. “That means they do everything from tourist registration, collection of fees, orientation, deployment of tour guides, monitoring of visitors and maintaining cleanliness of the sites,” he explains.

In every site or attraction, there is a corresponding legitimate Peoples Organization (PO). “The PO is the main actor of the show, which in our case belong mostly to Indigenous Peoples (IPs) because almost all of these sites are located within the Bagobo-Tagabawa Ancestral Domain,” Paner says.

Mount Loay

Bamboo Peak

The government, which is represented by barangay officials, only provides minimal assistance like traffic control and peace and order maintenance. These barangay officials see to it that the operation is smooth.

Unlike those on the beaches, where people enjoy swimming, ecotourism caters to a different kind of attraction. What the sites offer is their natural beauty which cannot be seen in urban settings.

“Ecotourism means enjoying what is available on the site,” Paner says. “This also means that aside from the tourism activities, the community will also integrate conservation and preservation of the environment by making sure that no flora and fauna will be taken out from the areas.”

Not only that. The community will also religiously implement solid waste management. Regular tree growing is also part of their responsibility.

“The beauty of CBET is that the community, particularly the locals, will be able to control everything, thus, everything becomes sustainable,” he points out. “Since they are gaining income out of its beautiful natural attractions, they will exert all-out efforts to maintain its natural state and protect it.”

After all, people come to visit these sites because of the natural beauty of the areas.

“Conservation should be over and above everything in terms of ecotourism, which is why everybody have stake of this one, including visitors and guests,” Paner urges. “They should follow guidelines and policies such the mandatory hiring of guides, make sure that not a single trash is left in the sites and should follow the ‘Leave No Trace’ principles.”

Recently, Sta. Cruz has been gaining so much popularity because of its natural attractions, which can be considered as world-class.

Banking on these sites, the local government facilitates training such as tourism awareness, tour guiding, tour packaging, and other capability-building activities among stakeholders.

“We also do marketing and promotions, as well as consolidating statistics reports, which are submitted to the Department of Tourism,” he says.

As a result, Sta. Cruz became a popular destination when it comes to ecotourism. “We are successful in packaging the place for practically all audiences and millennials by selling experience more than just the site,” Paner says.

Tomari Waterfalls

Saliducon Cave

This led to the creation of the tagline: “Spectacular Sta. Cruz.”

Other reasons for the popularity of Sta. Cruz as a top ecotourism destination in Davao del Sur: Geographically, Sta. Cruz is the closest town to Mindanao’s main gateway, Davao City. More importantly, it has established a good partnership with the media, who have been helping the municipality create good stories about the place.

Before the pandemic happened, around 130,000 tourists – on average – came to visit the town every year. “Sixty percent of our visitors and guests were domestic tourists, 38% locals, and close to 2% foreigners,” Paner admits.

Paner considers 2022 as a “horrible year.” Only 11,000 tourists came, as per record showed, as Sta. Cruz – like other towns in the region – was under the modified, enhanced community quarantine (MECQ).

Last year, tourism regained momentum. “We have catered close to 100,000 arrivals,” he says. “This is a good number already considering that there were months in 2021 declared under MECQ.”

Aside from visiting those ecotourism destinations, there are other activities visitors can do. “We have created a venue for a wider range of markets, which means anything you want to do outdoors, you can do it all in Sta. Cruz,” Paner says. “Biking, trail running, camping, rappelling, hiking, caving, swimming, snorkeling, diving, bird watching, beach frolicking, river tubing, educational tours, cultural immersion, team building, forest bathing; name it and we can cater it all here.”

Sta. Cruz has indeed come a long, long way as far as ecotourism is concerned. Looking back, it wasn’t that easy. “CBET is actually not very easy to start with as a tourism program,” Paner says. “A lot of coordination has to be undertaken and there are national government agencies to be considered like the National Commission for Indigenous Peoples (NCIP) and Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). It is a tedious process, in which the majority of the tasks should be exerted by our level in the tourism office. Thankfully we have overcome all them.”

Among the challenges they encountered, they addressed them collaboratively by involving all parties in laying out practical solutions. “For example, if the issue is about solid waste management and biodiversity related,” he says, “we always tap the expertise of the DENR people to help us resolve the matter.”

The result of these collaborations and hard work can now be seen. “Personally,” Paner says, “I consider this program a success and sustainable because we involve the community in the implementation and we integrate environmental conservation. That is the most important component of CBET – community and environment.”

Right now, Paner and his team are focusing their energy on developing the so-called Cruise Tourism in three barangays: Bato, Tuban, and Tagabuli. “We are about to launch this by opening our Floating Restaurant and Offshore Tour,” he says.

Another tourism plan is “to intensify visibility and accessibility of all our attractions through infrastructure support and directional signage to make it more tourist-friendly.”

Sta. Cruz, founded on October 5, 1884, is the second oldest municipality in Davao Region. The record goes to Caraga, in Davao Oriental, which was officially founded as a town in 1861.