Text and Photos by Henrylito D. Tacio

Visitors, both foreigners, and locals, who come to Davao City for the first time almost always include the Philippine Eagle Center in Malagos, Calinan District as one of their itineraries. Some 30 kilometers northwest and about an hour’s drive from downtown Davao, the center is home to the endangered Philippine eagle (Pithecophaga jefferyi).

The center is managed by the Philippine Eagle Foundation (PEF), the prime mover in eagle conservation, breeding, rehabilitation, and education in the country. Almost three dozens of eagles can be found at the center.

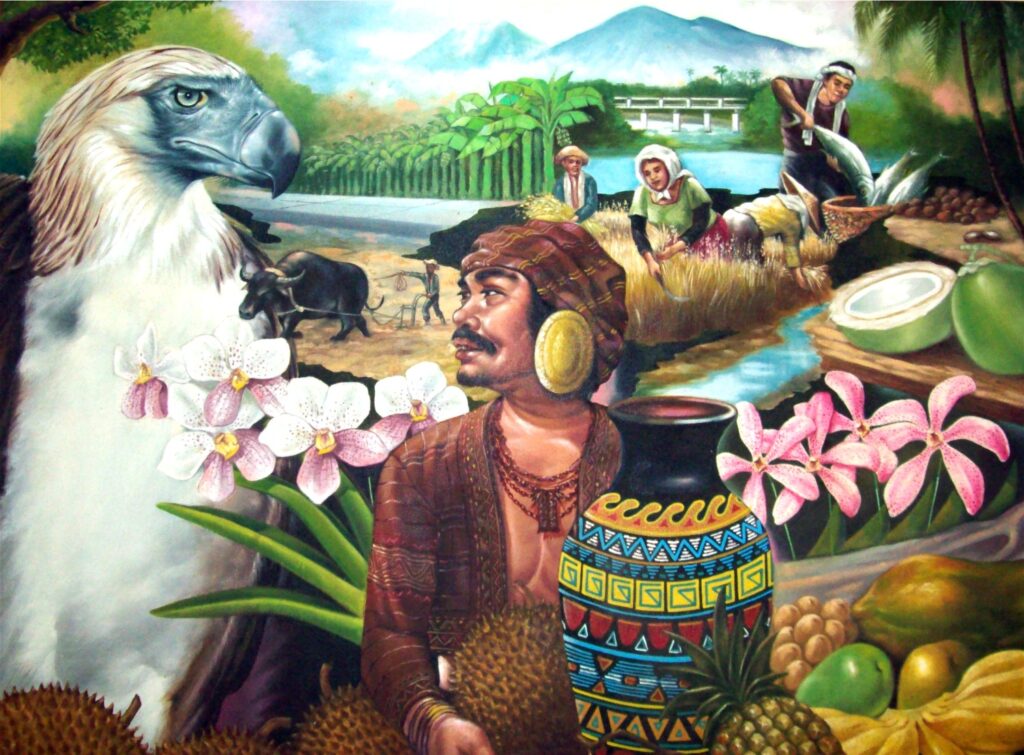

“The great Philippine eagle is not only our flagship species for wildlife conservation but also the best indicator of the forest ecosystem’s health,” said Dennis Joseph I. Salvador, the PEF’s executive director.

According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, a pair of Philippine eagles need 7,000 to 13,000 hectares of rainforests to survive.

The Philippine eagle is second only to the Madagascar sea eagle in rarity. In size, it beats the American bald eagle; it is the world’s second-largest – after the Harpy eagle of Central and South America.

The eagle was being collected in the country as early as 1703, but it was not until 1896 that it was “discovered” in Samar by the English naturalist, John Whitehead, who called it the “Great Philippine eagle.”

Before it was called the Philippine eagle, it was known as the monkey-eating eagle (its generic name, Pithecophaga, comes from the Greek words pithekos or monkey, and phagein, meaning eater). However, it was found out that monkeys actually comprised an insignificant portion of its diet, which consists mainly of flying lemurs, civet cats, bats, rodents, and snakes. On May 8, 1978, through Presidential Proclamation No. 1732, the eagle was finally given its present name.

With a span of nearly seven feet and a top speed of 80 kilometers per hour, the Philippine eagle can gracefully swoop down on an unsuspecting “victim” and carry it off without breaking flight.

If there is such a thing as forever, the Philippine eagles have proven it. “These birds remain loyal to their mates and they bond for life,” the Biodiversity Management Bureau (BMB) says. “Once an eagle reaches sexual maturity – at around five years for female and seven years for male – it is bound for life with its mate,” the PEF adds. “They can be seen soaring in pairs in the skies.”

During the breeding season, the eagle does aerial courtship and mate in the nest or near it. The female eagle lays only one egg every two years. Both parents alternately incubate the egg for about 60 days, although the female spends more time incubating while the male hunts.

Upon hatching, the eagle remains in the nest for about 5.5 months. Once it fledges, the eagle’s parents will continue to look after its young for as long as 17 to 18 months, teaching the young eagle how to fly, hunt, and to survive on its own. The young eagle matures in about six years.

Studies show that the eagle’s nest is approximately 80 feet above the ground (usually on tall trees) in prominent mountain peaks overlooking a river or stream to give a good view of its territory.

In the past, Philippine eagles abounded in the forests of Mount Apo and other parts of Mindanao. They can also be seen flying over in the forests of the Sierra Madre in Luzon and Samar and Leyte in the Visayas.

Today, Philippine eagles inhabit those places, but their number has dwindled. In fact, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources has declared the Philippine eagle as a “critically endangered species.”

This is the reason why the efforts of PEF should be supported by Filipinos. A private, non-profit, non-stock organization, it is dedicated to saving the endangered bird. “The Philippine eagle is the largest predator we have,” Salvador said. “By using the Philippine eagle as the focal point of conservation, we are, in the process, saving wildlife and their habitat.”

According to Salvador, PEF is committed to promoting the survival of the Philippine eagle, “the biodiversity it represents, and the sustainable use of our forest resources for future generations to enjoy.”

The Philippine eagle is found nowhere except in the country. “The Philippine eagle represents a rare product of evolutionary creation,” PEF said on its website. “Based on recent genetic studies, it has no close relatives left among the living species of eagles in the world.”

PEF came into existence in 1979 after the founders of Films and Research for an Endangered Environment (FREE) left the country. FREE was established by Peace Corps volunteers Robert S. Kennedy and Vaughn and Lorenne Rundquist. When they returned to the United States, they created PEF to continue the work they have started.

Primarily a research facility, the Philippine Eagle Center is nestled at the rolling foothills of Mount Apo, the country’s highest peak. Its work, however, is divided into two components: in situ and ex situ conservation. In situ is the raising of birds in their original habitat, while ex-situ is the method of propagating the species in captivity.

PEF now has more than three decades of experience in developing technologies for the captive propagation of Philippine eagles. These include infrastructure design, breeding techniques, incubation and hatching procedures, and the assessment of health and nutrition requirements.

The foundation also has a field operations program involving two components: field research and community-based resources management. Research activities include habitat assessment, prey counts, monitoring of nests in the wild, verifying eagle sightings, and retrieval operations.

“All these are geared towards protecting wild populations and mitigating the impacts of human activities,” Salvador explained, adding that more studies are still needed to effectively manage wild eagle populations.

PEF also has worked closely with the BMB, a line agency of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). Both agencies are working in tandem on captive breeding “to promote a greater understanding of the eagles’ biology, food habits and survival.”

This collaborative effort has open opportunities for research on eagle breeding behaviors “that will substantially increase our understanding of their ecology and biology,” said the BMB on its website.

In 1988, PEF opened its facility to the public as an education center. “The eagle center is probably the biggest tool we have in educating the people,” Salvador said. “The facility enables us to bring the Philippine eagle and other wildlife closer to our people.”

According to Salvador, most of those who visit the eagle center never had the opportunity to see the forest and the animals that live in the forest.

“The eagle center provides our visitors and guests with a small glimpse of that world, a world which they have increasingly become detached from. We make good use of this opportunity to let them know how the forest relates to their own lives – even if they live so far away from it,” Salvador said.

In an article that appeared in National Geographic, Christy Ullrich reported that several steps are currently going in the country to save the Philippine eagle from oblivion. “Certain conservation measures are already in place to help protect the comparatively scant number of surviving eagles. Legislation has been passed to prohibit hunting and protect nests, as well as to survey the birds’ habitat, create public-awareness campaigns, and step up captive breeding.”

But the most significant threat – deforestation – continues. “Habitat loss – due to destruction, fragmentation or degradation of habitat – is the primary threat to the survival of our wildlife,” the BMB pointed out. “When an ecosystem has been dramatically changed by human activities – such as agriculture, oil and gas exploration, a commercial development or water diversion – it may no longer be able to provide the food, water, cover, and places to raise their young.

“Every day, there are fewer places left that wildlife can call home,” it added.

Filipino environmentalists are urging all Filipinos to help save the country’s bird icon from extinction. If only these birds could talk, these would be their plead:

“I have watched forests disappear, rivers dry up, floods ravage the soil, droughts spawn uncontrolled fires, hundreds of my forest friends vanish forever and men leave the land because it was no longer productive. I am witness to the earth becoming arid. I know all life will eventually suffer and die if this onslaught continues.“