Text and Photos by Henrylito D. Tacio

Additional photos courtesy of NOAA

“Rising greenhouse gases in the atmosphere are causing global temperatures to rise, which is leading to the melting of the polar ice caps, which in turn has resulted in rising sea levels and a host of ecological issues,” wrote Alex Renton in a cover story for Newsweek some years back.

“It’s also causing the chemical makeup of the world’s oceans to change so rapidly. Carbon dioxide, one of the key perpetrators in the lineup of man-made greenhouse gases, is absorbed by seawater, causing a chemical reaction near the ocean surface that results in lowered pH levels,” Renton further wrote.

What most people don’t know is that about one-third of all the human-made carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere ends up absorbed by the oceans. This was discussed during the 11th International Coral Reef Symposium (ICRS) held in Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

“Tropical coral reef waters are already significantly warmer than they were and the rate of warming is accelerating,” said Janice Lough of the Australian Institute of Marine Science during the 12th ICRS held in Cairns, Australia. “With or without drastic curtailment of greenhouse gas emissions we are facing, for the foreseeable future, changes in the physical environment of present-day coral reefs.”

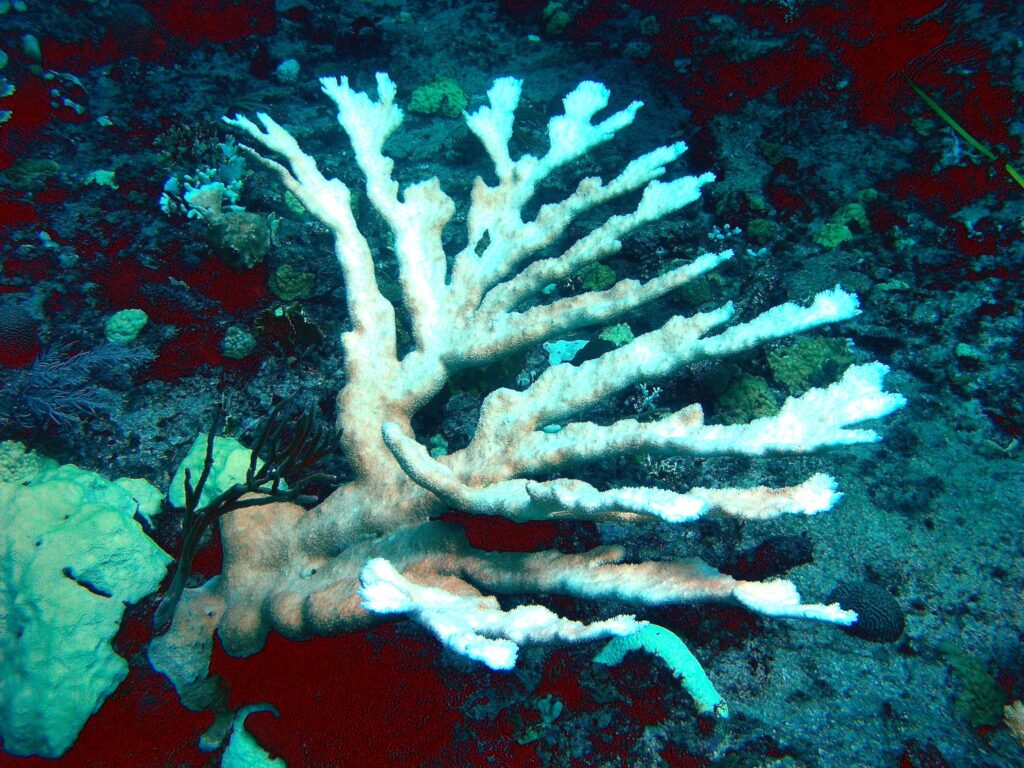

Coral bleaching has been cited as one of the consequences of rising baseline temperatures in the oceans. But what most marine scientists around the world are concerned about most is ocean acidification, which is considered “climate change’s evil twin.”

“Carbon dioxide in the atmosphere eventually finds its way to and dissolves in the oceans, causing the water to become ‘acidic’… reducing the ability of the coral reefs to deposit calcium carbonate or calcify,” explained the late Dr. Edgardo Gomez, who was the founding director of the University of the Philippines Marine Science Institute.

About 25-50% of the carbon dioxide emitted over the industrial period had been absorbed by the world’s oceans, preventing atmospheric carbon dioxide build-up from worsening.

But this atmospheric benefit comes at a considerable price. “As a result, the sea water becomes more acidic and the concentration of carbonate ions decreases,” explains Forest Rohwer, author of Coral Reefs in the Microbial Seas. “Carbonate ions are required by corals, crustose coralline algae, and other marine organisms for building their skeletons and shells. The increasing ocean acidification that lies ahead will affect even the most remote coral reef ecosystems.”

Experts claim the average pH (the concentration of hydrogen ions in a solution) of the ocean has already decreased about 0.1 pH unit from pre-industrial values, a shift that corresponds to a 30 percent increase in the concentration of hydrogen ions and a decrease in carbonate ions. “This has decreased the rate at which reef-building corals build their skeletons (their rate of calcification) by 20 percent,” Rohwer writes.

Ocean pH is projected to decrease another 0.3 to 0.4 pH units by the end of this century. This much change in pH is predicted to reduce coral calcification rates to 40-60 percent of normal. “This is a momentous change,” Rohwer notes.

“Imagine dripping hydrochloric acid onto chalk,” says André Freiwald of the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, one of the authors of a study that appeared in the professional journal Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. “The chalk would disintegrate immediately; the corals could face a similar fate.”

Will it happen soon? “Two hundred years ago, the amount of carbon dioxide in the ocean was around 200 ppm (parts per million). Now it is nearly 400 ppm. If people continue their business as usual, the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change… predicts that it will be more than 500 ppm at the end of the century,” said Dr. Gomez, who was then the chair of the World Bank Coral Reef Targeted Research and Capacity Building for Management Program.

The acidification, Dr. Gomez added, maybe gradual but would happen simultaneously all over the world. He warned that it would be worse than the acidification of agricultural lands due to the use of chemical fertilizers. “Land is more manageable. With the use of organic fertilizer and chemicals, land can easily recover. But once the ocean becomes acidic, it would take millions of years to bring back their natural (state).”

The current acidification may be worse than during four major mass extinctions in history when natural pulses of carbon from asteroid impacts and volcanic eruptions caused global temperatures to soar, according to a study that appeared in the journal Science.

The international team of researchers from the United States, Great Britain, Spain, Germany, and the Netherlands examined hundreds of paleoceanographic studies, including fossils wedged in seafloor sediment from millions of years ago. They found only one time in history that came close to what scientists see today in terms of ocean life die-off – a mysterious period known as the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum about 56 million years ago.

“We know that life during past ocean acidification events was not wiped out – new species evolved to replace those that died off,” wrote lead author Dr. Barbel Honisch, a paleoceanographer at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. “But if industrial carbon emissions continue at the current pace, we may lose organisms we care about – coral reefs, oysters, salmon.”

Dr. Honisch and colleagues said the current rate of ocean acidification is at least 10 times faster than it was 56 million years ago. “The geological record suggests that the current acidification is potentially unparalleled in at least the last 300 million years of Earth history, and raises the possibility that we are entering an unknown territory of marine ecosystem change,” said co-author Dr. Andy Ridgwell of Bristol University.

In the Newsweek article, Renton quoted Callum Roberts, a professor of marine conservation at the University of York, England: “There’s a profound game-changing event going on in the life of the sea. The fact is that changes in alkalinity are going to cause massive reorganization of marine life, impacts on marine food webs, productivity, all sorts of things. We’re heading for a car crash here.”