Rice straw clean fuel is gaining attention as an innovative solution that transforms agricultural waste into a sustainable energy source in the Philippines.

Planting rice is never fun, so goes a line from a popular folk song. Despite this, a significant number of Filipinos remain engaged in rice production.

Statistics indicate that there are 2.9 million Filipinos involved in rice farming and related activities within the country. Rice cultivation occurs over approximately 4.8 million hectares, of which 3.28 million hectares are irrigated, while the remaining 1.51 million hectares consist of non-irrigated areas, including rainfed and upland regions, according to the Philippine Statistics Authority.

The Philippines is estimated to generate between 11 to 12 million tons of rice straw each year, although some reports suggest that the figure could reach as high as 15.2 million tons of rice straw waste, derived from an annual rice production exceeding 15.2 million tons.

Unfortunately, Filipino farmers view rice straw as waste due to its minimal or nonexistent commercial value. Consequently, most of it is burned. “Burning of rice straws, generally practiced during the harvest season, causes air pollutants such as carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxide, and sulphur dioxide,” said the Philippine Rice Research Institute (PhilRice).

The practice of burning waste straw in rice fields is not environmentally sustainable, as it renders the soil infertile by depleting essential nutrients. According to PhilRice, burning reduces the soil’s nitrogen content, diminishes phosphorus by 25%, potassium by 20%, and sulfur by 5-60%.

In addition, some beneficial insects are most likely to be killed when rice straws are burned in the open field. “Useful insects kill some harmful insects which destroy palay and make production less,” said Evelyn Javier, supervising science research specialist of PhilRice’s Agronomy, Soil and Physiology division.

More importantly, burning rice straw is bad for your health. “Rice straw burning is also known to emit particulate matter and other chemicals such as dioxins and furans that have negative impact on human health,” said a policy brief paper published by the Economy and Environment Program for Southeast Asia (EEPSEA).

If rice straw is allowed to decompose in the fields, methane emissions are anticipated. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas, over 80 times more harmful than carbon dioxide. Greenhouse gases are those present in the atmosphere that trap heat, leading to an increase in the surface temperature of celestial bodies, including Earth.

“An estimated 19 percent of the world’s methane production comes from rice paddies,” admits Dr. Alan Teramura, a botany professor at the University of Maryland. “As populations increase in rice-growing areas, more rice – and more methane – are produced.”

Turning rice straw into something useful is very challenging. That’s what Dr. Craig Jamieson, a British national who’s originally trained in horticulture and has a master’s degree in International Rural Development with “Distinction.”

His work has taken him across Africa and Asia developing bioenergy solutions that enhance rather than compete with food production. In 2016, with support from the United Kingdom government, Craig established an industrial pilot plant making clean fuel from waste rice straw. Straw Innovations (SI) Ltd. was born.

He collaborated with the Laguna-based Southeast Asian Regional Center for Graduate Study and Research in Agriculture (SEARCA) to create a pilot facility that produces clean fuel from rice straw.

The Rice Straw Bioenergy Hub (RSBH), as it is called, facilitates access to clean energy for remote and underserved rural communities. The biogas produced, derived from waste rice straw, offers an innovative suite of technological services for rice farmers.

“The RSBH stands as a testament to what we can achieve when science, innovation and community come together,” Dr. Jamieson pointed out.

The clean fuel produced from RSBH is utilized for drying grains and subsequent milling. “We consulted with farmers, and they expressed a preference for using the energy for productive activities rather than for domestic purposes. Therefore, that is our focus,” Dr. Jamieson clarified.

After harvesting, drying the palay is the next most crucial process. Upon harvesting, rice can contain as much as 25% moisture, according to IRRI. The objective of rice drying is to lower its moisture content to the recommended levels suitable for sale and long-term storage.

“It is important to dry rice grain as soon as possible after harvesting – ideally within 24 hours,” IRRI explained. “Delays in drying, incomplete drying or ineffective drying will reduce grain quality and result in losses.”

However, before drying can occur, rice must first be harvested. In this context, the SI is introducing a rice harvesting system that has been developed over a span of five years. “The primary challenges involve removing the rice straw from the field and transporting it to a location where it can be utilized,” Dr. Jamieson said.

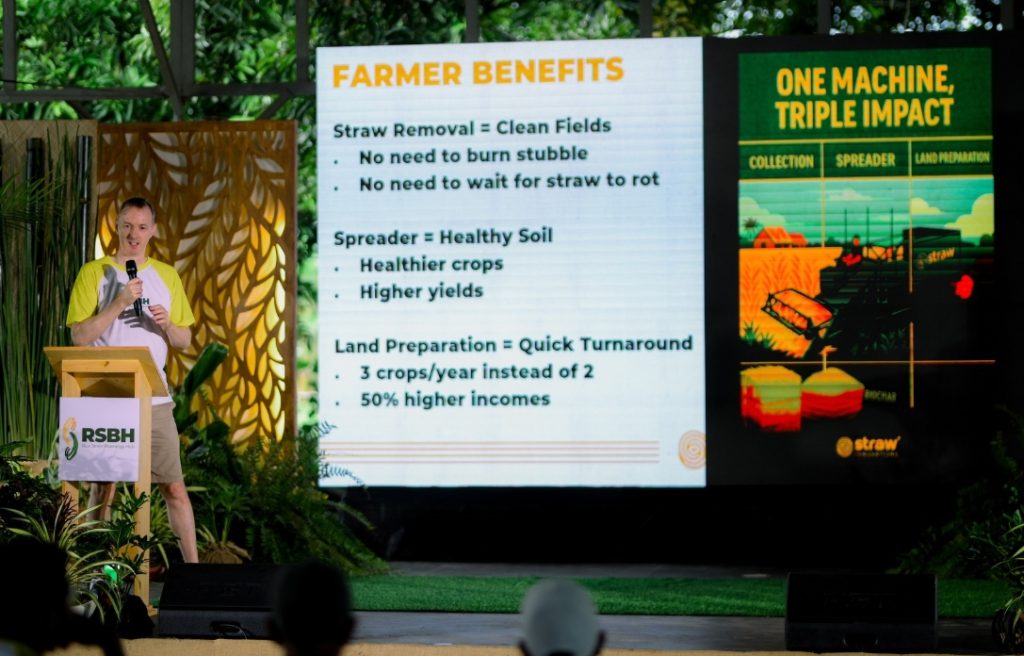

The solution is the “5-in-1” harvesting technology, which refers to a machine that is claimed to be the first of its kind globally.

“Our machine operates in a single pass across the field and executes the five distinct operations involved in conventional straw collection – harvester, chopper, rake, densifier, and collection. It is more efficient and, importantly, it functions effectively even in wet conditions (muddy or flooded fields),” he emphasized.

The harvested palay is subsequently transported to a different machine where the grain is separated from the rice straw. “At the biogas hub, a dryer utilizes energy derived from rice waste to dry the rice grain, while another machine removes the husk, and yet another mills the grain, resulting in the final product,” said Dr. Jamieson.

The drying process takes approximately 12 hours. “The innovative technology involves using rice straw to fuel the entire process,” he explained. “We provide farmers with the opportunity to maintain ownership of their grains throughout the entire procedure.”

In many current scenarios, farmers receive only 4% of the rice’s purchase price. In the SI approach, farmers can take advantage of its harvesting, drying, and milling services, and subsequently sell the finished products to consumers. “We simply take our share after the sale,” he said.

To generate methane at the hub, water is mixed with the rice straw. The methane gas serves as a direct alternative to diesel or kerosene in traditional dryers.

“In the past, the government tried to give out free rice dryers but as soon as something broke, the dryers were no longer used,” Jamieson said. “Our business model is to operate our equipment and offer it as a service to farmers. They pay us a service fee but don’t need to buy or operate our equipment.”

Dr. Jamieson asserted that effective management of rice straw in a sustainable manner must achieve a balance between energy production and soil restoration to preserve soil fertility and guarantee productive agricultural lands.

“Some of the bioenergy we are producing is, in fact, combined heat and biochar,” he said. “The heat is used for drying rice, and the biochar is returned to the soil to build up carbon levels and increase fertility. We are encouraged by the early results of this approach as a solution for the food-energy-water-carbon nexus.”

The Department of Agriculture (DA) Region IV-A recognized the initiative for its potential benefits to farmers and the economy. During the Techno-Demo at Pila, Laguna, DA Regional Director was quoted as saying:

“Rice straw innovation can power a circular agricultural economy—a system where nothing is wasted and every byproduct adds value. When we treat straw as a resource, we create farming that delivers higher yields, cleaner air, stronger rural economies, and a healthier planet.”

At the Techno-Demo, SI also showcased a full suite of sustainable rice farming technologies and innovations. These include:

· Straw Traktor. This is a machine equipped with a soil amendment applicator and a land rotavator, leading to improved soil health, enhanced crop quality, and increased yields.

He said processed rice straw can be transformed into pellets that can be utilized for the production of biogas and biochar (a substance resembling charcoal), which are currently being employed by various companies.

Rice straw can also be used as bedding for livestock, organic compost or fertilizer, and even as a substrate for mushroom cultivation—thereby generating new income opportunities for farmers.

· Mushroom cultivation. This process transforms rice straw into a source of nutritious food and additional income for farmers.

· Improved rock weathering. This advancement utilizes natural soil amendments to enhance fertility and facilitate carbon sequestration.

· Koolmill. A rice milling technology that is energy-efficient and produces less waste.

The British innovator is confident that the rice straw bioenergy technology can eliminate the burning of millions of tons of rice straw waste throughout Asia, where the majority of rice is cultivated. “It can provide clean energy access to the 150 million small-scale rice farmers who require it to process their crops and create new income opportunities,” he said.

Dr. Jamieson hopes it can address energy challenges faced by developing countries like the Philippines. “As a bioenergy specialist, the potential of rice straw made me drool,” he said. “All around the world, the hunt has been on for a large amount of biomass that can be used for delivering clean energy without competing with anything else.”

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter