Text By Henrylito D. Tacio

Illustrations from WHO

Six summers ago, 5-year-old Kathy started coughing hard every night. Her mother, Sarah, took her to a clinic and asked for an antibiotic. The doctor prescribed azithromycin, and Kathy seemed to improve, but a month later, she had another coughing fit. The doctor put her on a different antibiotic, clarithromycin.

More illnesses followed – ear infections, coughs, colds, runny nose. In one year, Kathy was given ten different courses of antibiotics. Then, when she was nine, she was struck down by a terrifying new illness. Her temperature soared to nearly 40 degrees, and she was having trouble breathing. When Sarah coughed, her phlegm was mixed with blood.

Sarah rushed her daughter to a hospital, where doctors diagnosed bacterial pneumonia and prescribed more antibiotics: azithromycin plus amoxicillin/clavulanic acid. When Kathy showed no sign of improvement, tests revealed that she had been hit with a strain of Streptococcus pneumoniae resistant to azithromycin and other common antibiotics.

Doctors had only one option left – vancomycin, a potent antibiotic given intravenously. Fortunately, the drug worked, and Kathy recovered quickly. “Based on her medical history, Kathy was a prime candidate for a resistant bacterium,” the doctor who took care of her told this author.

Antibiotics remain the world’s most effective weapon against disease-causing bacteria, with the power to save lives and prevent illness. In 1969, an American Surgeon General told the United States Congress: “The time has come to close the book on infectious diseases.” Because of this, research budgets were slashed, and medical students were discouraged from specializing in such illnesses.

Dr. Bernard Fields, a Harvard microbiologist who went through American medical schools in the 1960s, recalled being told by his mentors: “Don’t bother going into infectious diseases.”

“The perception was that we had conquered almost every infectious disease,” points out Dr. Thomas Beam of the Buffalo, New York, VA Medical Center in a press statement. The poliovirus had been tamed by the Salk and Sabin vaccines. The smallpox virus was virtually gone. The parasite that caused malaria was in retreat. Once deadly illnesses, including diphtheria, pertussis (whooping cough), and tetanus, seemed like quaint reminders of a bygone era.

Science was sure the real challenges would be in the conquest of cancer, heart disease, and other chronic ailments. Instead, “medicine’s purported triumph over infectious disease has become an illusion,” writes Dr. Sherwin Nuland in his bestselling How We Die.

Drug-resistant bacteria

But it seems the medical world declared victory too early and went home too soon. These days, every disease-causing bacterium has versions that resist at least one of medicine’s 100-plus antibiotics.

“Some of the world’s most common – and potentially most dangerous – infections are proving drug-resistant,” the World Health Organization (WHO) admits. Among those that defy antibiotics are Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, and Streptococcus pneumonia.

The United Nations health agency calls this phenomenon antimicrobial resistance (AMR). It occurs when microorganisms change after exposure to antimicrobial drugs such as antibiotics. “It is a serious global health concern as it comprises the ability to treat infectious diseases, as well as undermines many other advances in medicine in both human and animal health,” the WHO says.

In 2014, an estimated 700,000 cases of AMR from various parts of the world were reported, according to Antimicrobial Resistance: Tackling a Crisis for the Health and Wealth of Nations. By 2050, the number is expected to balloon to 10 million.

In the Philippines, the 2015 Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Program report of the Department of Health said that “organisms commonly involved in deadly human infections are responding less and less to antibiotics.”

In an article that came out in Philippine Daily Inquirer, Anne A. Jambora wrote: “Bacteria, viruses and some parasites can now stop antimicrobial medications, such as antibiotics and antivirals, from working against them. Standard treatment then becomes ineffective, and soon, in an event of a post-antibiotic era, even the simplest injury or a minor wound could become life-threatening.”

Reasons for emergence

There are several reasons there is a sudden surge of new bacteria and viruses that resist antibiotics. Abuse of antibiotics has been cited as one of the main culprits. “Essentially,” Dr. Lee Green, a family practitioner at the University of Michigan, was quoted as saying by Newsweek, “we have a tradition of prescribing antibiotics to anybody who looks sick.”

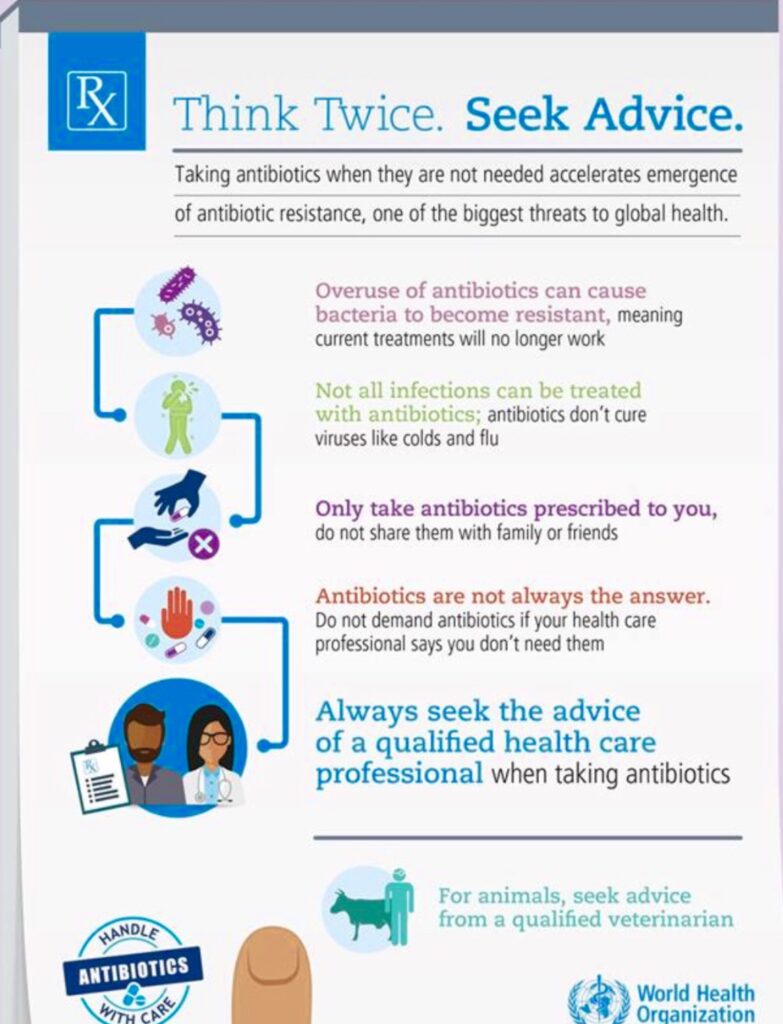

According to WHO, not all infections can be treated with antibiotics. Those caused by viruses like cold and flu cannot be cured by antibiotics. “Do not demand antibiotics if your health care professional says you don’t need them,” it urges.

But “in many countries, antibiotics are available without doctor’s prescription, which lets patients diagnose and dose themselves, often inappropriately,” Time journalist Michael D. Lemonick added.

“The overuse of antibiotics – especially taking antibiotics even when they’re not the appropriate treatment – promotes antibiotic resistance,” the US-based Mayo Clinic explains. “Antibiotics treat bacterial infections but not viral infections.”

But even when doctors dispense antibiotics properly, there is no guarantee they’ll be used that way. This is where another reason comes in: misuse. Several studies have shown that a third of all patients fail to use the drugs as prescribed. In his special report, Lemonick wrote: “Patients frequently stop taking antibiotics when their symptoms go away but before an infection is entirely cleared up. That suppresses susceptible microbes but allows partially resistant ones to flourish.”

This has been fully explained by Sally Davies, the United Kingdom’s Chief Medical Officer. In her book, The Drugs Don’t Work, the author describes how bacteria become resistant to drugs when a person doesn’t take antibiotics for long enough.

“If the drugs are not given enough opportunity to fully kill the bacteria it may survive while also learning how to resist future treatment with the same drug,” Davies wrote. “This is why it is important that antibiotics are only taken exactly as prescribed by a trained medical professional.”

Still another culprit: agriculture. “Since the introduction of penicillin in the middle of the 20th century, antimicrobial treatments have been used not only in human medicine but in veterinary care as well,” the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) reports. “At first, they were utilized to treat sick animals and to introduce new surgical techniques, making it possible, for example, to perform caesarian sections in cattle on farms.

“With the intensification of farming, however, the use of antimicrobials was expanded to include disease prevention and use as growth promoters,” FAO added.

Estimates of antibiotic consumption in global agriculture vary due to poor surveillance and data collection in many countries, ranging from around 63,000 tons per year to over 240,000 tons per year.

High-tech farmers have learned that mixing low doses of antibiotics into cattle feed makes the animals grow larger,” Lemonick wrote. “Bacteria in the cattle become resistant to the drugs, and when people drink milk or eat meat, this immunity may be transferred to human bacteria.”

According to Dr. Enrique “Eric” Tayag of the Department of Health (DOH), when food is mixed with antibiotics, AMR may result. “There is an animal-to-person contamination, and person-to-person transmission,” the former assistant health secretary was quoted as saying. “So now, we’re looking at animal health, food health and human health.”

Global political response

The WHO considers AMR as “one of the biggest threats to global health, food security and development today.” To address the looming antibiotic resistance disaster, a global political response similar to the way the world has reacted to climate change or acquired immune deficiency syndrome is needed.

“Of course (with antibiotic resistance), we have many technical issues still to solve, and medical issues, as well but it’s foremost a political issue,” Sweden’s Minister of Public Health Gabriel Wikstrom told Inter Press Service.

The “business-as-usual” scenario must be stopped at all costs. “What is clear is that all countries around the world need to stop treating antibiotics as if they are sweets,” declared Lord Jim O’Neill, Chairman of the Review on Antimicrobial Resistance of the United Kingdom. “It’s true in humans, and it’s true in agriculture.”

Dr. Gundo Weiler, WHO Representative in the Philippines, agrees. “Antimicrobial resistance is a complex problem that requires concerted action across all sectors. While it is a complex issue, there are also simple solutions that each of us can do such as seeking advice from a healthcare professional before taking antibiotics; never sharing antibiotics with loved ones; and preventing infections at the start.”

In the Philippines, Administrative Order No. 42 s. 2014 created the Inter-Agency Committee on Antimicrobial Resistance to formulate and implement the National Action Plan Against AMR and to rationalize, harmonize, streamline, integrate, and unify the efforts of government agencies to address the problem.

“The battle against AMR is continuous and we cannot relent,” pointed out Dr. Butch Rector, MSD medical director. “It is difficult, but with concerted effort – from patients and doctors, to the government as well as the private sector – we can be optimistic of a world finally free from AMR.”