Text and Photos by Henrylito D. Tacio

The Philippines – with a land area of 30 million hectares and comprises about 7,107 islands of which only 2,000 are inhabited – has 36,289 kilometers of coastlines (almost twice that of the United States).

It is no wonder why the country has the second-highest number of seagrasses in the world. It has 18 species of seagrasses thriving along its coasts. Only Western Australia, with 30 species, has more than that total.

Most Filipinos don’t know that the Philippines is home to several seaweed species, of which only 893 species have been identified so far. Seaweed is not a seagrass, nor is it a weed; it is actually marine algae.

“(The Philippines has) 197 species in 20 families for green algae, 153 species in 10 families for brown algae, and 543 species in 52 families for red algae,” said Dr. Marco Nemesio Montaño, of the Marine Science Institute of the University of the Philippines-Diliman, during a seminar on Enhancing Marine and Agricultural Products through Biotechnology some years back.

Seaweeds come in several forms, shapes, and colors. Of over 9,000 species of seaweeds found worldwide, red tops with 6,000 species, followed by brown (2,000 species) and finally green (1,200 species).

In the Philippines, seaweeds are economically important as a source of carrageenan, an indigestible carbohydrate (polysaccharide) extracted from edible seaweeds. It is used for food and other industrial applications.

The seaweed industry in the country started in the mid-1960s. However, the first commercial seaweed farming was introduced in Sulu in Sulu Seas in the early 1970s. The Philippines is one of the few countries in the world that pioneered the farming of these plants in substantial quantities, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

This recognition placed the country on the seaweed map until 2008, when it was overtaken by Indonesia. The Seaweed Industry Association of the Philippines said the country used to provide 70% of the worldwide raw material supply. Today, it is down to 40%.

The decline in production is attributed to:

- Decreasing quality of farmed cultivars or seedstocks.

- Unavailability of seedstocks due to typhoons, an outbreak of diseases.

- Decreasing carrying capacity of farms.

- Non-compliance with product specifications set by the international trade for carrageenan.

- Lack of new products to improve the competitiveness of the processing industry.

But there’s good news. The Laguna-based Philippine Council for Agriculture, Aquatic and Natural Resources Research and Development (PCAARRD) has identified seaweed production as one of those industries with a brighter future.

“Seaweed farming is recently the most productive form of livelihood among the coastal communities in the country,” PCAARRD. “It is one of the most productive and environment-friendly aquaculture systems in the Philippines.”

Of the 200,000 hectares of shallow marine waters available for seaweed production, only 60,000 hectares are being used. “About 200,000 families are employed, producing around 90,000 to 100,000 metric tons of dried Eucheuma seaweed alone.”

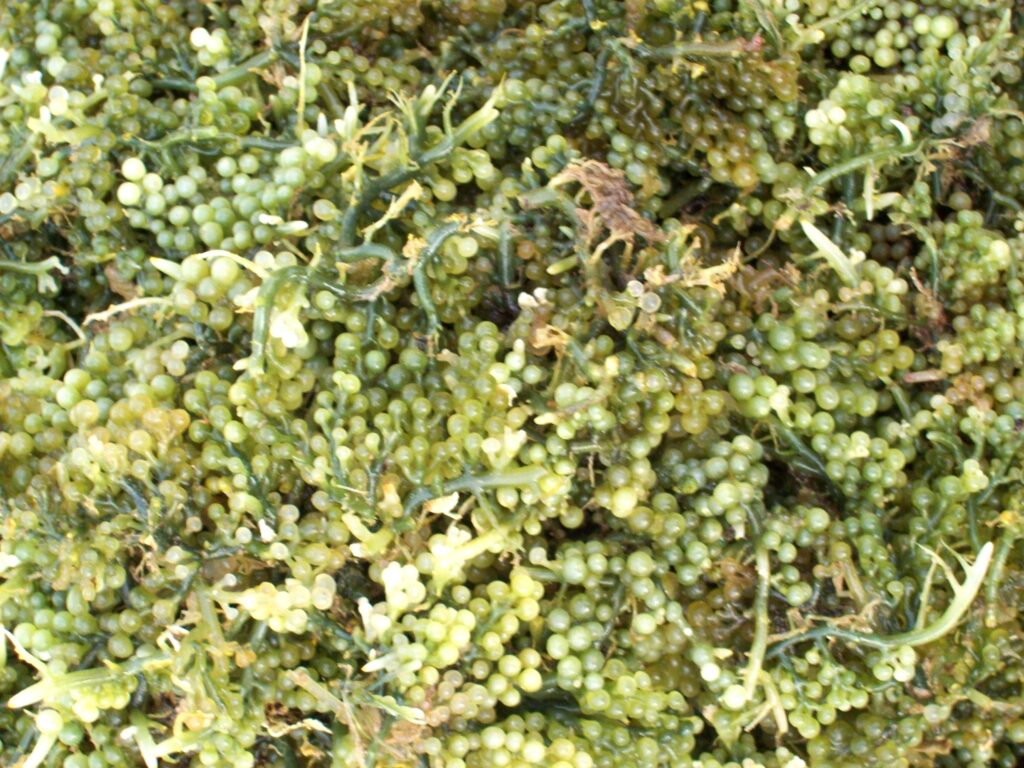

Locally known as guso, Eucheuma (scientific name: Kappaphycus alverezil) comes in various colors: brown, red, or green. This is the species used in the production of carrageenan.

Aside from Eucheuma, the other commercially available seaweeds in the country, mostly from natural harvests, are Gracilaria, Gelidium, Caulerpa, Sargassum, and Ulva. Growing or farming of these species is also highly feasible in certain locations.

Seaweed is not your ordinary algae. In fact, it is considered a superfood. “Seaweed draws an extraordinary wealth of minerals from the sea that can account for up to 36% of its dry mass,” the PCAARRD states. “This food is high in iodine, magnesium, iron, vitamins A, B, and C, protein, vitamin B, fiber, and alpha linoleic acid, among others.”

Seaweed is also a good source of calcium. Alaria, for instance, is an Atlantic seaweed related to the Japanese wakame, has the most calcium, meeting 14% of the daily value in a one-half cup serving. Arame and hijiki, bot Japanese seaweeds, are also good sources of calcium, meeting 10% of the daily value in a one-half cup serving.

“Calcium is not only important for bone health but also for muscle function, nerve transmission, and hormone secretion,” explains PCAARRD, a line agency of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST). “Seaweed packs super-high amounts of calcium that is higher than broccoli, and almost as rich as legumes in terms of protein.”

Another good thing about seaweed is their fiber content, which is “mostly soluble fiber that turns into a gel, slowing down the digestive process, thus inhibiting the absorption of sugars and cholesterol.”

People living in the uplands could surely benefit from eating seaweed as it is a good source of iodine. “Iodine is one of those micronutrients that are hard to obtain in food,” the PCAARRD stresses. “Commercial table salt often adds iodine to create ‘iodized’ salt. As a good alternative, eating seaweeds can help bolster the lth without population’s thyroid and brain health without adding to much table salt.”

Other seaweed health benefits include improved memory, clear skin, healthy vision and hearing, good dental health, healthy thyroid function, and improved immune system. Seaweed also prevents allergies and infections, lowers blood pressure, nurtures healthy heart vessels, normalizes cholesterol levels, and aids in waste movement and digestion.

As stated earlier, seaweed is economically important in the production of carrageenan. It is used in several preparations as a thickener, binder, emulsifier, and suspending and gelling properties.

Aside from eating seaweeds raw, they are also used in cosmetics, in the production of fertilizers, and for the extraction of industrial gums and chemicals. They have also been seen as a potential source of long and short-chain chemicals with medicinal and industrial uses.

In Asia, seaweed is a popular ingredient in some recipes. China’s zicai, Korea’s gim, and Japan’s nori is actually sheets of dried Porphyra species used in soups or wrap sushi. Chondrus crispus (commonly known as Irish moss or carrageenan moss) is a red alga used in producing various food additives.

“With today’s trend of consumers trying to embrace a healthy lifestyle, munching on these organically and naturally grown food will increase the demand for seaweeds that will benefit the seaweed industry and farmers,” the PCAARRD surmises.

Agriculture in itself can benefit from seaweeds. Some studies found out that when polysaccharide is reduced to tiny sizes by a safe technology process called irradiation, it can be an effective growth promoter and makes rice resistant to major pests.

Carrageenan, as a growth enhancer, offers an array of benefits that result in improved productivity. Used properly as prescribed, it makes the rice stem stronger, thus improving rice resistance to lodging. It also promotes resistance to rice tungro virus and bacterial leaf blight, giving farmers increased harvest.

What is good about this seaweed additive is that it is compatible with the traditional fertilizer application practice, thereby allowing easy acceptance and less resistance from farmers. It also promotes sustainable agriculture since it is environment-friendly and enhances the presence of natural enemies that fight major pests in rice fields. Lastly, it promotes more efficient absorption of plant nutrients that enables improved growth.

In a field trial conducted in Bulacan by the research team using carrageenan, rice yield was significantly increased by 63.6 – 65.4%. This treatment provided higher grain weight (of 450 grams and 455 grams, respectively) compared to traditional farmers’ practice of applying nine (9) bags of fertilizer per hectare that yielded only 275 grams.

Application of six bags of fertilizer per hectare plus 200 parts per million (or 20 milliliters) of carrageenan is more or less comparable with the application of just three bags of fertilizer per hectare with the same mixture.