Text by Henrylito D. Tacio

Photo: Stony Brook Medicine

FORMER American Vice-President Dan Quayle never knew what hit him. He was promoting his memoir, “Standing Firm,” when he experienced severe shortness of breath and had trouble finishing his speeches.

He thought it was just a bad cold and didn’t bother to see a doctor. It was a bad decision. On November 27, 1994, he was brought to the emergency room at the Indiana University Medical Center. The doctor’s diagnosis: “walking pneumonia.”

The 47-year-old Quayle was sent home and thought it was over. The following day, however, his breathing difficulty worsened, and he was admitted to the emergency room again. After further tests, doctors re-diagnosed his condition as a “pulmonary embolism.”

“You’d be surprised how often a pulmonary embolism is missed, even with most skilled physicians,” Quayle said in a statement following his release. “Misdiagnosis is common. I was lucky…very lucky.”

He was indeed very lucky. According to the National Institute of Health, more than 600,000 people in the United States have a pulmonary embolism each year, and more than 60,000 of them die. Experts say that most of those who die do so within 30 to 60 minutes after symptoms start.

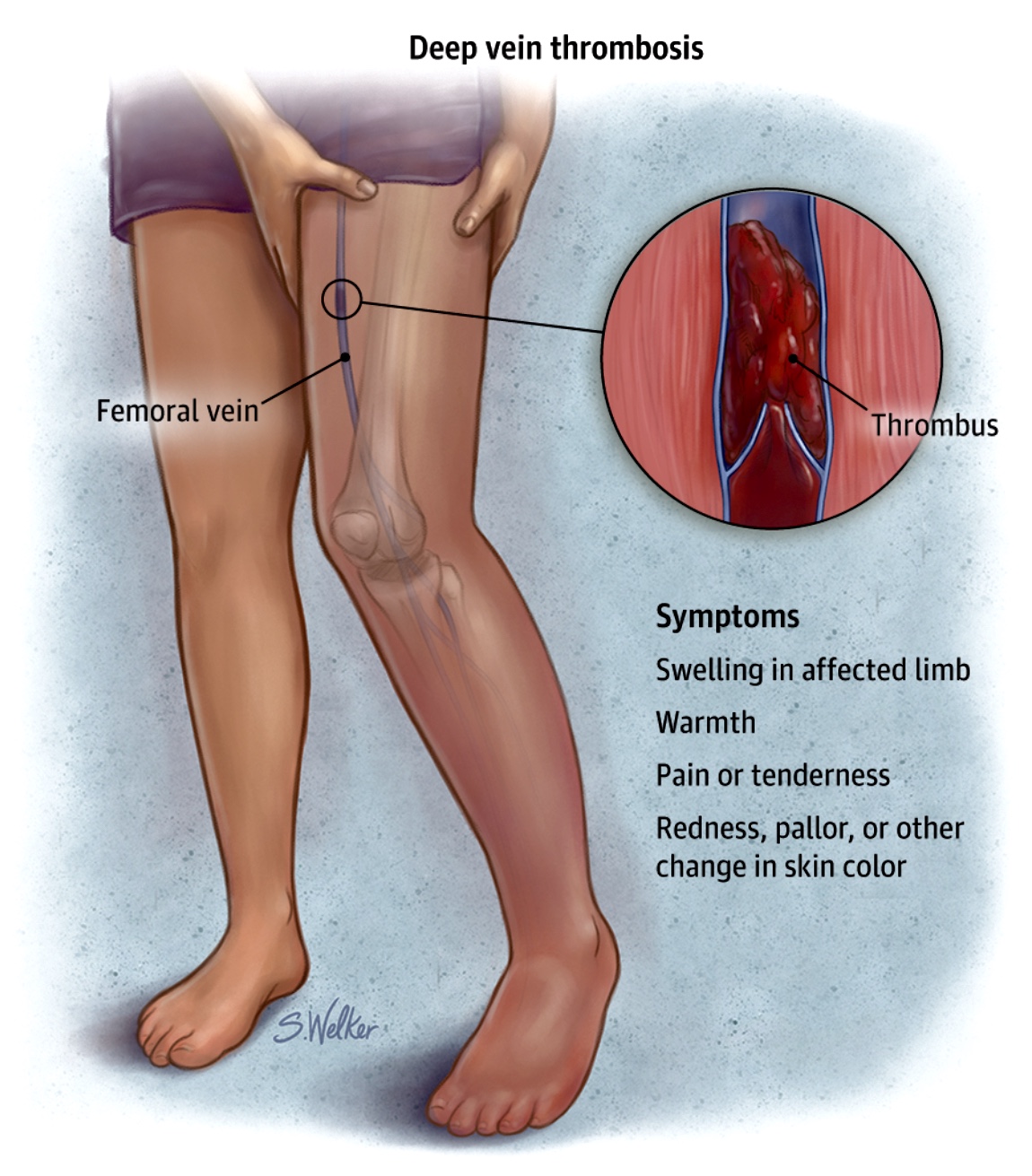

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a complication of a medical condition called deep vein thrombosis (DVT), in which a blood clot forms inside the deep veins of the lower legs, thighs, or pelvis.

Although there is no single, simple cause, a DVT may be due to injury to the lining of the vein, changes in the pattern of blood flow (like compression, turbulence, and stagnation), an increased tendency for blood to clot, and for that clot not to naturally dissolve again.

“One out of three causes usually does not trigger a DVT and three out of three is fortunately uncommon,” says Dr. Rene De Jongh, South Asia medical director of the assistance services of International SOS in Singapore.

While DVT has given much attention in the United States and Europe, such is not the case in the Philippines. “It is difficult to detect travel-related DVT because we don’t screen, and we don’t know actual risk, and (diagnosis) is less accurate in asymptomatic people,” explains Dr. Teresa B. Abola, a cardiologist with the Philippine Heart Center.

This must be the reason why the public is not aware of the potential health risk of blood clots. Clotting the blood is “nature’s way of trying to prevent bleeding,” says Dr. Rafael Castillo, a cardiologist, and chair of the department of medicine of the Manila Sanitarium and Hospital. But when nature’s protective mechanism goes awry, there is a danger of blood clots resulting in a DVT.

Health authorities claim DVT is instigated by prolonged periods of physical immobility. “If a person is just sitting around and not moving, say, during a very long flight, he may risk himself developing a DVT,” says Dr. Gary Raskob, dean of the college of public health at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center.

How does DVT happen? It starts with blood clots forming in the veins of the legs during hours of immobility (that is, long-haul flights). When mobility resumes (for instance, once a passenger deplanes), the clots can break free of the vein and travel to the lungs, causing a pulmonary embolism that may result in death.

In a study published in Aviation Space and Environmental Medicine, 87 percent of identified DVT cases identified occurred following either a return trip or after an outward journey involving long trips made up of sequential flights. In France, researchers from the Hospital Pasteur claim that air travelers who sit for more than five hours on planes are more likely to develop blood clots in their legs than non-travelers.

At Narita hospital near Tokyo’s International Airport, records show an average of 100 to 150 passengers is treated for DVT immediately upon arrival each year; three to five percent of those die.

“Only one percent of air passengers suffers from DVT,” Dr. Farrol Kahn, head of the United Kingdom-based Aviation Health Institute. “Other passengers who have predisposing factors have a higher risk of between five to six percent. About 10-15 passengers on a jumbo jet (Boeing 747) could develop a DVT.”

There are multiple risk factors for developing blood clots in the leg, health authorities claim. There are genetic risk factors and then superimposed on that are risk factors such as having surgery or trauma. “It is likely that most individuals who develop a DVT during or after a long plane flight also have additional risk factors,” maintains Dr. Raskob.

This has been confirmed in a study that appeared in the British Journal of Hematology. It concluded that the risk of DVT was only increased in long-haul travelers if one or more additional risk factors were present.

According to Dr. Walter Fister, whose special interest is in public health and works with the Mount Elizabeth Medical Centre in Singapore, the risk of DVT is greater in the following people: older persons (over 40 years of age); have had previous blood clots; with a family history of blood clots or an inherited clotting tendency; suffering from or who have had treatment for cancer; with certain blood diseases; being treated for heart failure and circulation problems; have had recent surgery especially on the hips or knees; and pregnant.

Obese, smokers, and tall people are also at risk. “Women who take birth control pills or undergoing hormone replacement therapy are also likely to suffer from a DVT because estrogen is a risk factor for clotting,” informs Dr. Raskob.

Almost half the time, DVT strikes without warning. “Up to 50 percent of all DVT cases are unknown — most likely even higher – since most people may not experience any symptoms at all,” says Dr. Fister. “Most likely lots of people get DVT without any knowledge and where the clot forms and dissolves all on its own and they are none the wiser.”

In most instances, doctors misdiagnose DVT. “The symptoms and signs are very ‘non specific,’ meaning they may be caused by many different medical conditions,” explains Dr. Raskob. “DVT is frequently mistaken for other conditions such as muscle strains, skin infections, heart failure, dependent edema and ruptured Baker’s cyst,” informs Dr. Haizal bin Haron Kamar, associate professor in medicine and cardiology at the University of Malaya in Kuala Lumpur.

In instances where symptoms do present themselves, they may include deep muscle pain, muscular tenderness, swelling or tightness, discoloration of the affected area, and skin that feels unusually warm. “More often than not, these classical symptoms are found in only a minority of cases,” says Dr. Jongh.

Pulmonary embolism, DVT’s fatal complication, is also hard to diagnose. Just as the symptoms and signs of a DVT are not unique to it, the presenting or warning signs of a PE are not characteristic either, as some, many or none of the following may be evident: sweating, fainting, feeling short of breath, feeling pain or tightness in the chest, having a fast pulse, and coughing up blood-stained phlegm, among others,” says Dr. Jongh.

“DVT does not occur during the flight but after the flight hours or days later,” reminds Kahn. “Even two to three weeks later, anyone who experienced some symptoms should consult their doctors. They should tell them that they have been on a flight and ask to check them for possible DVT.”

Symptoms alone are not the only basis for a person to be diagnosed with DVT. Dr. Mark Ebell, an associate medical professor of the Michigan State University, says the most commonly used diagnostic tests for DVT include ultrasound (test blood flow through the veins), constant venography (monitoring the progress of dye injected into the bloodstream), chest x-ray/scan (for people with breathing difficulties), arterial blood gas (to measure the amount of oxygen and other gases in the blood), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).