Text and Photos by Henrylito D. Tacio

You may be now at the top of your career – whether a physician, nurse, administrator, manager, or whatever profession – but the time will come that you will finally bid goodbye to what you love doing.

That’s the time when you are already old (if you won’t die young) and have to retire (when you are given a watch as your retirement present; paradoxically, you don’t need a watch to remind you of your day-to-day activities).

But whether you like it or not, you have to face that day. While there are few who won’t accept such inevitable events in life, there are those who are ready for it. “Finally, I can do what I want to do,” someone quipped.

“Learn the lessons of history,” Mark Singer wrote in The Changing Landscape of Retirement: What You Don’t Know Could Hurt You. “Don’t let how you feel about your tenure at your organization drive you to make poor investment decisions that could potentially derail a successful retirement.”

There are retirees who travel here and there. And there are those who go into what they were longing for before – to go into farming. “When I retire,” said an internist who worked most of his life treating patients, “I want to do what my father used to do – tilling the soil and harvesting the fruits of his labor.”

A doctor, although still in his late 40s, is already growing bananas on the farm that was given by his parents. Another one just retired, goes to his province every weekend to manage the farm he bought a decade ago.

People who are soon to retire and interested in farming can get an idea from the Mindanao Baptist Rural Life Center (MBRLC) Foundation, Inc., a non-government organization based in barangay Kinuskusan in Bansalan, Davao del Sur. It has developed a farming system that integrates crop production with tree farming.

“We call it Sustainable Agroforest Land Technology,” says Jethro P. Adang, the center’s director. SALT 3 is the shorter word for it; actually, it’s a modification of Sloping Agricultural Land Technology (SALT), a sustainable farming system for the uplands.

Stopping erosion

Alley cropping

At least 60% of the country’s total land area of 30 million hectares is classified as uplands. Most of these areas are undergoing some forms of soil erosion. “If the soil on which all agriculture and all human life depends is wasted away, then the battle to free mankind from want cannot be won,” Lord John Boyd Orr once reminded.

The topsoil is “the country’s most precious natural resource.” It is described as “the bridge between the inanimate and the living.” Soil formation is a prolonged process that takes place at the rate of 2.5 centimeters per century. The topsoil, which is rich and fertile because of its organic matter content, is being washed in a matter of seconds by strong rain.

In the Philippines, about a billion cubic meters or about 200,000 hectares of one-meter deep topsoil are lost every year to erosion, according to the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR).

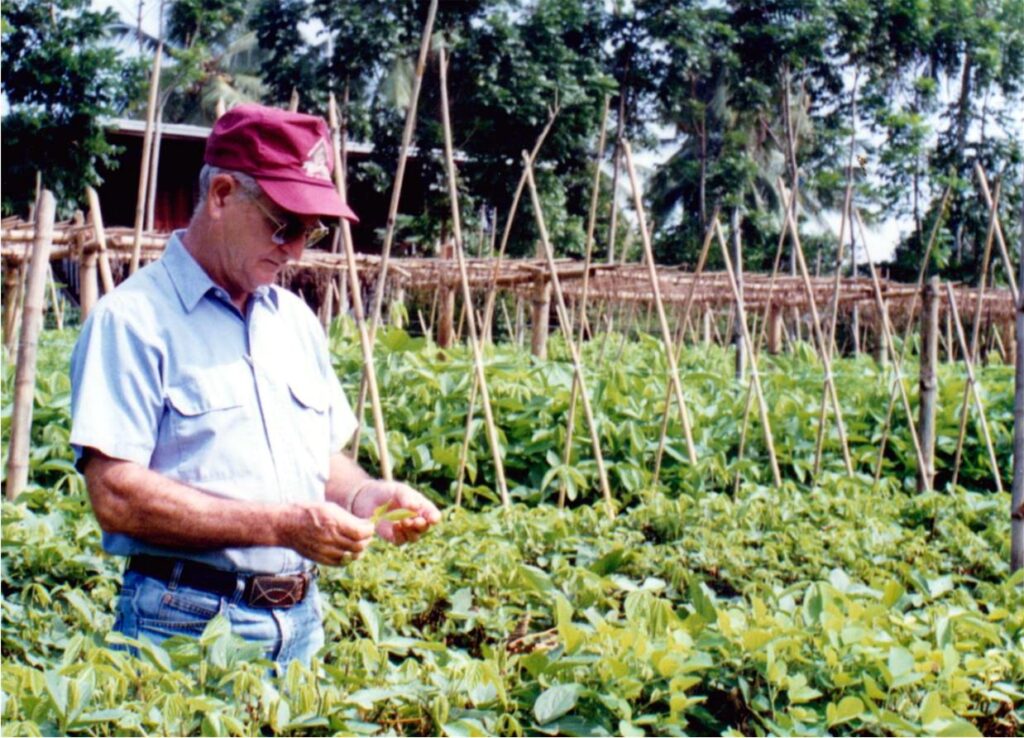

“Soil erosion is an enemy to any nation – far worse than any outside enemy coming into a country and conquering it because it is an enemy you cannot see vividly. It’s a slow creeping enemy that soon possesses the land,” said Harold R. Watson, an American missionary who received the 1985 Ramon Magsaysay Award for peace and international understanding.

Watson was cited for developing SALT and other MBRLC farming schemes. SALT is a packaged technology of soil conservation and food production that integrates several conservation measures in just one sitting.

“Basically, the SALT method involves planting of field and permanent crops in 3-5 meter bands between double-contoured rows of nitrogen fixing shrubs and trees (examples: ipil-ipil, kakawate and introduced species such as Flemingia macrophylla and Desmodium rensonii) to minimize soil erosion,” Adang explains.

Permanent and agricultural crops are planted all over the farm. Permanent crops refer to cacao, coffee, banana, citrus, and fruit trees. Among the recommended crops are vegetables, cereals, and legumes.

In SALT, crop rotation is being implemented. For instance, those strips planted with cereals (corn or upland rice) earlier are planted with peanuts or winged beans in the next cropping. “Crop rotation helps to preserve the regenerative properties of the soil and avoid the problems of infertility typical of traditional agricultural practices,” Adang says.

Multistory cropping may also be practiced (planting black pepper, corn, and lanzones together in one hedge). In waterlogged areas, gabi, kangkong, and other water-loving crops are planted. “We all do these to make use of all the available spaces of the farm,” Adang says.

“Some of the crops should be planted to feed the farmer’s family, while other crops are grown for sale, so family income is well spread out over the season,” says Adang. “Every week or every month, there’s always something to harvest. The system can, in fact, raise the family income threefold.”

But what makes SALT environment-friendly is that it helps in the establishment of a stable ecosystem. The double hedgerows of leguminous shrubs and trees between the land strips where crops are planted help conserve water and soil. The hedgerows, when cut every 30-45 days and incorporated back into the soil, improve its fertility and serve as mulching materials.

(Simple Agro-Livestock Technology or SALT 2 is the integration of goats into the SALT system. Designed for only half a hectare, 12 does are raised together in one house situated in the middle of the farm with one buck living in an adjacent shed.)

SALT is designed for one hectare. An additional one hectare is added in SALT 3, however. One hectare is allotted for crop production while another hectare for trees. The trees are planted in the upper portion, so it can also help minimize the rushing of the water downstream.

It may take some time to establish the crop production area, but in the upper portion, once the trees are planted, they may be left to grow on their own. The farmer may concentrate more of his time on growing crops.

In terms of tree production, Adang talks about “tree time zones” of 1-5, 6-10, 11-15, and 16-20 years, within which progressively more valuable products are harvested. Some very valuable trees could be left longer, which he calls as “the grandchildren project.” As he explains it: “You plant trees not for yourself but for your grandchildren.”

Among the tree species planted in the SALT 3 model farm are bamboo, Sesbania sesban, “ipil-ipil,” Acacia auriculiformis, and A. mangium, Swietenia macrophylla, Pterocarpus indicus (more popularly known as narra), and Samanea saman (rattan is planted below it). Some of these are planted basically for fuelwood, while others are for furniture purposes.

According to Adang, SALT 3 is MBRLC’s contribution to saving the planet earth by curbing the cutting of forests. It has been reported that if the Philippines will not do something drastic now, it would be the first country in Asia to completely lose its forest cover soon. Cebu is a case in point: It has a “zero-forest cover,” said environment officials.

“Most of the country’s once rich forests are gone,” says the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization’s study entitled, “Sustainable Forest Management.”

“We have lost most of our forest of old over the past 50 years and, along with them, many of the ecological services they provide,” deplores Peter Walpole, executive director of the Environmental Science for Social Change.

But the destruction caused by deforestation is already written on the wall. “Deforestation has left upper watersheds unprotected, destabilizing river flows, with significant effects on fish population and agriculture,” wrote Robert Repetto in The Forest for the Trees? Government Policies and the Misuse of Forest Resources.

“The implications for hydroelectric projects and irrigation facilities have already become apparent in Luzon, where anticipated lifetimes of important reservoirs have been cut in half by sedimentation.”

According to Dr. Rodel D. Lasco, a member of the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, deforestation is one of the leading causes of greenhouse gas emissions. “Ten billion to 12 billion tons of carbon dioxide are released per year due to deforestation, that is loss of forest, as well as through agriculture, such as livestock, soil and nutrient management,” he pointed out.

Indeed, by following SALT 3, deforestation can be curtailed. Clarissa Pinkola Estés, author of The Faithful Gardener: A Wise Tale About That Which Can Never Die, reminded: “To be poor and be without trees is to be the most starved human being in the world. To be poor and have trees is to be completely rich in ways that money can never buy.”