Text by Henrylito D. Tacio

Photos from Wikipedia

Just like a thief of the night, earthquakes happen anytime, anywhere. And the Philippines is now ripe for another “Big One,” a hypothetical earthquake of 7.2-magnitude or greater. But most Filipinos don’t seem to mind it at all – until it happens.

One of the largest earthquakes that hit the country happened in Gabaldon, Nueva Ecija, in 1645, which spans 100 kilometers long. Official records showed that it generated a 7.9-magnitude earthquake and destroyed the Manila Cathedral as described by its historical marker.

The Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (Phivolcs) says any active faults that have not generated any historical surface-rupturing events have higher potential to generate “The Big One.” A large quake can significantly affect the region and surrounding areas where it happens.

Because of the country’s geographical location, earthquakes happen every now and then.

“Long before Filipinos settled in this country, earthquake faults were already in place,” writes Dr. Alfredo Mahar Lagmay, a professor at the National Institute of Geological Sciences of the University of the Philippines. “These faults shaped our mountains, gave birth to volcanoes, and nurtured life with warmth from Mother Earth. They are the reason for our land’s existence, and we just can’t make them disappear.”

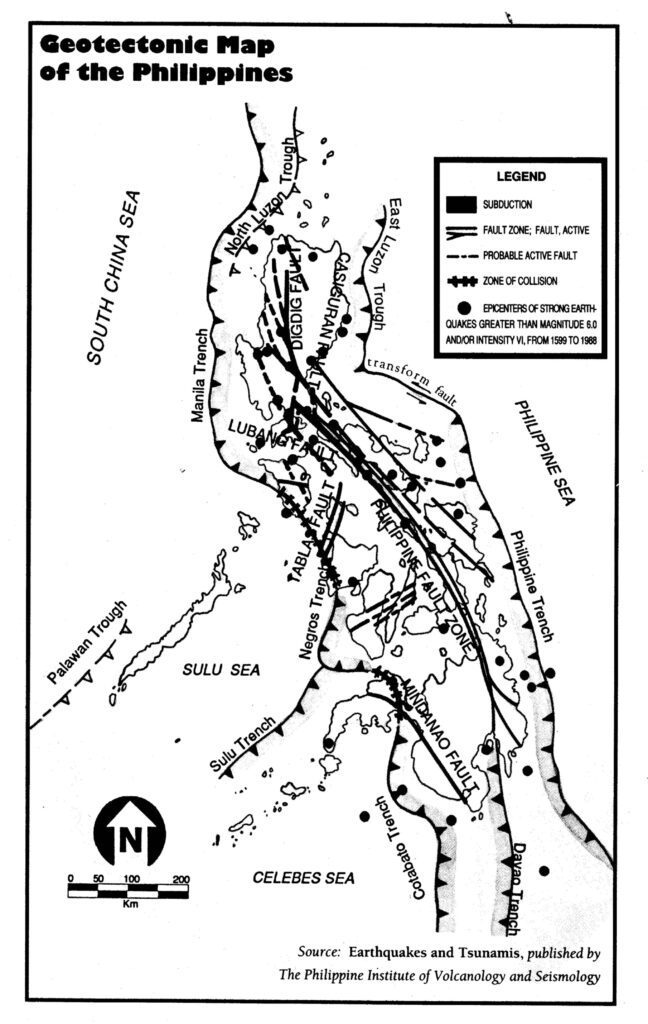

The Department of Science and Technology (DOST) says three tectonic plates encircle the country: the Philippine Plate in the East; the Eurasian Plate in the West; and the Indo-Australian Plate in the South.

“The existence of several fault lines across the country is a manifestation of the movements of these tectonic plates,” DOST states. Geologists define fault lines as slip-ups or cracks in a volume of rock due to rock-mass movement.

A large fault within the earth’s crust is the result of the movement of tectonic plates. A rapid movement of a fault line may produce powerful energy that can trigger a very strong earthquake, scientists say.

The country has five active fault lines: the Western Philippine Fault, the Eastern Philippine Fault; the South of Mindanao Fault; the Central Philippine Fault; and the West or Marikina Valley Fault.

Each year, about 6,000 earthquakes are detected throughout the world. That’s according to Grolier Encyclopedia. Of the total, 5,500 are either too small or too far from populated areas to be felt directly. Another 450 are felt but cause no damage, and 35 cause only minor damage. The remaining 15, however, exact a great toll in death and suffering, besides heavily damaging houses, buildings, and other structures.

Earthquake in Bohol (Photo from Wikipedia)

Geotectonic map of the Philippines

Tsunami after an earthquake (Photo from Wikipedia)

In the Philippines, at least five earthquakes per day occur, Phivolcs reports. “Most are small and harmless,” Dr. Lagmay claims. “It’s the really big and shattering shakes that we need to learn to live with. Though they happen decades apart, the result is always catastrophic.”

For almost four decades now, the country has been affected by ten earthquakes with magnitudes greater than 7.0. As such, the possibility of these destructive earthquakes occurring again “is very strong.”

Most people fear earthquakes because they don’t only destroy buildings and other facilities; they also kill people. But “people can’t be shaken to death by an earthquake,” says Dr. Lagmay.

What kills people are these seven hazards: ground rupture, ground shaking, land subsidence, liquefaction, tsunamis, landslides, and fire. “The quake takes its toll when buildings and infrastructure topple down, when mountains tumble, and when the ground and water bodies heave,” Dr. Lagmay reminds.

On ground rupture, Dr. Lagmay says: “Any structure that sits directly on top of a fault can be seriously damaged when the fault moves. For this reason, no buildings are allowed within the 5-meter buffer zone from an active fault.”

Apart from ground rupture, intense ground shaking may happen away from the fault and cause buildings to topple if not built to withstand the sudden movement of the ground during an earthquake. “This hazard phenomenon is the most destructive of all the earthquake hazards,” Dr. Lagmay says.

Intense ground shaking, according to Dr. Lagmay, can cause land subsidence, making the ground elevation lower than it used to be.

“In flood plains and in coastal areas, the ground can liquefy if water in between sand and gravel mixes, turning land into slurry,” the visiting scientist at the Geophysics Department of Stanford University says. “If not firmly rooted in the ground, buildings on top of the liquefied material may tilt or collapse.”

Tsunami, a Japanese term which means “harbor wave,” happens when large ocean waves are produced when faults shift vertically. “The seismic event displaces the mass of ocean water and creates a train of waves that travel as fast as a jumbo jet toward coastal areas,” Dr. Lagmay says.

When the earth shakes, unstable mountains can fall apart and generate landslides. “Some landslides are small, scarring only the beauty of mountains. But the really big ones can travel from 2 up to 120 kilometers down slope ravaging everything in its path,” Dr. Lagmay says.

There are some reports that Metro Manila is apt for another big earthquake. Emmanuel De Guzman, United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction advisor for Asia-Pacific, admitted that he was unsure when the catastrophic disaster would strike. Still, it is most likely to happen in the thickly-populated metropolis.

“The big earthquake is certainly coming. The question is when? No one can tell. It can happen today, tomorrow, or next year. But certainly, there will be an earthquake,” De Guzman, who previously worked with the Office of Civil Defense of the National Disaster Coordinating Council, was quoted as saying by Philippine Daily Inquirer.

A study done by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) said Metro Manila is not ready to deal with a 7.2-magnitude earthquake in terms of existing resources and given old building structures around and within the metropolis.

The 2002-2004 “Study for Earthquake Impact Reduction for Metropolitan Manila” said that a 7.2-magnitude earthquake triggered by West Valley Fault could kill around 34,000 people, injure some 114,000 persons, partly damage an estimated 340,000 residential structures and cause the collapse of about 170,000 houses.

“Fire will break out and burn approximately 1,710 hectares and a total of 18,000 additional people will be killed by this secondary disaster,” the stud said, adding that infrastructure and lifelines will suffer heavy damage as well.

But it’s not only Metro Manila that will experience the “Big One.” In fact, every region or province in the country is vulnerable to its own “Big One,” reminds Phivolcs. This includes Davao Region.

The region is not spared from the destruction of a huge earthquake that may be triggered by the Surigao-Mati fault, which stretches from Surigao City to Mati Distance – a distance of 320 kilometers.

“A big earthquake as strong as, if not even stronger than, the so-called ‘Big One’ that Metro Manilans are preparing for is a possibility in Davao City in the immediate future,” wrote Antonio M. Ajero, editor-in-chief of EDGE Davao, who attended a press briefing that was convened by the Philippine Information Agency.

Historical records showed a 7.2-magnitude earthquake hit Compostela Valley in 1893. On April 15, 1924, another earthquake with 8.3-magnitude happened somewhere in Sigaboy, now known as Governor Generoso in Davao Oriental.

According to the Phivolcs official, an earthquake with an intensity of 7.2 that happened in Compostela Valley will immediately be felt in Davao City “within less than a minute,” and the magnitude will be about 7.

Recently, Phivolcs came up with ten intensity scales of earthquakes. The intensity scale, which is a measure of how an earthquake is felt in a certain locality or area, is “based on relative effect to people, structure, and objects in the surroundings.”

I. Scarcely perceptible: It is perceptible to people under favorable circumstances. Delicately-balanced objects are disturbed slightly. Still water in containers oscillates slightly.

II. Slight felt: It is felt by few individuals at rest indoors. Hanging objects swing slightly. Still water in containers oscillates slightly.

III. Weak: It is felt by people indoors, especially on the upper floors of buildings. The vibration feels like the passing of a light truck. Dizziness and nausea are experienced by some people. Hanging objects swing moderately. Still water in containers oscillates moderately.

IV. Moderately strong: It is felt generally by people indoors and some people outdoors. Light sleepers are awakened. The vibration feels like the passing of a heavy truck. Hanging objects swing considerably. Dinner plates, glasses, windows, and doors rattle. Floors and walls of wood-framed buildings creak. Standing motor cars may rock slightly.

V. Strong: Generally felt by most people indoors and outdoors. Many sleeping people awakened. Some are frightened; some run outdoors. Strong shaking and rocking are felt throughout the building. Hanging objects swing violently. Dining utensils clatter and clink; some are broken. Small, light, and unstable objects may fall or overturn. Liquids spill from filled open containers. Standing vehicles rock noticeably. Shaking of leaves and twigs of trees is noticeable.

VI. Very strong: Many people are frightened, many run outdoors. Some people lose their balance. Motorists feel like driving with flat tires. Heavy objects and furniture move or may be shifted. Small church bells may ring. Wall plaster may crack. Very old or poorly built houses and man-made structures are slightly damaged, though well-built structures are not affected. Limited rockfalls and rolling boulders occur in hilly to mountainous areas and escarpments. Trees are noticeably shaken.

VII. Destructive: Most people are frightened and run outdoors. People find it difficult to stand on the upper floors. Heavy objects and furniture overturn or topple. Big church bells may ring. Old or poorly-built structures suffer considerable damage. Some well-built structures are slightly damaged. Some cracks may appear on dikes, fish ponds, road surfaces, or concrete hollow block walls. Limited liquefaction, lateral spreading, and landslides are observed. Trees are shaken strongly.

VIII. Very destructive: People are panicky. People find it difficult to stand even outdoors. Many well-built buildings are considerably damaged. Concrete dikes and foundations of bridges are destroyed by ground settling or toppling. Railway tracks are bent or broken. Tombstones may be displaced, twisted, or overturned. Utility posts, towers, and monuments may tilt or topple. Water and sewer pipes may be bent, twisted, or broken.

Liquefaction and lateral spreading cause man-made structures to sink, tilt or topple. Numerous landslides and rockfalls occur in mountainous and hilly areas. Boulders are thrown out from their positions, particularly near the epicenter. Fissures and fault rupture may be observed. Trees are violently shaken. Water splashes or slops over dikes or banks of rivers.

IX. Devastating: People are forcibly thrown to the ground. Many people cry and shake with fear. Most buildings are totally damaged. Bridges and elevated concrete structures are toppled or destroyed. Numerous utility posts, towers, and monuments are tilted, toppled, or broken. Water and sewer pipes are bent, twisted, or broken.

Landslides and liquefaction with lateral spreading and sand boils are widespread. The ground is distorted into undulations. Trees are shaken very violently, with some toppled or broken. Boulders are commonly thrown out. River water splashes violently or slops over dikes and banks.

X. Completely devastating: Practically all man-made structures are destroyed. Massive landslides and liquefaction, large-scale subsidence and uplifting of landforms, and many ground fissures are observed. Changes in river courses and destructive seiches in lakes occur. Many trees are toppled, broken, or uprooted.

“The only way to avoid disasters caused by earthquakes is to prepare for them,” wrote Maria Elena Paterno in her book Earthquake!

DOST urges Filipinos to practice disaster imagination or foreseeing what might happen before it happens. “This is not pure imagination but a large chunk of it is guided by science, engineering, and experience,” DOST explains. “Predicting what could possibly occur will definitely help the people address future problems that they might encounter during the actual disaster.”

Disaster imagination is not only true for earthquakes but also for other large-scale natural disasters. “The amount of preparation needed must be at par or beyond with the degree of severity of the disaster,” DOST points out. “One cannot fall short on preparation especially if survival is at stake.”