Text and Photos by Henrylito D. Tacio

No, it’s not dwindling land areas that pose the biggest threat to food security, it’s water shortage.

“Many well-informed individuals see a future of water shortages, but few have connected the dots to see that a future of water shortages will also be a future of food shortages,” said Lester R. Brown, the president of the Washington, D.C.-based Earth Policy Institute.

“Water shortages lag only climate change and population growth as a threat to the human future,” said Brown in an exclusive interview by this author. “The challenge is not to get enough water to drink, but to get enough water to produce our food. We drink, in one form or another, perhaps 4 liters of water per day. But the food we consume each day requires 2,000 liters of water to produce, or 500 times as much.”

A closer look at the available statistics proves him right. Agriculture is by far the biggest consumer of water around the world. In thickly-populated Asia, agriculture accounts for 86% of the total annual water withdrawal, compared with 49% in North and Central America and 38% in Europe.

“Agriculture is where future water shortages will be most acute,” wrote Michael S. Serrill in “Time” some years back.

Rice is a case in point. “Water has contributed most to the growth in rice production for the past 30 years,” said the Laguna-based International Rice Research Institute (IRRI). Irrigation-farmed rice draws heavily on the resource.

In his book, “Water: The International Crisis,” Robin Clark reports that an average farmer needs 5,000 liters of water to produce one kilogram of rice. “Rice growing is a heavy consumer of water,” agrees the IRRI report, “Water: A Looming Crisis.”

The IRRI report projected that most Asian countries will have severe water problems by 2025. This water shortage could seriously threaten rice production in the region.

This is bad news for Filipinos who consider rice as their “deepest comfort food.” Each day, about 31,450 metric tons of rice are consumed by Filipinos, according to Secretary Emmanuel F. Piñol of the Department of Agriculture.

“The link between water and food is strong,” Brown reminded. British author John Robbins, the man behind “Food Revolution,” has managed to document the robust connection between these two resources. To produce one pound of lettuce or one pound of tomatoes, 23 gallons of water is needed.

For one pound of potatoes, 24 gallons of water is needed; 25 gallons for one pound of wheat, 33 gallons for one pound of carrots, and 49 gallons for one pound of apples, according to Robbins.

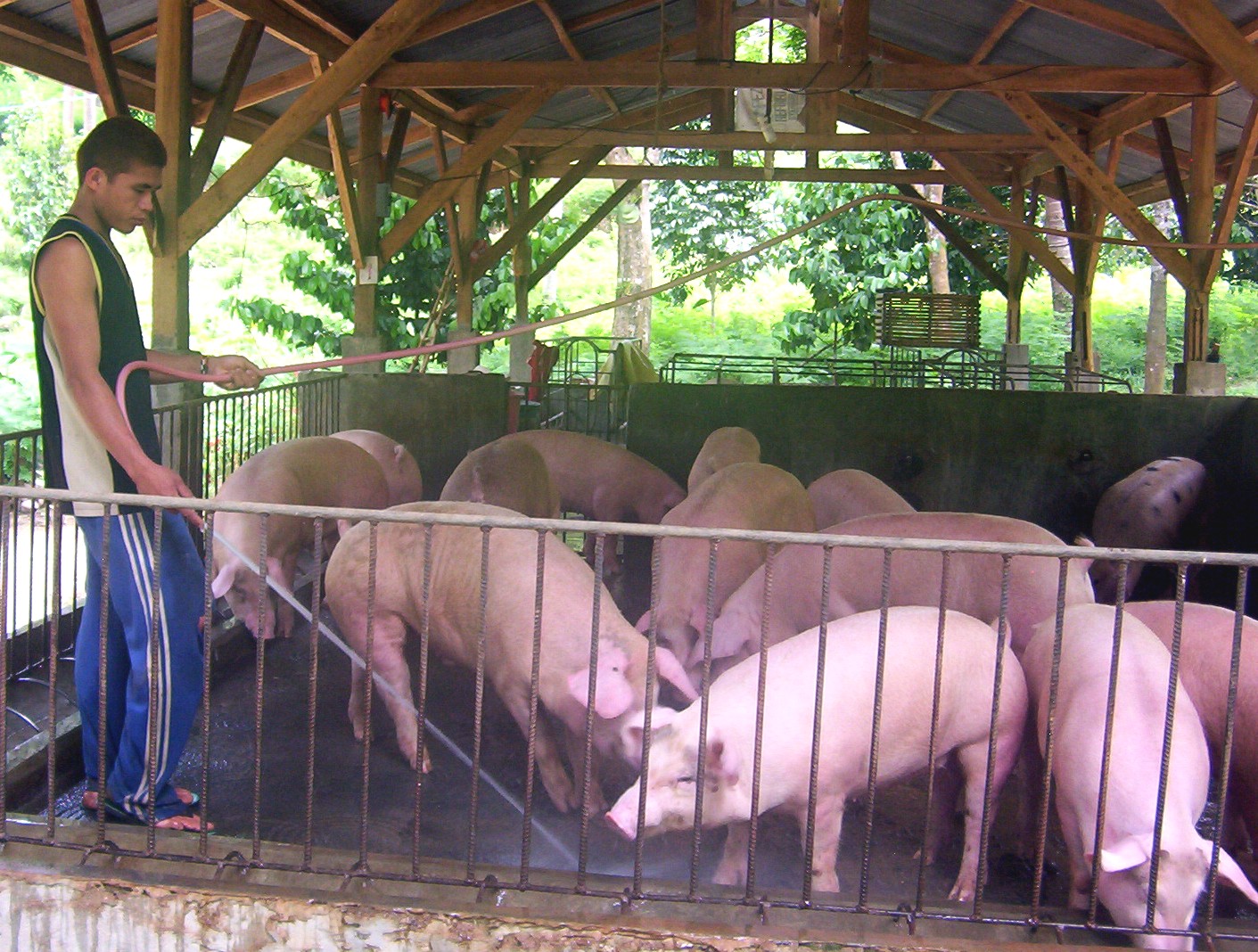

Meat production also consumes a lot of water. “Agriculture uses about 70% of the world’s available freshwater, and one-third of that is used to grow the grain fed to livestock,” the Worldwatch Institute reports.

Beef, the meat used in most fast food outlets, is by far the most water-intensive of all meats. “The more than 15,000 liters of water used per kilogram is far more than is required by a number of staple foods, such as eggs (3,300 liters per kilogram), milk (1,000 liters), or potatoes (255 liters),” the Worldwatch Institute says.

The US Department of Commerce 1992 Census of Agriculture’s Farm and Ranch Irrigation Survey, published in 1994, reported that one pound of pork needs at least 1,630 gallons of water to produce, but in contrast, one pound of beef requires 5,214 gallons of water.

“Producing beef is much more resource-intensive than producing pork or chicken, requiring roughly three to five times as much land to generate the same amount of protein,” the Worldwatch Institute points out.

Around the world, more than 40% of wheat, rye, oats, and corn production is fed to animals, along with 250 million tons of soybeans and other oilseeds. “Feeding grain to livestock improves their fertility and growth, but it sets up a de facto competition for food between man and people,” the institute says.

Global meat consumption and consumption have increased rapidly in recent decades, with harmful effects on the environment and public health as well as on the economy, according to research done by the institute’s Nourishing the Planet project.

“Worldwide meat production has tripled over the last four decades and increased 20% in just the last 10 years,” it said. “Meanwhile, industrial countries are consuming growing amounts of meat, nearly double the quantity than in developing countries.”

A huge volume of water is also used in aquaculture or fish farming. “Fish farming is more advantageous than raising livestock. “For every kilogram of dry feed, we get one kilogram of fish meat,” said Dr. Uwe Lohmeyer of the Deutsche Gesselschaft fur Technische Zusammernarbeit (GTZ), a German Technical Cooperation. “This is far more favorable rate than in the case of say, pigs: to produce the same quantity of pork, a farmer – given the same quality of inputs – has to provide three kilograms of feed.”

It goes without saying that water is indeed the world’s most important resource. “We’re surrounded by a hidden world of water,” pointed out Stephen Leahy, a Canadian journalist, and author. “Liters and liters of it are consumed by everything we eat and everything we use and buy.”

That’s what he calls a “water footprint.” In his book, aptly entitled “Your Water Footprint,” he defines it as the amount of water ‘consumed’ to make, grow or produce something. “I use the word consumed to make it clear this is water that can no longer be used for anything else,” he explained.

According to him, one of the biggest surprises (while writing the book) was learning how little direct use of water for drinking, cooking, and showering is by comparison. For instance, he found out that flushing toilets are the biggest water daily use – not showers.

While low-flow showerheads and toilets are great water savers, the water footprint concept can lead to even bigger reductions in water consumption.

“For example, green fuels may not be so green from a water consumption perspective,” Leahy wrote. “Biodiesel made from soybeans has an enormous water footprint, averaging more than 11,000 liters per liter of biodiesel. And this doesn’t include the large amounts of water needed for processing. Why so much water? Green plants aren’t ‘energy-dense,’ so it takes a lot of soy to make the fuel.”

Beef also has a big footprint, over 11,000 liters for a kilo, according to Leahy. “If a family of four served chicken instead of beef they’d reduce their water use by an astonishing 900,000 liters a year. That’s enough to fill an Olympic size pool to a depth of two feet.”

“Water isn’t just a commodity. It is a source of life,” says Sandra Postel, director of the Massachusetts-based Global Water Policy Project. Postel believes water problems will trail climate change as a threat to the human future. “Although the two are related, water has no substitutes,” she explains. “We can transition away from coal and oil to solar, wind and other renewable energy sources. But there is no transitioning away from water to something else.”

Water covers over 70 percent of the earth’s surface and is a major force in controlling the climate by storing vast quantities of heat. About 97.5 percent of all water is found in the ocean, and only the remaining 2.5 percent is considered freshwater. Unfortunately, 99.7 percent of that freshwater is unavailable, trapped in glaciers, ice sheets, and mountainous areas.

Water is drawn in two fundamental ways: from wells, tapping underground sources of water called aquifers, or from surface flows – that is, from lakes, rivers, and man-made reservoirs. Water is drawn in two fundamental ways: from wells, tapping underground sources of water called aquifers, or from surface flows – that is, from lakes, rivers, and man-made reservoirs.

“World demand for water doubles every 21 years, but the volume available is the same as it was in the Roman times,” observes Sir Crispin Tickell, former British ambassador to the United Nations and one of the organizers of the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. “Something has got to give.”

Again, here’s a thought-provoking statement from Brown: “The most important thing we can do to cope with water scarcity is to use water more efficiently in agriculture. Beyond this, urban recycling of water, still in its early stages, will be one of the keys in dealing with fst-spreading water shortages.”